From John Fowles with love: how the author’s first true romance and lost poem came to light

In 1951 John Fowles was an assistant teacher at Poitiers University when he fell seriously in love for the first time. More than 60 years on, Mike Abbott meets the student he fell for and uncovers the unpublished poem he wrote for her

John Fowles died 10 years ago. The two volumes of his Journals were published just before and after his death. At the time, they stirred up coverage and debate because they were extraordinarily candid and indiscreet. However, in the past decade the dust has settled and, as is the nature of things, the name of this literary superstar from the 1960s and 70s is now rarely mentioned.

I was recently leafing through the first volume of the Journals and was drawn to Fowles’s description of his relationship with a young French student at Poitiers University, where he was a teaching assistant. It was his first academic post and he was 24 years old. The episode opens on Sunday 7 January 1951:

Sitting about in a cafe most of the day. People bore me profoundly and desperately. There is one girl who is beginning to interest me fractionally. She attacks me all the time, and I attack her, and we’re not bored while we’re doing it.

Thus began an intense six-month romance that clearly made a major impact on the young author. It was his first serious love affair. The student was called Ginette Marcailloux and she was 23 years old. He describes her as a dark vivacious meridional beauty, interesting, intelligent and quick-witted. Soon he was confiding to his journal: “I feel closer to her than anyone else I have everknown.” There is endless sensual kissing and caressing, dancing at the student centre, moonlit walks in the surrounding countryside. “The next stage is bed. She is too virtuous for that.” Fowles devotes more than 70 pages to the detailed description of them growing ever more intimate through the spring. He even begins to contemplate marriage.

Then my eye was caught by a footnote saying that Limoges was Ginette’s hometown. I live in Limoges. On a whim I picked up the phone book to see if there were any Marcailloux listed, although I thought that her maiden name would have since been changed by marriage. My finger ran down the small print … Marat, Maraval, Marbouty … and then stopped. There was only one Marcailloux. And it was Ginette.

It took me a few days to summon up courage to pick up the phone. How do you speak to a lady of 87 about a love affair that took place 64 years previously? I dialled the number and played it straight; I introduced myself and asked if she knew John Fowles in Poitiers in the early 1950s. There was a long pause and I expected the phone to go down. But then a faint voice said: “Yes I knew John Fowles.” What went through her mind at that point? A complete stranger interrupting her quiet life with questions from a lifetime ago. We chatted a bit and she seemed not to be too disturbed by my impertinence. We arranged to meet the following week.

And so began a conversation that transported us back to 1951 with a description of a young poet/novelist just starting his career. Ginette is now a neat but frail lady, hard of hearing but with that sharp intelligence still intact. She became an English teacher and never married. She has no surviving family. She described Fowles as a difficult person, confident but reserved, ironic and proud. He was writing constantly, poetry and prose. It was obvious then, she said, that he wanted to write novels that were challenging and different.

It is clear from his Journals that, as summer approached in 1951, his love had begun to cool. Their relationship effectively ended at the close of that academic year as he was leaving Poitiers. It was a difficult parting, and he reports Ginette saying “I wish I had never met you”. He describes a final meeting on 22 August in which “she had never seemed prettier to me”, a “just and dignified letter” from Ginette on 5 September, and, on 6 December, another letter: “for her all is over, dry bones … end is inevitable”. On 26 December, on the eve of his departure for Greece and a new teaching job, he looks over his shoulder briefly: “I shall not find a Ginette again”.

She noticed when he became famous many years later, and did read his novels. I asked if she had any letters or photographs from the Poitiers period. “He gave me a passport photo but I lost that ages ago. I had lots of letters from him but I had a clear out not so long ago and they’ve all gone.” She seemed happy to talk but there remained a formality and a reticence, and I didn’t want to impose any longer. We agreed to stay in touch.

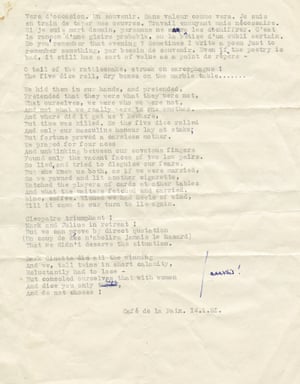

A few weeks later Ginette called me. “I think I’ve found something that you might want to see. Come round.” On her table was a thin piece of typed paper; a paragraph of prose and a poem. The prose is a mixture of French and English, which was how John and Ginette spoke together.

Occasional verse. A souvenir. Without value as verse. I am in the process of typing my complete work. Boring work but necessary. If I die tomorrow no one will be able to decode it. It’s the ransom of likely glory, or the stupidity of certainly being forgotten. Do you remember that evening? Sometimes I write a poem just to remember something, a need to keep a souvenir. Even if the poetry is bad, it still has a sort of value as a point of reference.

Then there was the poem, with no title but an inscription at the bottom: Café de la Paix 14.1.51. Ginette explained: “The Café de la Paix was where all the students used to gather together. It’s a poem from John to me.”

Back home I immediately cross check with the Journal. And there, as part of the same entry for Sunday 7 January when he first mentions his “fractional interest” in Ginette, is the following:

Feel ill and spend the whole evening playing dice with Ginette and Phil. Ginette, dark, vivacious in a not too gleaming way. With fine dark malicious eyes. She treats with a certain mock respect our student-lecturer relationship. I taught them liar’s dice. We played till midnight.

