High quality global journalism requires investment. Please share this article with others using the link below, do not cut & paste the article. See our Ts&Cs and Copyright Policy for more detail. Email ftsales.support@ft.com to buy additional rights. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/67b8f490-4269-11e4-9818-00144feabdc0.html#ixzz3EW8PGXwW

September 26, 2014 12:51 pm

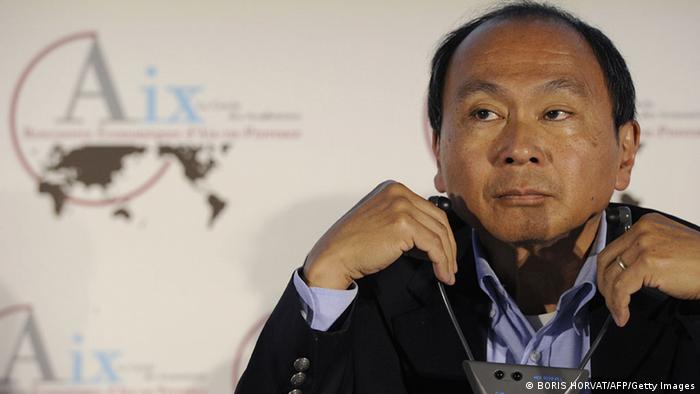

Francis Fukuyama’s ‘Political Order and Political Decay’

The triumph of liberal freedoms looks far from assured in this grand survey of political change since the Industrial Revolution – and the US is no exception

Political Order and Political Decay: From the Industrial Revolution to the Globalisation of Democracy, by Francis Fukuyama, Profile, RRP£25/ Farrar, Straus and Giroux, RRP$35, 672 pages

It is not often that a 600-page work of political science ends with a cliffhanger. But the first volume of Francis Fukuyama’s epic two-part account of what makes political societies work, published three years ago, left the big question unanswered. That book took the story of political order from prehistoric times to the dawn of modern democracy in the aftermath of the French Revolution. Fukuyama is still best known as the man who announced in 1989 that the birth of liberal democracy represented the end of history: there were simply no better ideas available. But here he hinted that liberal democracies were not immune to the pattern of stagnation and decay that afflicted all other political societies. They too might need to be replaced by something better. So which was it: are our current political arrangements part of the solution, or part of the problem?

The explosive growth in industrial capacity and wealth that the world has experienced in the past 200 years has vastly expanded the range of political possibilities available, for better and for worse (just look at the terrifying gap between the world’s best functioning societies – such as Denmark – and the worst – such as the Democratic Republic of Congo). There are now multiple different ways state capacity, legal systems and forms of government can interact with each other, and in an age of globalisation multiple different ways states can interact with each other as well. Modernity has speeded up the process of political development and it has complicated it. It has just not made it any easier.

What matters most of all is getting the sequence right. Democracy doesn’t come first. A strong state does. States that democratise before they acquire the capacity to rule effectively will invariably fail. This is what has gone wrong in many parts of Africa. Democracy has exacerbated existing failings rather than correcting for them because it eats away at the capacity of government to exert its authority, by subjecting it to too many conflicting demands. By contrast, in east Asia – in places such as Japan and South Korea – a tradition of strong central government preceded democracy, which meant the state could survive the empowerment of the people.

This is an explanation of how we have got to where we are but it is not a recipe for making the world a better place. Telling people who want democracy to hold off in order to strengthen their state won’t wash, because having to live under a strong state in the absence of democracy is often a miserable experience: that’s why the Arab spring erupted in the first place. It is the basic tension in Fukuyama’s oeuvre: if we live in an age where democracy is the best idea but discover that democracy will only work if we defer it, then politics is going to be a horribly messy business.

A widespread attempt to achieve leaner and more efficient government has only succeeded in bloating it and making it more bureaucratically oppressive

The other problem is that getting the right sequence often takes a shock to the system. War remains the great engine of political development because it can empower the state, so making it fit for democracy once the fighting is over. This is what happened in the aftermath of the first and second world wars. Peace comes at a price, however. Fukuyama argues that Latin American politics is often so dysfunctional because that continent has been spared the worst of global conflict. Fewer wars meant weaker states and weaker states means political instability. It doesn’t follow that violence always helps, though – the wrong kind of violence can be even worse than no violence at all. Colonial rule in Africa was bloody but it was also destabilising because the imperial powers used violence as a substitute for building local administrative capacity. That pattern has repeated itself today in Afghanistan and Iraq. Peace is dangerous and war is hell. There are few consolations in this story.

