Aaron Swartz stood up for freedom and fairness – and was hounded to his death

The internet activist who paid the ultimate price for his combination of genius and conscience

On Monday, BBC Four screened a remarkable film in its Storyville series. The Internet’s Own Boy told the story of the life and tragic death of Aaron Swartz, the leading geek wunderkind of his generation who was hounded to suicide at the age of 26 by a vindictive US administration. The film is still available on BBC iPlayer, and if you do nothing else this weekend make time to watch it, because it’s the most revealing source of insights about how the state approaches the internet since Edward Snowden first broke cover.

To say Swartz was a prodigy is an understatement. As an unknown teenager he was a co-designer of tools – like RSS and Markdown and of services like Reddit – that shaped the evolution of the web. He was also the kid who wrote most of the code underpinning Creative Commons, an inspired system that uses copyright law to give ordinary people control over how their digital creations can be used by others.

I never met Aaron (though we had a mutual friend) but I spotted him early when he first surfaced as a blogger. What struck me instantly was the freshness and originality of his authorial voice. He was very young when he went to Stanford, and he wrote about the attitudes and social mores of his classmates, many of them brats of the American elite, with a raw freshness and naivete that was startling. He didn’t belong there; he felt himself an outsider; but at the same time he wasn’t judgmental, and ithat combination of candour and uncertainty was attractive and unusual.But Swartz was far more than an immensely-gifted programmer. The Storyville film includes home movies which show the entrancing, voraciously-inquisitive toddler who was father to the man. As he grew, he displayed the same open, questioning attitude to life one sees in other geniuses who are always asking “why?” and “why not?” and driving normal people nuts.

As he grew, one could see him becoming more and more interested in politics. And this too was predictable, for nobody with that razor-sharp intelligence could look at neoliberal capitalism and not see the unfairness, hypocrisy and inequality that lies beneath it. So he morphed into the most technologically-gifted political activist in history. He looked for instances of manifest unfairness and developed software to remedy it. Discovering that the provision of court transcripts in the US was essentially a commercial racket, he teamed up with other activists to right an obvious wrong: that the law was only readable by those with money.

He was similarly exercised at the fruits of taypayer-funded scientific research being monetised by a few ruthless publishing firms which charge outrageous fees to access the resulting academic papers. His first foray into this field involved downloading a trove of medical research papers and then data-mining them to uncover hitherto-undetected links between pharmaceutical firms and the authors of articles in prestigious journals.

One explanation for the vindictive prosecution puts it down to a politically ambitious federal attorney anxious to make a name for himself. But there is a darker, interpretation – that the authorities had noted how effective Swartz had become as an activist (he had, after all, mobilised the net community to stop the internet censorship legislation of the SOPA bill), and they were determined to make an example of him pour décourager les autres. Which, if true, would mean the Obama administration has taken a leaf out of the Chinese book on internet control: people can say more or less what they like online; but the moment they look like mobilising people, then you come down on them like the ton of bricks that crushed Aaron Swartz.His downfall came when he turned his attention to JSTOR, a digital library of academic articles hidden behind a paywall. He devised a method of downloading large numbers of articles from JSTOR, using a computer hidden in a closet at MIT. He was arrested in January 2011 and pursued by federal prosecutors with a vindictive zeal, eventually being indicted on a raft of charges which carried a potential jail sentence of 35 years. Ground down by this, he hanged himself on 11 January 2013. News of his death left countless people saddened and enraged. What had made the Feds so vindictive? Sure, he had broken the law. But it wasn’t as if he’d hacked a bank. What came to mind was Alexander Pope’s rhetorical question: Who breaks a butterfly upon a wheel?. “The act was harmless” wrote Tim Wu, a law professor at Columbia. “There was no actual physical harm, nor actual economic harm. The leak was found and plugged; JSTOR suffered no actual economic loss. It did not press charges. Like a pie in the face, Swartz’s act was annoying to its victim but of no lasting consequence.”

M.I.T. Releases Report on Role in Swartz Case

與世人共享學術論文

26歲的互聯網活動家亞倫•斯沃茨(Aaron Swartz)去世,理所當然地喚起了人們對其創意和無私的讚頌。最近,因從一家電子圖書館非法下載數百萬篇學術論文而面臨牢獄之災的斯沃茨自殺身亡。

五年前,斯沃茨簽署《游擊隊開放訪問宣言》(guerrilla open access manifesto),控訴“世界上全部的科學文化遺產”被“少數幾家私人公司數字化並封鎖起來”,如里德•愛思維爾公司(Reed Elsevier)。他建議計算機黑客“獲取儲存在任何地方的信息,製作備份,與全世界共享”。

2010年,他隱瞞身份,利用麻省理工學院(MIT)的電子網絡下載了Jstor數據庫的大部分內容。Jstor是一家將學術期刊和論文數字化的非營利機構。他沒有共享或出售這些資料,並於後來將其交還,但檢察官仍然認真追究了那份宣言,對斯沃茨提出詐騙指控。

斯沃茨參與過諸多項目,包括新聞聚合工具Reddit和開放版權許可的“創作共用”(Creative Commons),深受喜愛和敬仰。但他對學術研究和出版的分析卻存在著錯誤的理解。