Ginette is puzzled why anyone would be interested in this story. On the face of it, it is of minor interest; a footnote to a footnote in literary history. But on the other hand it is a chance encounter that has opened a door into a room full of memories. I am holding a fragile piece of paper, an unpublished poem that marks the beginning of the first real love affair of a celebrated British writer. I have a picture of a French provincial cafe full of noisy students in a fog of filterless Gitanes, drinking coffee and cheap red wine and arguing about Jean-Paul Sartre. And in the middle of it are John and Ginette playing dice, falling in love. It’s a piece of paper that almost disappeared, but which survived. If I don’t write it down now, it will be lost forever.

2008.1.5 幾年前讀 John Fowles 的小說{The French Lieutenant's Woman 法國中尉的女人}

很對胃口

那時候 誠品進口他兩大冊的日記 現在似乎還在台大店的架上

我買一本Dell 版The Magus (1965/1978)(第42刷 ) 準備當睡前讀物

看到一篇 BBC的訪問稿 就將它複製如下 (所有加工都是HC作的)

A BBC interview with John Fowles from October 1977

On October 23, 1977, John Fowles was interviewed by Melvyn Bragg for the BBC Television show "The Lively Arts." The following is a transcript.

MELVYN BRAGG:

John Fowles is one of the handful of British authors treated with respect by the press and with delight by a wide public. Only a few writers of serious fiction sell tens of thousands of hardback books in this country. Fewer still sell hundreds of thousands in America. His new book is a novel called Daniel Martin. It is his fourth novel and that too, according to the publishers here and abroad, will scale the heights of bestsellerdom and also claim top billing on the serious review pages.

The Collector was John Fowles' first novel. It was made into a film in which Terence Stamp played the young man whose obsession for collecting butterflies was accompanied by an obsession to collect and make a captive of a young girl fromWikipedia article "Hampstead". Hampstead is the place John Fowles was living in at the time.

But the novel which made him an international literary celebrity was The Magus. It sold a staggering 4 million copies all over the world. He wrote it several times over a period of nine or ten years while he was in and around Hampstead in his 20s and 30s and it is a story of the trials and torments inflicted on a young schoolteacher on a Greek island in the 1950s. For reasons which were increasingly mysterious he's subjected to an immense series of ordeals and tricks and like all John Fowles' novels the metaphysics and the reflections are laid on as thickly as the dramatic plotting. Fowles is 51, he's married and with his wife he lives in a beautiful house in Lyme Regis overlooking the Cobb, which is where another of his novels, The French Lieutenant's Woman had some notable scenes. His garden reflects his passion for botany and his house is as large and roomy as his books. 這房子他生前有意捐給某大學當寫作教室 不過該大學因為無維護之財而晚謝 現在不知道情況如何(2008)

MELVYN BRAGG:

You've said yourself, I believe, that novelists are formed very young indeed, whether they know it or not. Is it possible to be at all precise about the way you were formed as a novelist?

JOHN FOWLES:

I meant that statement in general…what I feel about it would apply to any novelist. What interests me about novelists as a species is the obsessiveness of the activity, the fact that novelists have to go on writing. I think that probably must come from a sense of the irrecoverable. In every novelist's life there is some more acute sense of loss than with other people, and I suppose I must have felt that. I didn't realize it, I suppose, till the last ten or fifteen years. In fact you have to write novels to begin to understand this. There's a kind of backwardness in the novel…an attempt to get back to a lost world.

BRAGG:

Given that that is shared, then what specifically in your case would you say about your childhood that led or would lead a future biographer to say: Oh, yes, already he was this, that or the other?

FOWLES:

I was brought up at Leigh on Sea, which is a suburban town, part of Southend on Sea. I led the normal life of a suburban middle-class child, but the snag was that standing in the way of a smooth progression to a normal suburban middle-class adulthood was a love of nature. I can remember even as a small child that I always adored green things, I adored going out in the country. I was fortunate. I had an uncle who was a natural historian, and a cousin who was also a natural historian and those were the highlights of my first ten years, going out to look for butterflies or birdwatching, country walks. Then Hitler helped me greatly because we were evacuated to Devon and I had five years in a remote Devon village. That was a formative experience for me. I was a lonely child, but my friend was always nature, rather than being the company of other boys.

BRAGG:

When you say you were lonely, do you find, did you think that that sort of solitude was enriching on the one hand, and on the other hand good training for the solitary life of a novelist?

FOWLES:

I think solitude is a very, very good signal of the future novelist, an inability ...

BRAGG:

Or loneliness, which? Solitude or loneliness because you can be lonely without being solitary ...?

FOWLES:

Yes, you're quite right to make that distinction. I think a sense of personal loneliness, yes, is a better definition of it. I wasn't solitary in a sense, of course. I went to school and all the rest of it, but I think now that if I was shown a class of children and asked can you pick out the future novelists, I would look for the ones who are actually probably inarticulate. Above all, the ones who do not at any given present contraction of events show up well, the people who back down in an argument and who then walk away inventing a new scenario for the argument that has happened. It's important for a novelist to live in two worlds, and that I would say is really the major predisposing factor…an inability to live in reality, so you have to escape into unreal worlds. I would say this is true of all art as a matter of fact, but perhaps above all for the novelist.

BRAGG:

This is you now in 1977. Do you remember feeling this when you were about 15 or 16?