. . .

Fukuyama’s analysis provides a neat checklist for assessing the political health of the world’s rising powers. India, for instance, thanks to its colonial history, has the rule of law (albeit bureaucratic and inefficient) and democratic accountability (albeit chaotic and cumbersome) but the authority of its central state is relatively weak (something Narendra Modi is trying to change). Two out of three isn’t bad, but it’s far from being a done deal. China, by contrast, thanks to its own history as an imperial power, has a strong central state (dating back thousands of years) but relatively weak legal and democratic accountability. Its score is more like one and a half out of three, though it has the advantage that the sequence is the right way round were it to choose to democratise. Fukuyama doesn’t say if it will or it won’t – the present signs are not encouraging – but the possibility remains open.

The really interesting case study, however, is the US. America’s success over the past 200 years bucks the trend of Fukuyama’s story because the sequence was wrong: the country was a democracy long before it had a central state with any real authority. It took a civil war to change that, plus decades of hard-fought reform. Among the heroes of Fukuyama’s book are the late-19th and early-20th-century American progressives who dragged the US into the modern age by giving it a workable bureaucracy, tax system and federal infrastructure. On this account, Teddy Roosevelt is as much the father of his nation as Washington or Lincoln.

But even this story doesn’t have a happy ending. Just as it can take a major shock to achieve political order, so in the absence of shocks a well-ordered political society can get stuck. That is what has happened to the US. In the long peace since the end of the second world war (and the shorter but deeper peace since the end of the cold war), American society has drifted back towards a condition of relative ungovernability. Its historic faults have come back to haunt it. American politics is what Fukuyama calls a system of “courts and parties”: legal and democratic redress are valued more than administrative competence. Without some external trigger to reinvigorate state power (war with China?), partisanship and legalistic wrangling will continue to corrode it. Meanwhile, the US is also suffering the curse of all stable societies: capture by elites. Fukuyama’s ugly word for this is “repatrimonialisation”. It means that small groups and networks – families, corporations, select universities – use their inside knowledge of how power works to work it to their own advantage. It might sound like social science jargon, but it’s all too real: if the next presidential election is Clinton v Bush again we’ll see it happening right before our eyes.

True political stability comes when the positive and negative sides of democracy cohere: when people who control the power of their governments also come to value them

Fukuyama is keen to emphasise that a strong state doesn’t have to mean a large one: he tries not to take sides in the argument between the proponents of big and small government. Stable societies can operate with a lean welfare system (Singapore) as well as a far more extensive one (the Netherlands). But his argument does have one counterintuitive insight that is deeply pertinent to our present democratic discontents. If strong central authority is needed to make politics work, then even people who want to shrink the state need to be careful they don’t shrink its capacity to govern at the same time. This is the paradox of mature political development: if you want a less controlling state you need strong state control to achieve it. Otherwise you get what has been happening in the US (and to a lesser extent in Britain) over the past generation: a widespread attempt to achieve leaner and more efficient government has only succeeded in bloating it and making it more bureaucratically oppressive. The only thing that can rein in the state is a more powerful state. The politics of austerity is a very precarious balancing act.

So what happened to the end of history? At the heart of this book is a tension that Fukuyama never quite resolves between democracy as a positive value and democracy as a negative one. The positive value is dignity: people who rule themselves have a greater sense of self-worth. The negative value is constraint: people who rule themselves have far greater opportunities to complain about governments they don’t like. True political stability comes when the positive and negative sides of democracy cohere: when people who control the power of their governments also come to value them. That is not true at present. Where democracy has come to mean dignity – in Egypt, for example – constraint is chaotic and counter-productive. Where constraint is fully functional – as in the US – dignity is in short supply. In its place is a politics of resentment and complaint, manifested as deep-seated partisan intolerance. Fukuyama points out the irony that the US institutions that currently poll best with the American people – the armed forces, Nasa – are the ones that experience the least democratic oversight. The institutions Americans really hate – such as Congress – are the ones they control themselves.