斯沃茨倡導的學術研究免費訪問體係可為公眾帶來福利。在這樣的體系下,任何人均可以閱讀、分析並藉鑑私人和政府資助的研究成果。然而,仍有人要為此買單,麻省理工學院和牛津(Oxford)等大學付出的成本將不降反升。

現有體系下,專業資料圖書館為使用在線數據庫每年支付高達5萬美元。該體系的批評者將高昂的成本歸咎於里德•愛思維爾和Springer等公司的暴利行為。活動家、《衛報》(Guardian)作家喬治•蒙比奧特(George Monbiot)將其稱為“純粹的食利資本主義”(rentier capitalism),認為人們應當“拋棄這些寄生蟲般的大地主,解放本應屬於我們的研究成果。”

與之相關的一種觀點是,出版成本已隨著紙質印刷向數字化的轉變而顯著下降。2012年第一季度,里德•愛思維爾旗下的科學出版分部愛思維爾(Elsevier)營收9.78億英鎊,盈利3.52億英鎊——營業利潤率為36%。趕走資本家,通過公共渠道發表學術成果,一定能大幅減少成本嗎?

也許吧。愛思維爾確實需要更多的競爭。它的收費結構不透明,學者們爭相在它出版的期刊上發表論文。愛思維爾擁有沃倫•巴菲特(Warren Buffett)所稱的“護城河”——一個從業130年、佔有20%市場份額的企業是難以撼動的。

但這種優勢不是偷來的。20世紀60年代和70年代以來,研究型大學為了節省資金,將規模不大但成本高昂的出版業務外包,造就了愛思維爾的優勢。愛思維爾僱傭7000名編輯,管理著約50萬名(無償)同行評議專家組成的網絡,每年出版30萬篇新論文,並運營著100TB的數據庫。

印刷只佔學術出版成本的一小部分。大部分成本集中在編輯、審核投稿(其中三分之二被退稿)和管理數據的費力工作上。開放訪問的出版商也要付出類似的成本,例如愛思維爾的競爭對手、位於舊金山的公共科學圖書館(Plos)。

英國研究信息網絡(Research Information Network)的一項獨立研究發現,從印刷到數字的轉變可為全球節省10億英鎊——值得提倡,但它僅佔全部成本的12%。將私人公司剔除出去或許能節省更多成本,但同樣也可能降低效率。

不論如何,成本仍然高昂。行業中90%的企業實行訂閱制——正是斯沃茨恨之入骨的那種模式。另外10%的企業實行開放訪問,研究人員(或是研究贊助方)向期刊支付每篇論文1000至5000美元不等的發表費用,以彌補出版成本。之後任何人均可免費閱讀。

開放訪問很有吸引力,並且得到了美國國立衛生研究院(National Institutes of Health)和英國惠康基金會(Wellcome Trust)等研究基金和英國政府的支持。惠康基金會認為,如果每年投入7億英鎊的研究經費,卻不為推廣研究成果額外花費1000萬英鎊,是沒有意義的。

目前,研究成果的主要讀者是學者,他們大多能夠通過圖書館訪問論文。不過,拓寬讀者群可能擁有巨大的好處——開放訪問的科學期刊《Plos One》便是有趣資料的寶庫。

所以說,開放訪問主要是將帳單轉移了。英國研究資訊網路估計,如果90%的市場採用開放訪問,總成本將降低5.6億英鎊,但大學的支出將增加。英國的圖書館訂閱費用將省下1.28億英鎊,但要支付2.13億英鎊的發表費用,因為英國大學發表的研究數量很高。

開放訪問也有其問題。20世紀70年代,信用評級行業將收入模式從投資者訂閱付費變為向債券發行機構收費。這使得人人都可以看到評級,但評級機構也產生了用優質評級取悅發行機構的動機,最終導致不可靠的抵押貸款支持證券(MBS)紛紛獲得AAA評級。期刊的開放訪問也會有訪問群體拓寬、論文品質下降的傾向。值得注意的是,《Plos One》會錄用任何滿足其“科學有據”標準的論文投稿,它每年發表2.4萬篇研究論文,而大多數知名期刊(包括其他Plos刊物)每年只發表200篇。