FOWLES:

No, not at all.

BRAGG:

Because you were head boy at school, good at cricket, that sort of thing, which would seem to be ...

FOWLES:

Yes, yes. I was a split child, certainly, yes. I mean I was quite good at cricket and I adored the game. I still adore it. I mean you know when the test matches are on, no work gets done in this house, but still. I also had a peak in my cricketing career…I had Leary Constantine second ball once, for a duck. I feel, you know, after that I couldn't really progress much. That sort of public school, First Eleven cricket, where you did during the war have a certain number of test cricketers and county cricketers playing against you, that was lovely.

BRAGG:

There's one picture not only of 20th century English writers going through public school and hating it and rebelling against it, and being, by their own account anyway, unnecessarily victimized at it and not good at what public school expects them to be good at. Did that in part or in whole happen to you too?

FOWLES:

I was not happy for the first two years of public school. I went through the stock experience, but then I suppose I joined the system, because you know public schools are cunning at brainwashing little boys. I was certainly brainwashed by this. Public school head boys at that period had extraordinary power. I was in fact responsible for the discipline of 600 boys and so every day I had to organise patrols…you know to catch boys out after lock-up, and all the rest of it. Every day I had a court in which I was both judge and executioner. It's terrible now when you ... I hate meeting old boys校友 from that school because I keep on thinking, did I once beat them?

BRAGG:

But at the time you didn't feel guilty. You felt this was the way it was?

FOWLES:

I joined the system. Then again the war helped me because I went straight into the Royal Marines. From having been a little gauleiter in school, I was right at the bottom in the Royal Marines and I loathed that comprehensively. The Marines helped me discover what I was, which was a profound hater of all authority, all externally imposed discipline. I really think I shook off the whole public school thing in those two years. One doesn't shake off those things immediately, but fairly soon afterwards, certainly by the time I'd finished at Oxford, I felt I was a different person.

BRAGG:

At Oxford University, you read?

FOWLES:

I read French.

BRAGG:

Did you start writing at Oxford, or had you started writing at school?

FOWLES:

No, no, no, I did that late. I think possibly in my last year at Oxford I was timidly trying to write poetry, at that time.

BRAGG:

Yes.

FOWLES:

I was really much more involved in a small set of friends at my own college, cricket playing and drinking, botanising, doing a little work, but I mean in those…you see we had three years without any examination. You just had finals, with the result that nobody really worked until the last six months of your three years.

BRAGG:

So those three years at Oxford were sort of mulling around and working out your own interests, were they?

FOWLES:

Absolutely. You say that rather dismissively.

BRAGG:

No I don't, no I think it's very…

FOWLES:

But in fact they were valuable in discovering or getting a slightly clearer focus on what you are. I was a much more confused than diffused personality than I…

BRAGG:

I think actually, I must correct that, because I don't think it's dismissive at all, if everybody's given the chance, which I was too. I took the chance of three years' licensed rumination, it's a marvellous way to spend those particular three years.━━ v. 反芻(はんすう)する; 沈思[黙想]する.

ru・mi・na・tion

ru・mi・na・tion

━━ n.

━━ n.

FOWLES:

Absolutely, what a nice way of saying it. This is what I hate about modern Oxford, you know. I mean the pressure on you to achieve destroys the great value of the Oxford and Cambridge system…the drifting, the not knowing where you were going.

BRAGG:

And did you come out of Oxford, you'd landed in, in a sense, the traditional…this isn't dismissive, but it is fairly accurately descriptive…the traditional dumping ground of Oxford graduates who didn't quite know what to do. They sort of lumped themselves into some sort of teaching or other ... didn't they?lump (ACCEPT) Show phonetics

verb INFORMAL

lump it to accept a situation or decision although you do not like it:

The decision has been made, so if Tom doesn't like it, he can lump it.

(from Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary)

FOWLES:

Yes.

BRAGG:

In your generation?

FOWLES:

I went for a year and taught in a French university, which sounds rather grand, but I was a kind of glorified assistant. Which again was an interesting experience, and a lonely one, but I had a year in a French provincial town.

BRAGG:

Whereabouts was that?

FOWLES: Wikipedia article "Poitiers".

Poitiers, and I made French friends. Another thing about my generation, of course, is that because of the war, abroad hit us much later than anyone else. That was a kind of love affair with France which I've never got over, which I still have. And from there, I could at one point have gone to Winchester and become a public school master. I had one or two other quite interesting jobs offered, but I took a peculiar one. This was to teach in a Greek boarding school, the so-called Eton of Greece, not because I wanted to teach there but because I wanted to stay abroad longer. I had two years there.

BRAGG:

This was on the island of ...?

FOWLES: Wikipedia article "Spetses".

Spetse. And again I had another love affair, with Greece, which was a different country in those days.

BRAGG:

But again was that quite lonely and was there a lot of private reading.

FOWLES:

We did a lot of reading. In the book I based on all that, The Magus, there's only one Englishman at the school…there were always two Englishmen in fact…and I made a good and lifelong friend during my stay there. And you know one made Greek friends.

BRAGG:

After that did you feel that you wanted to push on somewhere else?

FOWLES:

Greece really was the thing that drove me to want to write. I was writing a little there. I came back to England and I could say now that I made one or two intelligent choices for a writer. That is, I took bad jobs when I was offered better ones, but again I think ...

BRAGG:

Why do you think that's intelligent?

