http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tony_Benn

Tony Benn, veteran Labour politician, dies aged 88

Former cabinet minister dies at his home in west London surrounded by family members

Tributes poured in for one the country's most extraordinary and controversial MPs, who, in what he described as the blazing autumn of his career outside Westminster, came to be regarded as an anti-establishment voice for democracy.

Although he said self-deprecatingly in one of his later interviews: "All political careers end in failure; mine just happened to end earlier than most," many regarded his final decades outside Westminster with greatest affection.

In a statement, his children Stephen, Hilary, Melissa and Joshua said: "It is with great sadness that we announce that our father Tony Benn died peacefully early this morning at his home in west London surrounded by his family.

"We would like to express our heartfelt thanks to all the NHS staff and carers who have looked after him with such kindness in hospital and at home.

"We will miss above all his love which has sustained us throughout our lives. But we are comforted by the memory of his long, full and inspiring life and so proud of his devotion to helping others as he sought to change the world for the better. Arrangements for his funeral will be announced in due course."

Tony Benn had suffered from ill health since a stroke in 2012. Photograph: David Levene

Born Anthony Neil Wedgwood Benn, he entered parliament in 1950 as MP

for Bristol South East, becoming the youngest member of the house at the

age of 25.

Tony Benn had suffered from ill health since a stroke in 2012. Photograph: David Levene

Born Anthony Neil Wedgwood Benn, he entered parliament in 1950 as MP

for Bristol South East, becoming the youngest member of the house at the

age of 25.He had to leave the Commons a decade later, as the death of his father, a Labour peer, meant he inherited the title of Viscount Stansgate. However, he campaigned for a change in the law and returned to his seat three years later after renouncing the title.

During his 50-year parliamentary career, Benn served as minister for technology, industry and energy under Harold Wilson and James Callaghan. He also campaigned against EU membership and oversaw the development of Concorde.

After a successful cabinet career under Wilson in the 70s, he swung to the left politically and challenged Denis Healey for the Labour deputy leadership – only losing by the narrowest of margins after one of the key unions switched sides at the last minute.

He then became instrumental in using Labour party machinery to develop a leftwing manifesto on which Michael Foot fought the 1983 election.

He was also central to the campaign to make Labour MPs more accountable to their constituencies through automatic re-selection, a reform hated by many Labour MPs at the time but now regarded as wholly uncontroversial.

After Foot's defeat and the emergence of Neil Kinnock as party leader in 1983, the party shifted to the centre, and Benn began to lose his direct political influence over the party. He was heavily defeated when he stood against Kinnock for the party leadership in 1988 and left parliament in 2001, after the first term of the Blair government, to "spend more time on politics".

From there on his influence tended to emerge through his thinking, diaries, oratory and latterly appearances at literary festivals and political rallies.

Benn was a divisive figure within the Labour party because of his

steadfast support for traditional socialism. Photograph: Christopher

Furlong/Getty Images

He became known for his campaign against the invasion of Iraq,

addressing the UK's biggest ever demonstration during the Stop the War

rally of 2003.

Benn was a divisive figure within the Labour party because of his

steadfast support for traditional socialism. Photograph: Christopher

Furlong/Getty Images

He became known for his campaign against the invasion of Iraq,

addressing the UK's biggest ever demonstration during the Stop the War

rally of 2003.Ed Miliband, the Labour leader, said: "The death of Tony Benn represents the loss of an iconic figure of our age. He will be remembered as a champion of the powerless, a great parliamentarian and a conviction politician.

"Tony Benn spoke his mind and spoke up for his values. Whether you agreed with him or disagreed with him, everyone knew where he stood and what he stood for.

"For someone of such strong views, often at odds with his party, he won respect from across the political spectrum.

"This was because of his unshakeable beliefs and his abiding determination that power and the powerful should be held to account."

Tony Benn at Labour conference in Brighton in October 1979. Photograph: Evening Standard/Getty Images

Miliband said he had done work experience with Benn at the age of 16.

"I may have been just a teenager but he treated me as an equal," the

Labour leader said.