如果斯沃茨之死能推動天平向開放訪問的一側傾斜,他的死也將有所意義。但總有人要為學術論文買單。

譯者/劉鑫

斯沃茨 | 1986-2013

RSS發明者斯沃茨自殺去世

報道 2013年01月15日

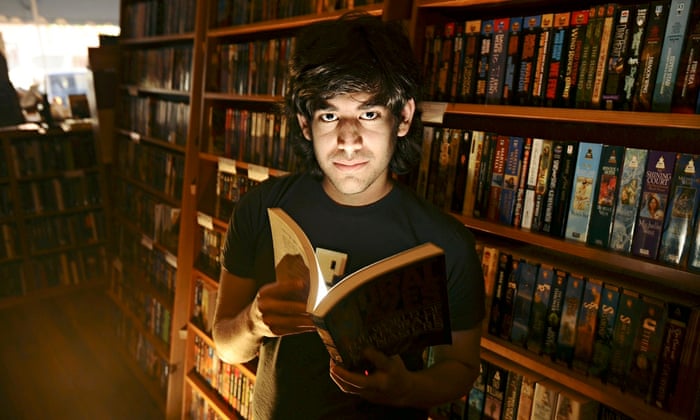

Michael Francis McElroy/The New York Times

阿龍·斯沃茨在2009年。有人在回憶他時,說他是個難以捉摸的天才。

周五,天才程序設計員阿龍·斯沃茨(Aaron Swartz)被發現在紐約的家中死亡。他十幾歲的時候,就協助編寫了能夠把實時更新的網絡內容傳輸給讀者的代碼,後來,成了一名讓人們能夠隨時隨地免費分享網絡信息的堅定倡導者。

斯沃茨的叔叔邁克爾·沃爾夫(Michael Wolf)說,26歲的斯沃茨應該是上吊自殺的。斯沃茨的一個朋友發現了他的屍體。

斯沃茨14歲的時候,就協助創造了“豐富站點摘要”(Rich Site Summary,簡稱RSS),這種工具幾乎無處不在,能夠讓用戶訂閱網絡信息。之後,他成了一名互聯網平民英雄,致力於使大量網絡文件成為免費公開的資 源。然而,2011年7月,聯邦政府指控他非法進入JSTOR(這是一個發佈科學和人文期刊的網站,只提供付費服務),並下載了480萬篇文章和文件,幾 乎是這個網絡圖書館的全部內容。

該案的指控包括電信欺詐和網絡欺詐。在斯沃茨死亡之時,這些指控尚未正式提出。他有可能面臨35年的監禁和100萬美元的罰款。

“阿龍創造的新技術令人驚訝,這些東西改變了信息在世界上的流通方式,”曾擔任奧巴馬政府科技顧問的紐約卡多佐法學院(Cardozo School of Law)教授蘇珊·克勞福德(Susan Crawford)說。她稱斯沃茨是個“難以捉摸的天才”,還說“計算機業的前輩們對他都會滿懷敬畏”。

沃爾夫說他會永遠銘記自己的侄子。過去,斯沃茨曾經寫下了與抑鬱和自殺想法作鬥爭的經歷。沃爾夫說,這個孩子“面對着這個世界,自己的大腦中存在一定的邏輯,而世界並不一定符合這個邏輯,所以這有時會很難。”

麻省理工學院(Massachusetts Institute of Technology)的報紙《科技人》(The Tech)在上周六凌晨報道了斯沃茨過世的消息。

斯沃茨的人生富於傳奇色彩,他曾從斯坦福大學(Stanford University)退學,創辦了多家公司和各種機構,還成了哈佛大學(Harvard University)埃德蒙·J·薩夫拉倫理研究中心(Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics)的研究員。

他成立的一家公司,最後與著名新聞和信息網站Reddit合并。他還參與創辦了針對社會公平問題發動網絡運動的“要求進步組織”(Demand Progress),該組織與其他組織共同發起了一次成功的運動,抵制好萊塢支持的一個網絡盜版法案。

他認為有些信息應該是人們能夠免費獲取的,但是,當他致力於向公眾發佈這些信息時,卻遇到了麻煩。2008年,他向法院電子檔案公共存取系統 (Public Access to Court Electronic Records,簡稱PACER,儲存聯邦司法文件的數據庫)發起了挑戰。

這個數據庫的文件每頁收費10美分(約合0.63元人民幣);一直以來,公共資源組織(public.resource.org)的創始人卡爾·馬 拉默德(Carl Malamud)等活動人士認為,這種文件應該是免費的,因為它們原本就是用公費創建的。馬拉默德為了公開這些文件,把通過合法手段獲取的文件放到網上免 費共享,而斯沃茨則編寫了一個簡潔的小程序,能夠讓用戶通過免費的圖書館賬戶下載2000萬頁文件,大概相當於那個巨大數據庫20%的內容。

政府強制關閉了免費的文庫程序,雖然馬拉默德並不認為他們違反了任何法律,但他還是擔心會惹上官司。他在一家報刊的報道中回憶道,“我當時立即感覺,法院有可能會做出過度反應。”他記得曾經告訴斯沃茨:“你必須找律師談談。我也要和律師談談。”

斯沃茨在2009年的採訪中回憶稱,“我預見到,聯邦政府工作人員將會破門而入,帶走一切。”他說,他把門上的栓子鎖好了,在床上躺了一會兒,之後打了個電話給母親。

聯邦政府對此事進行了調查,但沒有起訴。

但根據一份聯邦起訴書,2011年,斯沃茨的行動更進了一步。聯邦官員稱,為了使人們免費使用JSTOR,他入侵了麻省理工學院的計算機網絡,使用的手段包括進入校園內一個放置設備的柜子,並將一台以假名登錄校園網的手提電腦留在柜子里。

斯沃茨上交了他的幾個移動硬盤,其中有480萬份文件,不過JSTOR拒絕追究。但是一位美國聯邦檢察官卡門·M·奧爾蒂斯(Carmen M. Ortiz)卻不放棄,她說“偷竊就是偷竊,不管你用的是計算機指令還是一根撬棍,也無論你偷的是文件、數據還是錢。”