FOWLES:

Because if you are going to become a novelist you've got to take a job which doesn't take too much of you. Writing novels is a time-consuming, psyche-consuming business. I mean I don't think a good teacher actually would be likely to write good novels. A bad teacher might because he wouldn't be giving too much of himself in class and there's also the simple time problem, you know. Teaching is useful of course, because it does give you free time.

BRAGG:

Yes, so which bad jobs did you take?

FOWLES:

I taught for a year in an adult education college in Hertfordshire, Ashridge. Again, that was interesting because they were doing courses then where management and trade union officials met. This was the first time I'd really met socialists and listened to the socialist line being properly put.

BRAGG:

Did it educate you into politics? I mean did it change your politics?

FOWLES:

I'm not a political being really. One of my theories is that the problems facing the world at the moment cannot be dealt with politically. I would much rather see a takeover by the sociologists and biologists. I think we're facing a biological crisis now and I don't think the terms of contemporary politics really meet the situation at all.

BRAGG:

Biological crisis in terms of ...?

FOWLES:

In terms of overpopulation.

BRAGG:

Energy resources ...

FOWLES:

Energy resources, pollution and all the rest of it.

BRAGG:

You don't think those are being brought under control?

FOWLES:

I don't think they're being brought under control. I don't see how they can be, when the question is discussed nine-tenths of the time, in terms of labour and capital and all Tories and Labour party. The French have a new group. They call themselves "les Verts". An analogy with "les Rouges", the Reds. Now, if we had a Green Party in this country I should join that at once. That is, an ecological and a scientifically based country. I think only the scientists can really run society now and make decisions about the future.

BRAGG:

Do you think it's ever likely to come about that they'll be given the chance to?

Fowles:

Philosophers be kings? No, not until there's an appalling bloodbath and a universal catastrophe.

BRAGG:

But these jobs in England, were essentially teaching jobs that you did?

FOWLES:

Yes, yes. I taught for many years in Hampstead, in a secretarial college…foreign students…which I enjoyed much. But you haven't really lived life until you've taught Siamese girls or taken Siamese girls through Macbeth. I remember we did Romeo and Juliet, and they could not understand what was tragic about Romeo and Juliet because they'd disobeyed their parents, so they deserved everything that was coming to them. But it was fun.

BRAGG:

When you said these jobs didn't take a great deal of your time, though did they? They were ...

FOWLES:

Well they did, they did in the sense I knew they were not really what I wanted to be doing. They took time but I found I could cut off fairly easily when I got home. I wrote The Collector in the evenings really. In fact I wrote it in one month during the holidays. The first draft of it. In a way that pressure's good for a young…I know young writers think, "Oh, if only I had more time" ... time to think. But in a way I think that kind of pressure is good for a young writer.

BRAGG:

You started writing then in your mid twenties, is that ...?

FOWLES:

I should ... yes, I should think it was about then.

BRAGG:

But it wasn't until you were almost in your mid or late thirties that the first novel came out?

FOWLES:

Yes.

BRAGG:

What were those ten years like while you were writing but not being published? Were you in a state of expectation or frustration or both or what?

FOWLES:

I think mainly frustration, yes. It wasn't that I was submitting novels and getting them rejected. I just knew they weren't good enough. Partly I was also bound up with The Magus during that period and I just knew it wasn't what it had to be and again and again I would spend six months, nine months on that, and again I'd know I was defeated and put it away. I really wrote The Collector to try and get out of the sort of quagmire I felt I was in over The Magus.

BRAGG:

You said you wrote that in a month?

FOWLES:

I wrote the first draft in a month, yes, and I revised it considerably. I didn't take a month, you know, between my starting and my completed work.

BRAGG:

Was it snapped up instantly as a film?

FOWLES:

I can't remember the exact time lapse ... yes, fairly soon.

BRAGG:

And that enabled you to pack in teaching, did it?

FOWLES:

Yes, I think I sold it for 5,000 which was I suppose a bargain, but I never regretted getting that money. That did set me free from teaching.

BRAGG:

Did you give up teaching instantly and say: O.K. this is it, I'm going to be a writer full time?

FOWLES:

Yes, almost.

BRAGG:

And what did that entail? Did you rush off into the country or did you stay ...?

FOWLES:

No, we went on living in London for, I can't remember now, two or three years. I then began to feel that as I don't like the literary life and all the rest of it, I didn't like London any more. Not because of London, but I don't like big cities any more. I also felt an increasing draw towards the country, and so simply one day we set out and started looking for a house. It's not really because one or two of my ancestors are West Country people. In as much as I feel I have a home province in England, it's certainly the West of England. It's partly to do with the fact that I spent those war years in Devon. My father's ancestors came from the Somerset/Dorset border. I have a Cornish grandmother. It's something to do with the temperament of the West of England which has always appealed to me.

BRAGG:

Did you come here then principally for the landscape or did you build much of a social life, an anti-literary life here, or ...?

FOWLES:

No, not at all. I've never needed other human beings really, I suppose, which doesn't mean to say I don't enjoy meeting them sometimes, but I need other people less than most. It's much more to do with mysterious things like climate, the sort of precocity of the West of England, that's something I've always loved. The fact that spring starts here a little bit earlier than it does up country, and I adore the sea. I don't think I could live now out of sound of the sea. I'm one of those mysterious people who loves coasts, beaches, shores, and if I had to define a perfect place to live my one constituent would always be that you go to sleep with the sound of the sea somewhere.