This book offers the best account I have read of how we reached this point. Its slightly flat academic style hides a wealth of insights worthy of the greatest writers about democracy. It is not all doom and gloom. Fukuyama retains faith in the capacity of smart leaders to find a path out of the cave. He insists that geography is not destiny and history is not fate. Countries continue to do well or badly according to the political choices they make. Costa Rica is a relative success story because during the 20th century its politicians got the big decisions right. Argentina has squandered many of its advantages because its politicians got them wrong. All this takes time to play out, however. Even the US needed the best part of a century to get its house in order. And time may no longer be on anyone’s side.

The pace of technological change along with rising ecological risks means that the shocks will keep coming, though it’s far from clear that states will acquire the capacity to deal with them. Twenty-first-century wars – such as the one against Isis that is just getting going – are increasingly bitty and piecemeal, fought at one remove by drones and proxy armies. They are as likely to erode government authority as to enhance it. The politics of complaint is on the rise almost everywhere. In a coda to the 1989 essay that made him an intellectual superstar, Fukuyama wrote that “the end of history will be a very sad time”. He was more right than he knew.

David Runciman is professor of politics at Cambridge university and author of ‘The Confidence Trap: A History of Democracy in Crisis from World War I to the Present’ (Princeton)

014年 10月 18日 12:03

書評:福山的《政治秩序與政治衰敗》

DAVID POLANSKY

《政治秩序的起源》談論了直到拿破侖1806年在耶拿凱旋的全部人類歷史,而《政治秩序與政治衰敗》這本新書的內容則更加適度地局限在了自那之后直至現在這個時間段內。這個時間上的劃分標志著一套特定政治制度——現代國家、法治和負責制政府——發展(速度越來越快)成為全球社會政治組織主要模型這一時期的開始。福山意簡言賅地把這一全球歷史進程總結為“到達丹麥”(getting to Denmark)。

《政治秩序與政治衰敗》分四個主題部分:西歐和北美現代國家的建立;其向世界其他地區不同程度的擴張;在此過程中民主的同步傳播(和興衰);此前成功的民主政府制度——尤其是在美國——的衰敗(即書名中的“政治衰敗”)。

值得稱道的是,福山基本上沒有宣揚一種能解釋一切的宏大理念。不過如果說他有一個最主要的論述,那就是:人類具有某些偏愛自己親友(相當於其他人而言)的生物本能。福山將此稱之為世襲主義。成功的政治秩序應包括某些政治制度的建立,這些制度需能克服這些本能,並引導這些本能發揮建設性作用,產生對公眾有益的結果。自工業革命及市場資本主義(即全球化)的傳播以來,最成功地實現這一壯舉的制度是具備法治和一定程度民主問責制的現代國家。而我們所稱之為腐敗的現象,則是此類制度的不完美實現(抑或缺失)。該書最後部份專門探討的政治衰敗是指這樣一種狀況:隨著時間推移而僵化的公共制度越來越難以控制世襲本能自然的重新抬頭。

值得稱道的是,福山基本上沒有宣揚一種能解釋一切的宏大理念。不過如果說他有一個最主要的論述,那就是:人類具有某些偏愛自己親友(相當於其他人而言)的生物本能。福山將此稱之為世襲主義。成功的政治秩序應包括某些政治制度的建立,這些制度需能克服這些本能,並引導這些本能發揮建設性作用,產生對公眾有益的結果。自工業革命及市場資本主義(即全球化)的傳播以來,最成功地實現這一壯舉的制度是具備法治和一定程度民主問責制的現代國家。而我們所稱之為腐敗的現象,則是此類制度的不完美實現(抑或缺失)。該書最後部份專門探討的政治衰敗是指這樣一種狀況:隨著時間推移而僵化的公共制度越來越難以控制世襲本能自然的重新抬頭。