Tony Benn at Labour conference in Brighton in October 1979. Photograph: Evening Standard/Getty Images

Miliband said he had done work experience with Benn at the age of 16.

"I may have been just a teenager but he treated me as an equal," the

Labour leader said.Margaret Beckett, a contemporary during some of the most bitter Labour infighting in the 80s said: "He was an absolutely brilliant speaker ... he had such clarity of expression." She added that he was "a charming, nice man. He made enemies and kept enemies but on the whole most people regarded him with a good degree of affection long before it came to the stage when it was thought he could cause no harm. He was out of step for many years with whoever was in the charge of the leadership. He wanted to make people think and that was an admirable thing."

David Cameron – who once said he had been strongly influenced by Benn's book Arguments for Democracy – tweeted: "Tony Benn was a magnificent writer, speaker and campaigner. There was never a dull moment listening to him, even if you disagreed with him."

The former Labour cabinet minister Peter Hain said: "Tony Benn was a giant of socialism who encouraged me to join Labour in 1977: wonderful inspirational speaker and person: will be deeply missed."

The Labour MP for Hackney North and Stoke Newington, Diane Abbott, also paid tribute to Benn. "Admired so many things about Benn," she said. "Unwavering principles; always open to new ideas; stellar political speaker but unfailingly courteous."

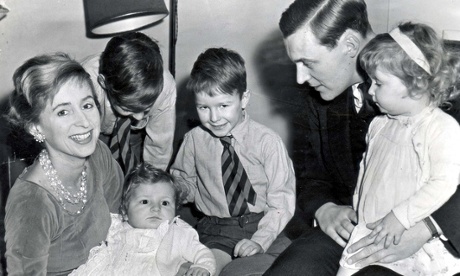

Tony Benn with his wife Caroline, children Stephen, Hilary, Melissa,

and new baby Joshua. Photograph: Evening News / Rex Features

Shami Chakrabarti, director of Liberty, said: "In the final decade of

an extraordinary political life, Tony Benn was a great friend of

Liberty and human rights. He spoke to packed audiences up and down the

country against internment and identity cards and for values of

internationalism and humanity. And he often shared the stage with

speakers of different political stripes with considerable generosity. I

shall never forget his many kindnesses to me, including when he ripped

up a prepared speech he was about to deliver, in order to make my own

nervous and novice remarks sound slightly less unplanned. In an age of

spin, he was solid, a signpost and not a weathervane."

Tony Benn with his wife Caroline, children Stephen, Hilary, Melissa,

and new baby Joshua. Photograph: Evening News / Rex Features

Shami Chakrabarti, director of Liberty, said: "In the final decade of

an extraordinary political life, Tony Benn was a great friend of

Liberty and human rights. He spoke to packed audiences up and down the

country against internment and identity cards and for values of

internationalism and humanity. And he often shared the stage with

speakers of different political stripes with considerable generosity. I

shall never forget his many kindnesses to me, including when he ripped

up a prepared speech he was about to deliver, in order to make my own

nervous and novice remarks sound slightly less unplanned. In an age of

spin, he was solid, a signpost and not a weathervane."Benn was a divisive figure within the Labour party because of his steadfast support for traditional socialism. His son Hilary, the Labour MP for Leeds Central and shadow secretary of state for communities and local government, famously described himself as "a Benn, not a Bennite". The Sun once asked whether his firebrand views made him "the most dangerous man in Britain".

Some old ministerial colleagues from the 1970s and 80s privately made plain they would be making no public comment, reluctant to speak ill of the dead. But bitterness against what they still see as his destructive and dishonest conduct during the Bennite ascendancy remains toxic.

His death prompted tributes from many Eurosceptic MPs who remembered his longstanding opposition to the European Union.

Benn had suffered from ill health since a stroke in 2012, spending much of the subsequent year in hospital. In an interview with the Daily Mirror last year, he said he was not frightened about death. "I don't know why, but I just feel that at a certain moment your switch is switched off and that's it. And you can't do anything about it," he said.

Benn was admitted to hospital again in September last year on the advice of his GP after feeling unwell and had recently moved to sheltered accommodation near his Holland Park home in west London.