BRAGG:

In The Magus there's a lot of…as in many of your novels, most I think, but particularly marked in The Magus…there are games always being played. The God Game was the original title, or was a possible title for it ...?

FOWLES:

Yes.

BRAGG:

And the games are varied and ingenious…but they're all about the same thing. Whether people are…whether this is truth or it's lies, and whether the lies are nearer the truth, and what is supposed to be the truth, and the difference between truth and lies. And also the difference between or the comparisons between truth and fiction?

FOWLES:

The way into the novel happens to lie there. I would not call this a general recipe for the novel. It's just possibly because I have been very attached to French culture…I have read a good deal about the new novel theory…that perhaps I'm more aware of the sort of fictionality of fiction than most English writers. That doesn't mean that I think the truths that are put across in the artifice of fiction are necessarily artificial truths, they are just different from philosophical propositions or scientific truths. Perhaps they are 'feeling' truths. In a novel I've just written I use a phrase 'right feeling'. In a way the novel is about how to feel right. I think people are amenable to such truths. They may not analyse it as much as the novelist himself does, but I don't think they require of a truth that it is sort of arguably verifiable. I think they are prepared to feel through a novel. Most of the novelists I admire in fact do communicate mainly through feeling… Lawrence, Hardy and so on.

BRAGG:

Why do you want then to play so many games on your reader by telling him something and then saying. 'No, that isn't true.' In The Magus, Conchis is constantly saying ...

FOWLES:

That is true of The Magus, which was deliberately conceived as a game novel, or a games novel, if you like, in its final phase. I don't really consider that the games I played in The French Lieutenant's Woman are games. You know, I gave two endings or three endings possibly. I did at one point step out of the sort of illusion of fiction, into another illusion. I don't really feel that those are games. I think those are in fact literary truths, which can be stated.

BRAGG:

And literary truths are to do with right feeling?

FOWLES:

Some literary truths are about the nature of fiction. The ones I've just mentioned in The French Lieutenant's Woman are in my view truths about the artificial nature of fiction, but that has nothing to do with other kinds of truths in the book, which really are about feeling, and which of course do express opinions about life. I would consider myself a socialist, but I don't think the novel's really the right place for explicit socialist propaganda. The right place for that is the essay or the non-fiction book, or obviously the actual involvement in politics.

BRAGG:

Do you think your socialism comes through in your books despite ...?

FOWLES:

That I do not know. I do not know, but I made a kind of resolution many years ago that I would not put too many of my personal political views into my novels. If they are put in they are filtered in and ...

BRAGG:

But you put a lot of…I have the impression that you put a lot of your own personal philosophical views into your novels.

FOWLES:

Yes I do, yes, yes.

BRAGG:

Why is the novel therefore more capable of bearing philosophical views than political views?

FOWLES:

Well ... I do that, but that is possibly wrong because I don't think any serious philosophy can be established through a novel. I don't see that that's possible. Opinions about how life functions and the kind of stress you give on to various modes of living and all the rest of it. That is the personal opinion of the novelist. Of course, it's for the reader to accept or reject.

BRAGG:

How high ...?

FOWLES:

If you think of Jane Austen, there's really nothing of any philosophical value in any of her work. But we all know that she did feel her way to a certain central moral position, which has been of great importance in English literature and, I would argue, in English life. It's informed a lot of English middle class life.

BRAGG:

You're constantly referring to other writers, a lot of English writers. Do you feel yourself very much part of a company and a tradition of writers?

FOWLES:

I feel myself very much, although many reviewers would tell me I'm not, but very much in the English tradition, although I've been much more influenced than most English writers by French culture. There are no modern schools of English novelists. I think this is one of the troubles of the English novel. We all live so far apart, we're disconnected. We also get absolutely no backing from English universities. I don't think everything is wrong, you know, about the backing that American universities do give fiction and the problems of fiction. And some of the American theoretical work on fiction is good. I don't agree with it all, but at least it's alive and it's being discussed. In this country you have to be dead for anyone to take any serious notice of you. The English part of me understands that. Perhaps it's a good principle to say, you know, until a person's dead then forget him or push him down, but it doesn't help the novel in general.

BRAGG:

Do you feel although you live in Lyme Regis, do you feel yourself to be an exile here?

FOWLES:

For many years I have felt in exile from English society, perhaps particularly English middle class society. I've never felt an exile from England itself, from its climate, its countryside, its cities, its past, its art, but yes, yes, I do feel in exile. I think this is a good thing for a novelist. If a novelist isn't in exile I suspect he'd be in trouble.

BRAGG:

Why?

FOWLES:

Because I think if you're fully identified with society then you probably would be in another career. You would be active in society and I don't think you would get that essential distance, the ability to judge and to criticize society, because another important function of the novel as we all know is to correct society, to criticize it.

BRAGG:

And you think that the novel still has the power to do that even today?

FOWLES:

Oh yes ... I'm sure. Whether the actual contemporary English novel is doing it I don't know, but I'm sure it has the power to do it, yes. I mean Solzhenitsyn has obviously done it recently with Russia, I should have thought Bellow has done it or did it in Herzog, in America. Joe Heller has done it I think for America. I don't think it's beyond the capacity of the novel. It may be beyond the capacity of the contemporary English novelist.