福山沒有將這些結果歸咎于任何單個原因,他更願意對導致秩序及腐敗的各種相互影響的發展過程進行追蹤。因此,這部作品有很大一部分內容是對一系列令人眼花繚亂的主題的二次文獻進行匯總和複述。他在介紹和快速概述一系列問題時的流暢思路無不令讀者感到欽服,例如國家的社會建構、困擾現代地中海國家政府的合法性問題、孟德斯鳩(Montesquieu)對地理與制度關係的闡釋等等。

在最後一章中,福山的目的是為了呼應第一章標題所包含的承諾,第一章的標題為“政治的必要性”。福山認為,政治秩序可為我們帶來安全和財富等有價值的東西,要維持政治秩序需要持續的管理。政治秩序之所以是必需的還因為,人們與生俱來具有一種回歸競爭對手關係的本能,這既是導致政治衰敗的原因,同時也是政治衰敗的結果。他說,世襲主義的問題在任何政治制度下從來都沒有得到最終解決。

因此福山提出,政治秩序是一種持續的、人為解決自然問題的辦法。令人驚訝的是,福山在作結論時對亞里士多德“人是政治的動物”的名言予以讚同。亞里士多德和福山的觀點有的不謀而合,例如人類生物學方面的傾向是最強烈的;實際政治必須要考慮到這一點。

但亞里士多德還指出,政治的目的不是僅僅為了讓大家生活在一起,而是為了有機會讓大家生活得好。對亞里士多德而言,人們探究何謂過得好的能力便是人類動物屬性的突出體現,也正是這種能力才決定了政治的必要性。福山在此處暗示,政治扮演著一個更具有限定作用的角色,即,簡單地將天性愛互相爭辯的人們聚在一起。

儘管福山自己本身就是一個政策制定者、顧問,但他在這本書中有意地避談政策建議。相反地,他嘗試著解釋清楚政治秩序的某些基本問題。他的解釋所依據的根基是一個有關人類天性的著名的廣義綜合定義,該定義綜合了社會生物學、社會學和政治哲學等多個學科。現在的棘手之處在於,這些學科未必一定有交叉點。它們在提到人類天性對於政治生活的影響時各自有著不同的闡釋,而這對於“政治命令的哪方面最需要人們迫切關注”的問題而言具有很重要的意義。如果人類的天性是“先於政治”的,那麼,強大的國家機器就旨在限制住人們的天性,或許我們的政治參與度也會受到限制。另一方面,如果政治傾向是人類與生俱來的本性,那麼問題或許就更多體現在公民的政治參與質量上,而非政治參與度。

因此,這本有關政治秩序的書可能會引起讀者思考這樣一個問題:政治本身是人類社會面臨的一個麻煩,還是解決人類社會諸多問題的一劑良藥?

(本文作者David Polansky是多倫多大學研究政治學的一名博士生。)

如

果不是“時間簡史”(A Brief History of Time)這個詞已經被人用作書籍標題的話,它或許可以用來描述法蘭西斯•福山(Francis Fukuyama)最新作品《政治秩序與政治衰敗》(Political Order and Political Decay)及其前篇《政治秩序的起源》(The Origins of Political Order)。這兩本書橫跨了很漫長的有記錄歷史(以及有記錄之前的歷史),挖掘了一些有關“社會組織起來的基礎規則”的教訓,福山希望以此為其導師塞繆爾•亨廷頓(Samuel Huntington)在1968年出版的政治社會學經典著作《變化社會中的政治秩序》(Political Order in Changing Societies)提供補充。《政治秩序的起源》談論了直到拿破侖1806年在耶拿凱旋的全部人類歷史,而《政治秩序與政治衰敗》這本新書的內容則更加適度地局限在了自那之后直至現在這個時間段內。這個時間上的劃分標志著一套特定政治制度——現代國家、法治和負責制政府——發展(速度越來越快)成為全球社會政治組織主要模型這一時期的開始。福山意簡言賅地把這一全球歷史進程總結為“到達丹麥”(getting to Denmark)。