期刊存儲網JSTOR創建於1995年,是一個非營利組織,但機構可能需要支付數十萬美元訂閱,除了訂閱內容,訂戶還可以在線閱讀學術期刊。 JSTOR說,它需要這些錢來收集、傳播這些材料,有時還需要補貼付不起錢訂閱的機構。周三,JSTOR宣布,它將有限地開放1200份期刊檔案供大眾免 費閱讀。

馬拉默德說,雖然他不贊成斯沃茨在麻省理工學院的行為,“但如今,能否獲得知識和正義,完全取決於是否有錢,阿龍試圖改變這一現狀。他的這種行為不應該被視作犯罪。”

奎因·諾頓(Quinn Norton)是斯沃茨的一位密友。她說斯沃茨從未多談即將到來的那場審判,但每次他說到的時候,毫無疑問“這件事已讓他精疲力竭,超過了他的承受能力。”

諾頓說,斯沃茨近年來經歷種種困難。她說他“有時堅強有時脆弱”。“他患有痛苦的慢性病,還有抑鬱症,”她說,但沒有說明是何種疾病。但他“至少對這個世界”仍充滿希望。

在2007年的一次訪談中,斯沃茨描述了他在事業低谷時曾有自殺的念頭。他還寫到過如何與自己的抑鬱症鬥爭,他說這種病和悲傷不同。

“外出、呼吸新鮮空氣,或者擁抱愛人,都不會感到有一絲好轉,而只會感到更難受,因為無法體會到其他人所能感覺到的快樂。悲傷浸染了一切。”

他寫道,當情況惡化時,“你感到,彷彿一陣陣痛楚穿過你的頭。你劇烈地掙扎,你不停尋找出路,但卻找不到。而這還只是一種溫和的發作。”

斯沃茨的叔叔邁克爾·沃爾夫(Michael Wolf)說,26歲的斯沃茨應該是上吊自殺的。斯沃茨的一個朋友發現了他的屍體。

斯沃茨14歲的時候,就協助創造了“豐富站點摘要”(Rich Site Summary,簡稱RSS),這種工具幾乎無處不在,能夠讓用戶訂閱網絡信息。之後,他成了一名互聯網平民英雄,致力於使大量網絡文件成為免費公開的資 源。然而,2011年7月,聯邦政府指控他非法進入JSTOR(這是一個發佈科學和人文期刊的網站,只提供付費服務),並下載了480萬篇文章和文件,幾 乎是這個網絡圖書館的全部內容。

該案的指控包括電信欺詐和網絡欺詐。在斯沃茨死亡之時,這些指控尚未正式提出。他有可能面臨35年的監禁和100萬美元的罰款。

“阿龍創造的新技術令人驚訝,這些東西改變了信息在世界上的流通方式,”曾擔任奧巴馬政府科技顧問的紐約卡多佐法學院(Cardozo School of Law)教授蘇珊·克勞福德(Susan Crawford)說。她稱斯沃茨是個“難以捉摸的天才”,還說“計算機業的前輩們對他都會滿懷敬畏”。

沃爾夫說他會永遠銘記自己的侄子。過去,斯沃茨曾經寫下了與抑鬱和自殺想法作鬥爭的經歷。沃爾夫說,這個孩子“面對着這個世界,自己的大腦中存在一定的邏輯,而世界並不一定符合這個邏輯,所以這有時會很難。”

麻省理工學院(Massachusetts Institute of Technology)的報紙《科技人》(The Tech)在上周六凌晨報道了斯沃茨過世的消息。

斯沃茨的人生富於傳奇色彩,他曾從斯坦福大學(Stanford University)退學,創辦了多家公司和各種機構,還成了哈佛大學(Harvard University)埃德蒙·J·薩夫拉倫理研究中心(Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics)的研究員。

他成立的一家公司,最後與著名新聞和信息網站Reddit合并。他還參與創辦了針對社會公平問題發動網絡運動的“要求進步組織”(Demand Progress),該組織與其他組織共同發起了一次成功的運動,抵制好萊塢支持的一個網絡盜版法案。

他認為有些信息應該是人們能夠免費獲取的,但是,當他致力於向公眾發佈這些信息時,卻遇到了麻煩。2008年,他向法院電子檔案公共存取系統 (Public Access to Court Electronic Records,簡稱PACER,儲存聯邦司法文件的數據庫)發起了挑戰。

這個數據庫的文件每頁收費10美分(約合0.63元人民幣);一直以來,公共資源組織(public.resource.org)的創始人卡爾·馬 拉默德(Carl Malamud)等活動人士認為,這種文件應該是免費的,因為它們原本就是用公費創建的。馬拉默德為了公開這些文件,把通過合法手段獲取的文件放到網上免 費共享,而斯沃茨則編寫了一個簡潔的小程序,能夠讓用戶通過免費的圖書館賬戶下載2000萬頁文件,大概相當於那個巨大數據庫20%的內容。