BRAGG:

Have you ever thought of moving abroad, then, feeling so much in exile from Englishness? Have you ever considered going and writing in ...?

FOWLES:

No, because as I say I feel in exile from various aspects of English society, but not from England. Yes like all successful authors, in financial terms, I've wondered if I can take the tax situation. But since I am a socialist, since I believe that the rich should be heavily taxed anyway, I can see it would be wrong. I also believe that novelists, of all artists, should live in the culture where their dialect, where the language is spoken. I don't think it helps the novelist at all, except in one or two exceptional cases, to go into literal physical exile from his society. To live in an environment with another language, another culture, and all the rest of it.

BRAGG:

You have said one of the themes of Daniel Martin, which is the novel that's just out, is Englishness. What do you mean by Englishness?

FOWLES:

Well, countless things, really. But I suppose principally games-playing, rarely saying what you truly mean, a certain greenness, a certain innocence however sophisticated we appear to be, a certain bloody‑mindedness, whatever it is that distinguishes us from the Welsh, the Scots, the Australians and the Americans.

BRAGG:

When you said games playing did you mean playing of games like cricket?

FOWLES:

Well I'm talking more or less about the middle-class English. No I mean games-playing much more in the Stephen Potter sense, the way that most middle-class conversation…people are really not exactly scoring points, but English people are I think chary of saying what they really feel and they really mean. This I mean ...

BRAGG:

You say this is middle class?

FOWLES:

I detect traces of it elsewhere in the English class system, but I think it's specifically a middle-class thing. For me this is one thing which distinguishes us clearly from America. Every Englishman who goes to America has problems with irony. There are all kinds of ironic things which you can say to another Englishman, which the American, even the intelligent American, won't get. You have to say what you mean there to communicate.

BRAGG:

Do you find that restrictive?

FOWLES:

In an odd way I both like and dislike it. For months in America it's marvellous. People are actually saying what they mean, they're frank, they're honest, they're straight, and then you start longing for English deviousness and joking. I remember having a rather grim three weeks in Hollywood once and I got tired of this American directness. By chance somebody introduced me to Peter Ustinov. I had an evening alone with him and that was absolutely marvellous. It wasn't because he was a funny man, a great storyteller, but it was meeting another mind who knows all the facts about English games-playing you know.

BRAGG:

In The Magus another point you bring out very strongly is the belief inside the book, which might be your own or not, I don't know, of the importance of hazard. That's the word you keep using. You use it in The French Lieutenant's Woman as well, quite freely ... but you use, let's stick to The Magus, you use it a lot there. What do you mean by that?

FOWLES:

I suppose this comes from the natural history side of my life. If you watch nature closely you cannot help noticing the part that hazard plays in ordinary behaviourisms of the commonest birds, animals and plants, and so on. I find in my own writing that it is an enormously hazardous procedure and I don't mean hazardous in quite the sense of risky or dangerous, but I mean in a…hazard plays an enormous part in it. I don't know where good ideas come from. I don't know why some mornings the words come right and other mornings they won't come right. I don't know why characters do not do what you plan for them. This seems silly. You've invented a character. The character should be absolutely your creature but as I'm sure you know there are mysterious times when characters say, "I will not talk like that. You may have planned this but I will not do it." You overrule these situations, you deny their existence at a great cost. For me, this is fundamentally a matter of hazard. You know, there is a mystery there.

BRAGG:

Why are you so keen to promote the idea that there should be a cultivation of the notion of mystery?

FOWLES:

Oddly enough, I don't think certainty makes for happiness in a human being. I think one piece of strong evidence that people do lack mystery is the enormous success of one literary genre, that's the mystery story, detective story, the spy thriller. As we all know, commercially they have been the most successful type of literature of this century. I think that has come about largely because of the illusion that science has solved all our problems, when most people are in their ordinary life, they consciously or unconsciously know that a lot that happens just isn't explained. And I think all art also is really bound up with (1), the idea of the unknown and (2), the idea of the unknowable, the impossible.

BRAGG:

How do you ...?

FOWLES:

Mystery for me has energy, you know absolutely fixed answers destroy something, they're a kind of prison, although obviously there are areas where you have to know the answer.

BRAGG:

Would you say that Daniel Martin was a departure for you…is it continuing? It's certainly continuing themes that have interested you before, but in what ways would you say it was a departure?

FOWLES:

It's a tiny bit of a departure in that it deals with present times, it's a little bit closer to myself than ... although I'm not Daniel Martin, but it certainly is closer to a part of myself and the style I suppose is more realistic. I'm not sure that I will stick with this but I did want to ... a novel that's always haunted me is Flaubert's Sentimental Education. It was a little, it was slightly behind The French Lieutenant's Woman and it's slightly behind this one too…that is the sort of massive social documentary novel. I mean the attempt to portray an age or aspects of an age.

BRAGG:

Given such an age, then, in such an age where science is ... you've said yourself that you think the only people who can solve the problems of the world are scientists, where, crudely as it were, does art fit in?

FOWLES:

I would start humbly, at entertainment. I've never seen anything wrong in the notion of art as a kind of time-filler, a time occupier. One thing that seems to me to have gone wrong with the British novel and the American novel is this notion the novelist has to write for an intellectual élite. What modern novelists can only look back on with great sadness is the kind of relationship the great Victorian novelists had with their public. You know when the Victorian novelist says, "I am writing for a wide audience." I want to attract a wide audience and I think we've gone far too much along the road of it being a kind of hermetic thing, you know. The novel is for some kind of professional novel reader.