Outside his home in his garden stands the bench on which he proposed to Caroline, the wife he was devoted to and whom he missed grievously after her death. He is survived by their four children, Stephen, Hilary, Melissa and Joshua.

*****

Tony Benn

Anthony Wedgwood Benn, spear-thrower of the British left, died on March 14th, aged 88

That direction was socialist. Not socialism as professed by the Labour Party, in which there were too few socialists and too many kings of the Tony Blair variety; in which the people were not represented, but managed; and in which, far from changing society, the government tried to change the people to fit the status quo. Mr Benn belonged to the Labour movement, broad-based and active; not to the party, elitist and more or less ossified.

True, he’d served 51 years in the party, as an MP for Bristol South-East and Chesterfield. He had had to fight to sit in the Commons at all, campaigning for eight years to renounce the peerage he had inherited from his father. He had been a minister, for industry and later for energy, under Harold Wilson and Jim Callaghan in the 1970s: right-wing governments both, in his view, though Labour in name. So his industry bill, demanding more state planning and nationalisation, was dead on arrival in 1975; and he was never elected to the party leadership because his opponents inexplicably disliked his programme of disarmament, import controls, a wealth tax, and the handing of more political power to militant shop stewards.

Many said he had wrecked the Labour Party, which in 1979 lost power for a generation. Mr Benn thought that nonsense. The party leaders had wrecked it by losing touch with the people. They might even have gone into the Common Market without popular consent, had he not insisted on a referendum in 1975 (in which, dismayingly and despite his untiring “No” campaign, the people voted “Yes”). Labour leaders had sold out to Europe, NATO and the IMF—just as Mr Blair sold out later to the warmongering Americans. He would never do so; because though most leaders were unprincipled weathercocks, he was one of the few unbending signposts, pointing (as Margaret Thatcher had also, but wrongly, pointed) to the promised land.

The route he preached was “pure” socialism. Not the Marxist sort, though he fell out often with the party over clause four of its constitution, which committed the party to nationalising the means of production, distribution and exchange; though he scorned the free market New Labour so hotly embraced, and found global capitalism disgusting. No, he meant socialism in the tradition of the Peasants’ Revolt, the Tolpuddle Martyrs and the Chartists, campaigners for the rights of the working man. All progress came from underneath.

The tea-powered megaphone

Mr Benn was really a Leveller, the 17th-century group who rejected

all authority and preached absolute equality. He was not merely a

republican who, like Cromwell, fought to get the royal head removed

(from Britain’s stamps, when he was postmaster-general). He was also

sceptical about parliamentary democracy itself. Power was only on loan

to Parliament from the people; therefore, most MPs being useless, it was

better if the people ran things themselves. Hence his indulgence of

Trotskyites and rabble-rousers in the unions; his eagerness to prop up

Britain’s heavy industries, mostly in vain, with workers’ co-operatives;

and his hatred (he was a good hater) of those who seemed to stand in

the way.Where did this drive to be difficult come from? Not his happily middle-class family life, though Liberal-Labour politics had filtered through from his father, and non-conformist piety (altered by him to humanism) from his mother. Not from fee-paying Westminster school, where he wore top hat and tails, an attendance he excised from his entry in “Who’s Who”. But his battle to take his Commons seat, with his local constituents pitted against the Establishment, committed him to people-power. And the death of his elder brother on active service in 1944 filled him with such deep and abiding hatred of war that he even visited Saddam Hussein to divert, single-handed, the American invasion.

His campaign for a better world was generally conducted alone. After the late 1970s (when he mustered a band of Jacobins around him) he seemed to need no faction, having enough tea-fuelled energy for several men. Enemies were everywhere, of course. The Murdoch-and-Maxwell press called him bonkers for years. The Thought Police were out to get him. MI5 went through his rubbish. Nonetheless the books kept appearing and, well into old age, Mr Benn himself, plummily eloquent as ever through pipe, microphone or megaphone. No, not a treasure, but worth protecting all the same, as a curiously resilient artefact from Labour’s misspent past.

沒有留言:

張貼留言

注意:只有此網誌的成員可以留言。