政府強制關閉了免費的文庫程序,雖然馬拉默德並不認為他們違反了任何法律,但他還是擔心會惹上官司。他在一家報刊的報道中回憶道,“我當時立即感覺,法院有可能會做出過度反應。”他記得曾經告訴斯沃茨:“你必須找律師談談。我也要和律師談談。”

斯沃茨在2009年的採訪中回憶稱,“我預見到,聯邦政府工作人員將會破門而入,帶走一切。”他說,他把門上的栓子鎖好了,在床上躺了一會兒,之後打了個電話給母親。

聯邦政府對此事進行了調查,但沒有起訴。

但根據一份聯邦起訴書,2011年,斯沃茨的行動更進了一步。聯邦官員稱,為了使人們免費使用JSTOR,他入侵了麻省理工學院的計算機網絡,使用的手段包括進入校園內一個放置設備的柜子,並將一台以假名登錄校園網的手提電腦留在柜子里。

斯沃茨上交了他的幾個移動硬盤,其中有480萬份文件,不過JSTOR拒絕追究。但是一位美國聯邦檢察官卡門·M·奧爾蒂斯(Carmen M. Ortiz)卻不放棄,她說“偷竊就是偷竊,不管你用的是計算機指令還是一根撬棍,也無論你偷的是文件、數據還是錢。”

期刊存儲網JSTOR創建於1995年,是一個非營利組織,但機構可能需要支付數十萬美元訂閱,除了訂閱內容,訂戶還可以在線閱讀學術期刊。 JSTOR說,它需要這些錢來收集、傳播這些材料,有時還需要補貼付不起錢訂閱的機構。周三,JSTOR宣布,它將有限地開放1200份期刊檔案供大眾免 費閱讀。

馬拉默德說,雖然他不贊成斯沃茨在麻省理工學院的行為,“但如今,能否獲得知識和正義,完全取決於是否有錢,阿龍試圖改變這一現狀。他的這種行為不應該被視作犯罪。”

奎因·諾頓(Quinn Norton)是斯沃茨的一位密友。她說斯沃茨從未多談即將到來的那場審判,但每次他說到的時候,毫無疑問“這件事已讓他精疲力竭,超過了他的承受能力。”

諾頓說,斯沃茨近年來經歷種種困難。她說他“有時堅強有時脆弱”。“他患有痛苦的慢性病,還有抑鬱症,”她說,但沒有說明是何種疾病。但他“至少對這個世界”仍充滿希望。

在2007年的一次訪談中,斯沃茨描述了他在事業低谷時曾有自殺的念頭。他還寫到過如何與自己的抑鬱症鬥爭,他說這種病和悲傷不同。

“外出、呼吸新鮮空氣,或者擁抱愛人,都不會感到有一絲好轉,而只會感到更難受,因為無法體會到其他人所能感覺到的快樂。悲傷浸染了一切。”

他寫道,當情況惡化時,“你感到,彷彿一陣陣痛楚穿過你的頭。你劇烈地掙扎,你不停尋找出路,但卻找不到。而這還只是一種溫和的發作。”

Internet Activist, a Creator of RSS, Is Dead at 26, Apparently a Suicide

January 15, 2013

Aaron Swartz, a wizardly programmer who

as a teenager helped develop code that delivered ever-changing Web

content to users and who later became a steadfast crusader to make that

information freely available, was found dead on Friday in his New York

apartment.

An uncle, Michael Wolf, said that Mr. Swartz, 26, had apparently hanged himself, and that a friend of Mr. Swartz’s had discovered the body.

At 14, Mr. Swartz helped create RSS, the nearly ubiquitous tool that allows users to subscribe to online information. He later became an Internet folk hero, pushing to make many Web files free and open to the public. But in July 2011, he was indicted on federal charges of gaining illegal access to JSTOR, a subscription-only service for distributing scientific and literary journals, and downloading 4.8 million articles and documents, nearly the entire library.

Charges in the case, including wire fraud and computer fraud, were pending at the time of Mr. Swartz’s death, carrying potential penalties of up to 35 years in prison and $1 million in fines.

“Aaron built surprising new things that changed the flow of information around the world,” said Susan Crawford, a professor at the Cardozo School of Law in New York who served in the Obama administration as a technology adviser. She called Mr. Swartz “a complicated prodigy” and said “graybeards approached him with awe.”

Mr. Wolf said he would remember his nephew, who had written in the past about battling depression and suicidal thoughts, as a young man who “looked at the world, and had a certain logic in his brain, and the world didn’t necessarily fit in with that logic, and that was sometimes difficult.”

The Tech, a newspaper of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, reported Mr. Swartz’s death early Saturday.

Mr. Swartz led an often itinerant life that included dropping out of Stanford, forming companies and organizations, and becoming a fellow at Harvard University’s Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics.

He formed a company that merged with Reddit, the popular news and information site. He also co-founded Demand Progress, a group that promotes online campaigns on social justice issues — including a successful effort, with other groups, to oppose a Hollywood-backed Internet piracy bill.

But he also found trouble when he took part in efforts to release information to the public that he felt should be freely available. In 2008, he took on PACER, or Public Access to Court Electronic Records, the repository for federal judicial documents.