BRAGG:

Television's taken over that ambition to appeal to a wide audience.

FOWLES:

Yes, yes, but that's no reason for the novel to say, all right then I'm freed from that task, I can now turn in and look after my own elite. I am as it so happens often tempted to write more complicatedly and to use for the sake of a better word a more avant garde style than I actually use, but I mean this is…I regard a little bit of a socialist's duty in the writer, if you do adhere to the principles of socialism, you should in fact not try and cut yourself off from a wide audience. If you can attract it, if you can write for it, then you ought to.

BRAGG:

Where does the 'ought' come in? You've said that the writer was somewhere between a preacher and a teacher. That statement does sound rather…

FOWLES:

Of course I cannot deny that I have things I'd like to teach people. It may be only about feeling, but I am an opinionated writer, yes.

BRAGG:

What things would you say you wanted to teach people?

FOWLES:

For lack of a better word, humanism, yes, I think more humanist, more intelligence.

BRAGG:

Humanism meaning what?

FOWLES:

Well, it's a difficult word to define, but I suppose I mean something simple, like respect for other human beings. I suppose largely the liberal tradition, or, to use an 18th century word, the enlightened tradition in European life. I'm fond of the literature of the enlightenment, the European enlightenment. You know, whatever continues from that into our own age.

BRAGG:

Do you believe that it's important for people to…both people and the characters in your books…to understand as much as possible?

FOWLES:

I always like one character in my book in that situation, because I find that gives the book a kind of onwardness. A sort of archetypal image I have which I associate with the novel is that of the voyage. This, the learning novel where the central character or a main character has to learn something, does give a kind of energy to narrative, and it does catch out the reader because most readers also want to learn something. So it's a kind of engine. I think it's an engine in the book.

BRAGG:

You've talked about narrative. Do you find that being a storyteller, to put it at its most modest, is something that came naturally to you or is it something that you work at and try to make the narrative ...?

FOWLES:

No, I don't have to work at it, because it so happens that all through my life, ever since I was a small boy, I've loved story above everything else. Far more than the quality or the feel, the style of writing. I've loved pure narrative. That's why I've said several times that I regard my grandfather in English fiction as Daniel Defoe, because I love that extraordinary readability of Defoe, the way he pulls you on. I don't know why I have a gift, if I have, for storytelling in particular. I don't know why it attracts me. There are all kinds of writers I can admire on intellectual grounds, George Eliot, for instance, but I can never get on with them because I feel the story element, except in Middlemarch, somehow isn't strong enough. There are few writers who can write well enough in other areas of writing, yet who fail in story, who will interest me. Virginia Woolf…I can stand her lack of narrative ability because she's such a superb writer in other ways. Joyce, obviously, but there are not many. It puts me out of touch with a great deal of modern writing, of course ...

BRAGG:

Why do you think that a great deal of modern writing has lost interest and lost energy for narration…for narrative? We're always talking about a division in modern writing which is bridged by very few people, and you may well be one of them, between, what is thought by a small group of literati in New York and London to be very good, which is not at all widely known, and what is widely known which is thought by this small group to be not at all good. The good and the well-known, the good and the popular…there is a sort of a chasm between the two, isn't there?

FOWLES:

I think the intellectual literary creams of both London and New York have really lost touch with what the function of literature should be.

BRAGG:

Do you think, is it London, or do you think it's more the academic influence?

FOWLES:

Well, the academic…you see, the academic worlds have not helped one bit by over-praising what to my mind is pseudo-intellectual, it's not truly intellectual. It has a surface gloss of avant gardism, experimentalism, intellectualism, what you want…and I think that this is a treachery of the clerks. It's also to my mind profoundly unsocialist. The great unknown literary critic in my view of the last fifty years is George Lucaks, the Hungarian. He had faults that we all know, but his message has just not got across, I think, in the west. His message is not fundamentally to my mind a Marxist one. It's much more a humanist one.

BRAGG:

How would you describe it, his message?

FOWLES:

Well I think that whatever his political views, the writer should not be too swayed by intellectual fashion. There is a certain kind of contract which we were talking about just now, between the novelist and a reasonably wide audience. If the novelist uses an experimentalist style, experimental techniques, all right he's at perfect liberty to do that, but I think he ought to ask himself the question of what good am I doing? In general he's preaching to the converted, to the rest of avant garde, but there are all those other people out there who cannot appreciate that kind of writing. He's missing out on them totally and that for me is not what socialism is about.

BRAGG:

I agree.

FOWLES:

It's not what humanism is about. No, I tell you what I find terrible is the association between avant garde art and a certain branch of the New Left. You know, that iconoclastic experimental art must automatically be left wing. This is for me one of the great illusions of the age. I don't see how it can be, you know, because it is, however anti-establishment it may be, it is fundamentally highly élitist. It's hermetic, and it's just like all those late nineteenth century movements, symbolism and the rest.

BRAGG:

I think those…I agree with you there. I also think that the academic tone in criticism and the academic caucus which dominates many reviews in this country and in America looks for things which they, which they, proven virtues of the past, whether it's the 18th or the 19th century.

