“Nothing is as dangerous in architecture as dealing with separated problems. If we split life into separated problems we split the possibilities to make good building art.” Alvar Aalto

#architecture #design #problemsolving #innovation #creativity #art #AlvarAalto #integrateddesign #possibilities #buildingart

*****

Design Icons | 24 September 2013

Why the ‘Barcelona’ Pavilion is a modernist classic

HIDE CAPTION

- National pride

- The German Pavilion was commissioned to represent Germany at the 1929 International Exhibition in Barcelona. (Corbis)

Mies van der Rohe’s German Pavilion in Barcelona is one of the most

influential modernist buildings of the 20th Century, argues Jonathan

Glancey.

For more than half a century, the ‘Barcelona Pavilion’ haunted the imagination of modern architects worldwide. Here was one of the most enticing, beautiful and refined buildings of all time, and yet it had stood for no more than a few months before it was pulled down. All that was left, from 1930, of this exquisite structure by the great German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886-1969) were drawings and photographs.

Even then, these were enough to inspire imperfect lookalike designs over several decades in the guise of new houses and art galleries. The reason this beautiful pavilion with its geometric arrangement of shimmering glass and marble planes – its slimline roof supported by eight of the slenderest chromed-steel columns– had been so short lived was that it had been nothing more, if nothing less, than a temporary exhibition space.

Set high on Montjuic, a hill overlooking the harbour of Barcelona, the pavilion was visited by hundreds of thousands of people. It was commissioned by the Weimar Republic; and its job was to advertise a new, progressive, democratic and modern Germany, a decade on from the Treaty of Versailles and the carnage of World War I. And, yet, this vision of the future was no starkly functional ‘machine for living’. No: the German Pavilion, to give Mies’s 1929 triumph its proper name, was realised in rich and stunning materials: four shades of tinted glass, along with marble, onyx, chromed steel and travertine.

travertine

- 音節

- trav • er • tine

- 発音

- trǽvərtìːn

onyx

- 音節

- on • yx

- 発音

- ɑ'niks | ɔ'n-

- onyxの変化形

- onyxes (複数形)

[名]

1 [U][C]《宝石》縞瑪瑙(しまめのう), オニキス.

2 [U]黒色.

━━[形]黒い, 漆黒の.Out of this world

Set on a travertine plinth, its gleaming, offset walls created subtle spatial illusions enhanced by sunlight, and moonlight, shimmering and sparkling from both the rich building materials and from the rectangular pool that permeated the structure. Walking through the pavilion, with reflections of sun-dappled water playing on the underside of the roof, and breezes wafting through open walls, it was hard to tell interior from exterior. It was built quickly, as you expect of an exhibition stand, and yet the quality of the materials Mies chose meant that the German Pavilion looked as if it would last for decades rather than months. The roof – a thin plane of concrete render over steel – appeared to float over the structure, creating the extraordinary effect of a building that was at once substantial and ethereal.

This dreamlike sensation was reinforced by the fact that there was nothing to see inside beyond the architecture itself, save for a single sculpture of a female nude - Alba, or Dawn, by the German artist George Kolbe - and the architect’s new leather and chrome steel Barcelona chairs. While other nations worked hard to show what they were made of through rich and eclectic displays of art and design, Weimar Germany chose to represent itself through this minimalist and ethereal pavilion alone.

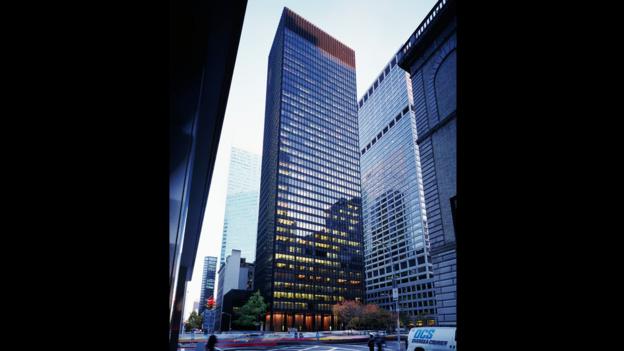

Master builder

Mies went on to great heights. Alongside Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright and Alvar Aalto, he has long been considered one of the masters of 20th Century Modern architecture. Germany, however, was under Nazi rule within just three years of the closure of the 1929 Barcelona Expo. Despite trying to win commissions, Mies was considered anathema by the new regime. The last principal of the Bauhaus – closed, under government pressure, in 1933 – he went to the Institute of Technology (ITT), Chicago, four years later, where he created a school of thought and design. A US citizen from 1944, he produced such magnificent buildings as the seemingly timeless bronze-clad Seagram Tower (1958) on New York’s Park Avenue. His cool, rational architecture – “less is more” he said, famously – was adopted by young modern architects worldwide, initially perhaps for the better, but as the quality dropped with quantity, for the worse. Less had become a bore.

The memory of the Barcelona Pavilion, however, lived on. It had demonstrated how beautiful and lyrical modern architecture could be. And, as modernism came increasingly under attack in the 1970s and 80s – accused of ugliness and even brutality – the aesthetic and cultural value of the pavilion only grew. In 1983, the Fundacio Mies van der Rohe was set up in Barcelona with the aim of recreating the legendary pavilion. Compelling, captivating and utterly enchanting, the replica opened in 1986. And, partly as a result, there was indeed a revival of purist modernism in Europe and the United States in the late Eighties and through the following decade.

Nothing, though - no prince, no planning authority, no public inquiry – could ever deny the beauty of, nor dent the reputation of the Barcelona Pavilion. Today, the perfect replica is open to the public everyday, a design as exquisite in its own modern way as a Greek temple, and so very happily sited in what – certainly in terms of architecture, design and urban planning – is, by common consent, one of the world’s greatest cities.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

沒有留言:

張貼留言

注意:只有此網誌的成員可以留言。