The database charges 10 cents a page for documents; activists like Carl Malamud, the founder of public.resource.org, have long argued that such documents should be free because they are produced at public expense. Joining Mr. Malamud’s efforts to make the documents public by posting legally obtained files to the Internet for free access, Mr. Swartz wrote an elegant little program to download 20 million pages of documents from free library accounts, or roughly 20 percent of the enormous database.

The government shut down the free library program, and Mr. Malamud feared that legal trouble might follow even though he felt they had violated no laws. As he recalled in a newspaper account, “I immediately saw the potential for overreaction by the courts.” He recalled telling Mr. Swartz: “You need to talk to a lawyer. I need to talk to a lawyer.”

Mr. Swartz recalled in a 2009 interview, “I had this vision of the feds crashing down the door, taking everything away.” He said he locked the deadbolt on his door, lay down on the bed for a while and then called his mother.

The federal government investigated but did not prosecute.

In 2011, however, Mr. Swartz went beyond that, according to a federal indictment. In an effort to provide free public access to JSTOR, he broke into computer networks at M.I.T. by means that included gaining entry to a utility closet on campus and leaving a laptop that signed into the university network under a false account, federal officials said.

Mr. Swartz turned over his hard drives with 4.8 million documents, and JSTOR declined to pursue the case. But Carmen M. Ortiz, a United States attorney, pressed on, saying that “stealing is stealing, whether you use a computer command or a crowbar, and whether you take documents, data or dollars.”

Founded in 1995, JSTOR, or Journal Storage, is nonprofit, but institutions can pay tens of thousands of dollars for a subscription that bundles scholarly publications online. JSTOR says it needs the money to collect and to distribute the material and, in some cases, subsidize institutions that cannot afford it. On Wednesday, JSTOR announced that it would open its archives for 1,200 journals to free reading by the public on a limited basis.

Mr. Malamud said that while he did not approve of Mr. Swartz’s actions at M.I.T., “access to knowledge and access to justice have become all about access to money, and Aaron tried to change that. That should never have been considered a criminal activity.”

Mr. Swartz did not talk much about his impending trial, Quinn Norton, a close friend, said on Saturday, but when he did, it was clear that “it pushed him to exhaustion. It pushed him beyond.”

Recent years had been hard for Mr. Swartz, Ms. Norton said, and she characterized him “in turns tough and delicate.” He had “struggled with chronic, painful illness as well as depression,” she said, without specifying the illness, but he was still hopeful “at least about the world.”

In a talk in 2007, Mr. Swartz described having had suicidal thoughts during a low period in his career. He also wrote about his struggle with depression, distinguishing it from sadness.

“Go outside and get some fresh air or cuddle with a loved one and you don’t feel any better, only more upset at being unable to feel the joy that everyone else seems to feel. Everything gets colored by the sadness.”

When the condition gets worse, he wrote, “you feel as if streaks of pain are running through your head, you thrash your body, you search for some escape but find none. And this is one of the more moderate forms.”

An uncle, Michael Wolf, said that Mr. Swartz, 26, had apparently hanged himself, and that a friend of Mr. Swartz’s had discovered the body.

At 14, Mr. Swartz helped create RSS, the nearly ubiquitous tool that allows users to subscribe to online information. He later became an Internet folk hero, pushing to make many Web files free and open to the public. But in July 2011, he was indicted on federal charges of gaining illegal access to JSTOR, a subscription-only service for distributing scientific and literary journals, and downloading 4.8 million articles and documents, nearly the entire library.

Charges in the case, including wire fraud and computer fraud, were pending at the time of Mr. Swartz’s death, carrying potential penalties of up to 35 years in prison and $1 million in fines.

“Aaron built surprising new things that changed the flow of information around the world,” said Susan Crawford, a professor at the Cardozo School of Law in New York who served in the Obama administration as a technology adviser. She called Mr. Swartz “a complicated prodigy” and said “graybeards approached him with awe.”

Mr. Wolf said he would remember his nephew, who had written in the past about battling depression and suicidal thoughts, as a young man who “looked at the world, and had a certain logic in his brain, and the world didn’t necessarily fit in with that logic, and that was sometimes difficult.”

The Tech, a newspaper of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, reported Mr. Swartz’s death early Saturday.

Mr. Swartz led an often itinerant life that included dropping out of Stanford, forming companies and organizations, and becoming a fellow at Harvard University’s Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics.

He formed a company that merged with Reddit, the popular news and information site. He also co-founded Demand Progress, a group that promotes online campaigns on social justice issues — including a successful effort, with other groups, to oppose a Hollywood-backed Internet piracy bill.

But he also found trouble when he took part in efforts to release information to the public that he felt should be freely available. In 2008, he took on PACER, or Public Access to Court Electronic Records, the repository for federal judicial documents.

The database charges 10 cents a page for documents; activists like Carl Malamud, the founder of public.resource.org, have long argued that such documents should be free because they are produced at public expense. Joining Mr. Malamud’s efforts to make the documents public by posting legally obtained files to the Internet for free access, Mr. Swartz wrote an elegant little program to download 20 million pages of documents from free library accounts, or roughly 20 percent of the enormous database.