《政治秩序與政治衰敗》分四個主題部分:西歐和北美現代國家的建立;其向世界其他地區不同程度的擴張;在此過程中民主的同步傳播(和興衰);此前成功的民主政府制度——尤其是在美國——的衰敗(即書名中的“政治衰敗”)。

福山沒有將這些結果歸咎于任何單個原因,他更願意對導致秩序及腐敗的各種相互影響的發展過程進行追蹤。因此,這部作品有很大一部分內容是對一系列令人眼花繚亂的主題的二次文獻進行匯總和複述。他在介紹和快速概述一系列問題時的流暢思路無不令讀者感到欽服,例如國家的社會建構、困擾現代地中海國家政府的合法性問題、孟德斯鳩(Montesquieu)對地理與制度關係的闡釋等等。

在最後一章中,福山的目的是為了呼應第一章標題所包含的承諾,第一章的標題為“政治的必要性”。福山認為,政治秩序可為我們帶來安全和財富等有價值的東西,要維持政治秩序需要持續的管理。政治秩序之所以是必需的還因為,人們與生俱來具有一種回歸競爭對手關係的本能,這既是導致政治衰敗的原因,同時也是政治衰敗的結果。他說,世襲主義的問題在任何政治制度下從來都沒有得到最終解決。

因此福山提出,政治秩序是一種持續的、人為解決自然問題的辦法。令人驚訝的是,福山在作結論時對亞里士多德“人是政治的動物”的名言予以讚同。亞里士多德和福山的觀點有的不謀而合,例如人類生物學方面的傾向是最強烈的;實際政治必須要考慮到這一點。

但亞里士多德還指出,政治的目的不是僅僅為了讓大家生活在一起,而是為了有機會讓大家生活得好。對亞里士多德而言,人們探究何謂過得好的能力便是人類動物屬性的突出體現,也正是這種能力才決定了政治的必要性。福山在此處暗示,政治扮演著一個更具有限定作用的角色,即,簡單地將天性愛互相爭辯的人們聚在一起。

儘管福山自己本身就是一個政策制定者、顧問,但他在這本書中有意地避談政策建議。相反地,他嘗試著解釋清楚政治秩序的某些基本問題。他的解釋所依據的根基是一個有關人類天性的著名的廣義綜合定義,該定義綜合了社會生物學、社會學和政治哲學等多個學科。現在的棘手之處在於,這些學科未必一定有交叉點。它們在提到人類天性對於政治生活的影響時各自有著不同的闡釋,而這對於“政治命令的哪方面最需要人們迫切關注”的問題而言具有很重要的意義。如果人類的天性是“先於政治”的,那麼,強大的國家機器就旨在限制住人們的天性,或許我們的政治參與度也會受到限制。另一方面,如果政治傾向是人類與生俱來的本性,那麼問題或許就更多體現在公民的政治參與質量上,而非政治參與度。

因此,這本有關政治秩序的書可能會引起讀者思考這樣一個問題:政治本身是人類社會面臨的一個麻煩,還是解決人類社會諸多問題的一劑良藥?

(本文作者David Polansky是多倫多大學研究政治學的一名博士生。)

新聞報導

福山教授:“我依然沒錯”

以《歷史的終結》一書聞名遐邇的美國斯坦福大學教授福山在接受德國之聲採訪時強調,歷史發展證明,他25年前關於西方自由民主制標誌著人類歷史發展最高點(終點)的論斷依然正確。

(德國之聲中文網)在四分之一世紀前出版的《歷史的終結與最後一人》(The End of History and the Last Man)一著中,福山(Francis Fukuyama)教授論證說,西方自由民主制的成功標誌著社會文明演進的終點。日前在接受德國之聲駐華盛頓記者採訪時,這位斯坦福大學政治學家指出,地緣政治雖是一種穩定現象,但從長遠角度看,他依然認為,只有一種關於全球公民的重要組織理念真正具備全球意義。這一理念便是自由民主制。

問:福山教授,您1989年出版了著名的《歷史的終結與最後一人》一書。25年前,曾有不少批評者說,“ 這傢伙是錯了” 。您是否覺得,自己被誤解了,或者,您現在願意承認說,“好吧,我當時是錯了” ?