FOWLES:

They are shopkeepers. You know half the academics…critics in both America and England…are shopkeepers. They have a little trade in something, and they cling to that to a degree which I think is ludicrous. We really need a new Voltaire to…

BRAGG:

Mock them.

FOWLES:

Yes, to write a Candide about them, yes.

BRAGG:

Do you fancy doing it?

FOWLES:

I haven't alas got that kind of wit. We need a new George Orwell, and he's not about, alas.

BRAGG:

When you left your job and became a full-time writer…is the easiest way, did you find it a strain or did you find you accommodated to it quite easily and happily?

FOWLES:

Very, very happily. I suppose there's something wicked and pagan in me but I've never really admired work much. I've never seen any great virtue in doing work which you don't enjoy. I don't regard writing as work, you know. It's so pleasurable that even when it's going badly, it's pleasurable. It's much more work for me to get through life when I'm not writing.

BRAGG:

How do you go about a novel? Do you write every day when you start a novel?

FOWLES:

No, I don't keep to any plan at all. I never write unless I feel like it, except during one phase, which is the last one when you're revising and you have to be a sort of schoolmaster to yourself. But certainly in the first draft…I find it difficult to describe. You just know that it will flow and then I will work hard sometimes, for fourteen hours a day, something like that, but normally I've no plans, no fixed routines, nothing.

BRAGG:

Do you have any pattern in your reading, or do you just read what comes?

FOWLES:

Absolutely none, that's the same. I collect old books, not for their value, not for first edition reasons, nothing like that. I collect them because I love out-of-the-way novels, out-of-the-way memoirs, out-of-the-way plays…the sort of books that most other people have forgotten. I suppose I have a good collection now of books that nobody in their book-collecting senses would ever want to possess. What I like about any kind of book is a kind of time machine thing. The something which takes you back to the actual time in which it was set, which is I'm fond of historical memoirs. I love the feel of suddenly being alive again two hundred years ago. Old trials, I'm fond of old murder trials. Of course they also give you that feeling sometimes, you know of refilming in a way, of existing in other people's minds in the past.

BRAGG:

You said you didn't particularly or you didn't at all like the literary life in London. Do you not like any part of the literary life at all? Or does it worry you, being a literary figure?

FOWLES:

Well, in my private life I'm not a literary figure. None of my close friends are literary people. It depends what you mean by literary life. I do know one other writer quite well, but we never discuss books or writing, or hardly at all. But the sort of circuit of cocktail parties, publishers' parties and all that business, no, absolutely not.

BRAGG:

I was just thinking of something Daniel Martin says in the book. He says, "All art from the finest poetry to the sleaziest strip show has the same clause written in. You will henceforth put yourself on public show, and suffer all that entails."

FOWLES:

Yes, I think that's true.

BRAGG:

Well what in your case is entailed by putting yourself on public show?

FOWLES:

Mainly a problem of putting the truth, or something reasonably truthful, on show. Because like all a novelists, during any given conversation or course of events, I can also think of alternative ones. I'm not a great conversationalist, largely because I'm always constructing other conversations apart from the one that is actually going on and taking part in.

BRAGG:

Which conversation are you constructing at the moment, apart from the one that's going on?

FOWLES:

Well, I'm not at the moment because in these conditions it's rather difficult. I'm talking about more relaxed sort of private situations. Because one is a writer you construct better truth out of print which you can constantly revise and revise and revise, than you can from the one time only of any conversation. I mistrust spoken dialogue totally in the ordinary…not in an artistic sense, but in the ordinary context of a conversation. I don't think I could ever express myself fully in ordinary conversation. That's partly because constructing novels is as you know a rich complex experience and it's impossible I think really in any space shorter than the novel itself to fully convey it.

BRAGG:

Have you thought, I mean, do you think of the novel in comparison with poetry and plays? Do you think it can do things that other art, that the other arts cannot do?

FOWLES:

The novel, yes, I think does have definite territories that the other literary arts…

BRAGG:

I mean there is a very general boring sort of run, isn't there, that the novel is dead because of television, the cinema and so on ...?

FOWLES:

Oh that's nonsense, absolute nonsense.

BRAGG:

It is nonsense. Why do you think it is nonsense?

FOWLES:

There are all sorts of fairly obvious reasons. The fact that in a novel you can analyse thoughts and the unconscious in a way that cameras never can. There are various technical things. In a novel you can change locations, times, as easily as anything. That starts creating great problems when you have to start photographing, but I think a much more vital reason is that the word is not a precise image. If I say a sentence like, "She walked across the road" ... if that is in a film script and it is filmed, then all the viewer is going to see is one she, one walking across one road. In a novel it is the reader who actually has to contribute quite a lot. Each reader will see that sentence "She walked across the road" in a slightly different way, because he has to create it out of his own memory stock. Take the most famous novels, War and Peace, and Jane Austen, and of the millions and millions and millions of readers of these novels, no one has ever recreated it, no reader has ever recreated it in quite the same way. Now this for me is a marvellous richness which applies to poetry as well, about poetry and prose, that this is extraordinary freedom of communion. It is a kind of relationship between reader and writer. That has disappeared in the visual arts. The camera is a fascist thing. It says: this is the one image you're allowed to see and that overstamps this freedom of imagination which words, verbal signs, possess. That is why I'm absolutely sure that the novel possibly may die but prose, the verbal sign, can never die, poetry can never die.

沒有留言:

張貼留言

注意:只有此網誌的成員可以留言。