The government shut down the free library program, and Mr. Malamud feared that legal trouble might follow even though he felt they had violated no laws. As he recalled in a newspaper account, “I immediately saw the potential for overreaction by the courts.” He recalled telling Mr. Swartz: “You need to talk to a lawyer. I need to talk to a lawyer.”

Mr. Swartz recalled in a 2009 interview, “I had this vision of the feds crashing down the door, taking everything away.” He said he locked the deadbolt on his door, lay down on the bed for a while and then called his mother.

The federal government investigated but did not prosecute.

In 2011, however, Mr. Swartz went beyond that, according to a federal indictment. In an effort to provide free public access to JSTOR, he broke into computer networks at M.I.T. by means that included gaining entry to a utility closet on campus and leaving a laptop that signed into the university network under a false account, federal officials said.

Mr. Swartz turned over his hard drives with 4.8 million documents, and JSTOR declined to pursue the case. But Carmen M. Ortiz, a United States attorney, pressed on, saying that “stealing is stealing, whether you use a computer command or a crowbar, and whether you take documents, data or dollars.”

Founded in 1995, JSTOR, or Journal Storage, is nonprofit, but institutions can pay tens of thousands of dollars for a subscription that bundles scholarly publications online. JSTOR says it needs the money to collect and to distribute the material and, in some cases, subsidize institutions that cannot afford it. On Wednesday, JSTOR announced that it would open its archives for 1,200 journals to free reading by the public on a limited basis.

Mr. Malamud said that while he did not approve of Mr. Swartz’s actions at M.I.T., “access to knowledge and access to justice have become all about access to money, and Aaron tried to change that. That should never have been considered a criminal activity.”

Mr. Swartz did not talk much about his impending trial, Quinn Norton, a close friend, said on Saturday, but when he did, it was clear that “it pushed him to exhaustion. It pushed him beyond.”

Recent years had been hard for Mr. Swartz, Ms. Norton said, and she characterized him “in turns tough and delicate.” He had “struggled with chronic, painful illness as well as depression,” she said, without specifying the illness, but he was still hopeful “at least about the world.”

In a talk in 2007, Mr. Swartz described having had suicidal thoughts during a low period in his career. He also wrote about his struggle with depression, distinguishing it from sadness.

“Go outside and get some fresh air or cuddle with a loved one and you don’t feel any better, only more upset at being unable to feel the joy that everyone else seems to feel. Everything gets colored by the sadness.”

When the condition gets worse, he wrote, “you feel as if streaks of pain are running through your head, you thrash your body, you search for some escape but find none. And this is one of the more moderate forms.”

-----

很久沒去潘震澤老師的 blog

讀了簡介 Rosalyn S. Yalow

http://blog.chinatimes.com/jenntser/archive/2011/06/08/704404.html

一下子就可找到提到的悼文 (紐約時報)

Rosalyn S. Yalow, Nobel Medical Physicist, Dies at 89

By DENISE GELLENE

Published: June 1, 2011

Rosalyn S. Yalow, a medical physicist who persisted in entering a field largely reserved for men to become only the second woman to earn a Nobel Prize in Medicine, died on Monday in the Bronx, where she had lived most of her life. She was 89.

Rosalyn S. Yalow and Sol Berson in Pittsburgh with a check they won from the Universtiy of Pittsburgh.

Dr. Yalow, a product of New York City schools and the daughter of parents who never finished high school, graduated magna cum laude from Hunter College in New York at the age of 19 and was the college’s first physics major. Yet she struggled to be accepted for graduate studies. In one instance, a skeptical Midwestern university wrote: “She is from New York. She is Jewish. She is a woman.”

Undeterred, she went on to carve out a renowned career in medical research, largely at a Bronx veterans hospital, and in the 1950s became a co-discoverer of the radioimmunoassay, an extremely sensitive way to measure insulin and other hormones in the blood. The technique invigorated the field of endrocrinology, making possible major advances in diabetes research and in diagnosing and treating hormonal problems related to growth, thyroid function and fertility.

The test is used, for example, to prevent mental retardation in babies with underactive thyroid glands. No symptoms are present until a baby is more than 3 months old, too late to prevent brain damage. But a few drops of blood from a pinprick on the newborn’s heel can be analyzed with radioimmunoassay to identify babies at risk.

The technique “brought a revolution in biological and medical research,” the Karolinska Institute in Sweden said in awarding Dr. Yalow the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1977.

“We are witnessing the birth of a new era of endocrinology, one that started with Yalow,” the institute said.

Dr. Yalow developed radioimmunoassay with her longtime collaborator, Dr. Solomon A. Berson. Their work challenged what was then accepted wisdom about the immune system; skeptical medical journals initially refused to publish their findings unless they were modified.

Dr. Berson died in 1972, before Dr. Yalow was honored with the Nobel. The institute does not make awards posthumously. Dr. Yalow was the second woman to win the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. The first, in 1947, was Gerty Theresa Cori, an American born in Prague. Dr. Yalow shared her Nobel with two other scientists for unrelated research. (Eight more women have won the medicine prize since then.)