答:我想,最大的問題是遭誤解。關於歷史終結的設想是提出一個問題:歷史進程的方向為何?是朝向共產主義嗎?曾有很多知識分子認為它是方向。或者,是朝向自由民主制?從這一視角出發,我認為,我依舊是對的。

歷史,就哲學的意義而言,的確是一種發展,或曰進化,或曰現代化,即制度(institutions,亦有“結構”、“機制”、“機構”之意—編譯者註)的現代化。問題是:全球最發達的社會採用的是何種(制度)?我想,相當清楚,任何一個願意現代化的社會依然都需要有在市場經濟條件下的多種民主政治機構的結合。我不認為,中國,或俄羅斯,或者其它競爭者能真正對這一觀點構成挑戰。

您說的是中國和俄羅斯。我想談談烏克蘭。從歷史的角度看,您覺得,我們現在是在哪兒?

嗯,我認為,俄羅斯 沒有朝向一個真正的自由民主制發展,而且,它有領土野心,就地緣政治而言,它尚未消隱。但是,終極而言,我想,俄羅斯的體係是一種非常虛弱的體系。它完全取決於很高的能源代價。即使是在俄羅斯國內,我想,它也未被完全承認為是一個合法政府。所以,我想,它不構成一個真正的競爭者。

如果您看到電視畫面上的俄羅斯總統普京,或者看到他的言行舉止,您會覺得,他是您關於認可是歷史的重要導引者這一論點的典型例證嗎?

從許多方面來看,我想,是這樣的。因為,我想,他以及許多其他俄羅斯人,依舊深受舊有偏見之累,以為俄羅斯沒有得到承認,被看成是一個虛弱的國家,它的權益沒有得到西方國家的尊重,受到北約的圍堵。這樣的想法一直延續到90年代和2000年代。所以,我的確認為,對他而言,認可具有中心的意義。

西方政治家們,不管是美國的抑或歐洲的,是否應給予他承認或認可?

嗯,我覺得,已經為時過晚。很多相關問題源於1990年代的那些決定,而你當然現在無法完全無視它們。我的確認為,應該將俄羅斯視為一個有自己利益的值得嚴肅對待的國家。它可以不類同我們中間的一員,但的確應該以尊重為起點去看待它。

烏克蘭的事件類似於第二次世界大戰爆發時的現象。不過,眼下雙方都有一些妥協跡象。您覺得,冷戰是否重又出現了?

冷戰是一個非常複雜的現象。當年的冷戰是涉及全球的爭鬥,是涉及不同意識形態和不同政治制度的爭鬥。而現在所涉及的,正如大家所看到的,是一場有關俄羅斯恢復尊嚴的鬥爭,也並不超越前蘇聯疆域。所以,從這一角度看,它的確不同於冷戰。

如果談到有效體制和有效政府,您怎麼看您自己的國家— 美國?

我在一本即將出版的書中論述說,美國的政治體系在諸多方面呈現出衰敗現象,原因是,它受制於許多強大利益集團。我們頗為自豪的相互間的制約制度最終歸結成我所稱的那種“否決統治”中,即太多的團體可以否決決定。作為其結果,國會陷入癱瘓。我想,這是我們的一個大問題。

你是否認為,美國的民主機構在衰敗?它對美國在整體上意味著什麼?美國是一個處於退卻狀態的超級大國?

不,我完全不這麼看。因為,美國經濟目前異常健康,或許是主要民主經濟制國家中最健康的一個。頁岩氣、矽谷—美國有著眾多的增長和創新的源泉。我想,(美國)政治制度目前運轉不靈,但在美國社會中,私人領域總是大於公共領域。

回到《歷史的終極》一書。您對未來十年或二十年有何預測?

我想,我們將迎來艱難的時代,俄羅斯和中國都將 擴張。不過,我的確認為,那隻是一個短暫的現象,從長遠觀點看,只有一種真正重要的組織理念,那就是:市場經濟條件下的民主制的理念。所以,從長遠觀點出發,我依然樂觀。

採訪記者:Gero Schliess 編譯:凝煉

責編:李魚

沒有留言:

張貼留言

注意:只有此網誌的成員可以留言。