Rosalyn Sussman was born in the South Bronx on July 19, 1921. Her father, Simon Sussman, who had moved from the Lower East Side of Manhattan to the Bronx, was a wholesaler of packaging materials; her mother, the former Clara Zipper, who was born in Germany, was a homemaker.

Dr. Yalow told interviewers that she had known from the time she was 8 years old that she wanted to be a scientist in an era when women were all but prohibited from science careers. She loved the logic of science and its ability to explain the natural world, she said.

At Walton High School in the Bronx, she wrote, a “great” teacher had excited her interest in chemistry. (She was one of two Walton graduates, both women, to earn a Nobel in medicine, the other being Gertrude Elion, in 1988. Walton was closed in 2008 as a failing school.) Her interests gravitated to physics after she read Eve Curie’s 1937 biography of her mother, Marie Curie, a two-time Nobel laureate for her research on radioactivity.

Nuclear physics “was the most exciting field in the world,” Dr. Yalow wrote in her official Nobel autobiography. “It seemed as if every major experiment brought a Nobel Prize.”

She went on to Hunter College, becoming its first physics major and graduating with high honors at only 19. After she applied to Purdue University for a graduate assistantship to study physics, the university wrote back to her professor: “She is from New York. She is Jewish. She is a woman. If you can guarantee her a job afterward, we’ll give her an assistantship.”

No guarantee was possible, and the rejection hurt, Dr. Yalow told an interviewer. “They told me that as a woman, I’d never get into graduate school in physics,” she said, “so they got me a job as a secretary at the College of Physicians and Surgeons and promised that, if I were a good girl, I would take courses there.” The college is part of Columbia University.

World War II and the draft were creating academic opportunities for women; to her delight, Dr. Yalow was awarded a teaching assistantship at the College of Engineering at the University of Illinois. She tore up her steno books and headed to Champaign-Urbana, becoming the first woman to join the engineering school’s faculty in 24 years.

As the only woman among 400 teaching fellows and faculty members, however, she faced more than the usual pressure to prove herself. When she received an A-minus in one laboratory course, the chairman of the physics department at Illinois said the grade confirmed that women could not excel at lab work; the slight fueled her determination.

She married a fellow graduate student, Aaron Yalow, in 1943. He died in 1992. Besides her son, Benjamin, of the Bronx, she is survived by her daughter, Elanna Yalow of Larkspur, Calif., and two grandchildren.

Dr. Yalow received her doctorate in nuclear physics in 1945, and went to teach at Hunter College the following year. When she could not find a research position, she volunteered to work in a medical lab at Columbia University, where she was introduced to the new field of radiotherapy. She moved to the Bronx Veterans Administration Hospital, now the James J. Peters Veterans Affairs Medical Center, as a part-time researcher in 1947 and began working full time in 1950. That same year, she began her 22-year collaboration with Dr. Berson.

Dr. Berson was seen as the dominant partner. By virtue of his gender and medical degree, he had more contacts with journals, professional societies and in academia. Dr. Yalow was single-mindedly focused on her research; for much of her professional life, she lived in a modest house in the Bronx less than one mile from the hospital. She had no hobbies and traveled only to give lectures and attend conferences.

In their work on radioimmunoassay, Dr. Yalow and Dr. Berson used radioactive tracers to measure hormones that were otherwise difficult or impossible to detect because they occur in extremely low concentrations. They went on to use the test to measure concentrations of vitamins, viruses and other substances in the body. Today the test has been largely supplanted by a technique that does not use radioactivity.

Their early work met with resistance. Scientific journals initially refused to publish their discovery of insulin antibodies, a finding fundamental to radioimmunoassay. The discovery, in 1956, challenged the accepted understanding of the immune system; few scientists believed antibodies could recognize a molecule as small as insulin. Dr. Yalow and Dr. Berson had to delete a reference to antibodies before The Journal of Clinical Investigation accepted their paper, and Dr. Yalow did not forget the incident; she included the rejection letter as an exhibit in her Nobel lecture.

With Dr. Berson, Dr. Yalow made other discoveries. Using radioimmunoassay, she determined that people with Type 2 diabetes produced more insulin than non-diabetics, providing early evidence that an inability to use insulin caused diabetes. Researchers in her lab at the Bronx veterans hospital modified radioimmunoassay to detect other hormones, vitamin B12 and the hepatitis B virus. The latter adaptation allowed blood banks to screen donated blood for the virus.

Dr. Berson’s death affected Dr. Yalow deeply; she named her lab in his honor so his name would continue to appear on her published research.

She was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1975 and received the Albert Lasker Medical Research Award, often a precursor to the Nobel, in 1976. At her death, she was senior medical investigator emeritus at the Bronx veterans medical center and the Solomon A. Berson distinguished professor-at-large at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York.

Five years after she received the Nobel, Dr. Yalow spoke to a group of schoolchildren about the challenges and opportunities of a life in science. “Initially, new ideas are rejected,” she told the youngsters. “Later they become dogma, if you’re right. And if you’re really lucky you can publish your rejections as part of your Nobel presentation.”

沒有留言:

張貼留言

注意:只有此網誌的成員可以留言。