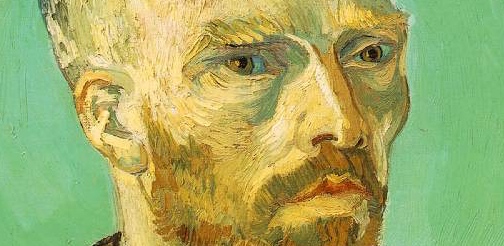

Whatever it is that accounts for the particular allure of “Self-Portrait Dedicated to Paul Gauguin,” there is no denying that it is a hard painting to forget. In photographs, the background has a tendency to come out a tranquil seafoam; in person, however, it is electric, alive. And perhaps that energy above all else is why the painting caught the eye of Maurice Wertheim, class of 1906, who bequeathed the work to Harvard upon his death in 1951. If you go to the Harvard Art Museums today, you can see it—hanging in the first room to the right of the entrance, it pulls viewers to it like moths to a light.

From a purely technical standpoint, there is no doubt that the work is extremely accomplished. But what many of the visitors drawn in by its ineffable charm may not know is that the painting has a history with richness to match: a ruined friendship, a destroyed museum, a Nazi art auction. This is that story.

STUDIO OF THE SOUTH

At the top of the painting, just below the edge of the frame, is a faint series of squiggles that viewers standing far away might be hard-pressed to recognize as letters, if they notice them at all. Heavily abraded, they are the remains of what would once have been a prominent dedication: “à mon ami Paul.”

The friend in question, of course, is none other than Paul Gauguin. Van Gogh painted the work in 1888 and gave it to his fellow artist as part of a portrait exchange that also included Émile Bernard. Later that same year, Van Gogh would succeed in convincing Gauguin to join him in Arles. “Part of the idea was to go to the south. There was a different light, a very different climate,” explains Henri Zerner, a professor of modern art in the History of Art and Architecture Department. “And the exchange of portraits is part of Van Gogh’s idea of forming a sort of art colony, an art commune, basically.”

"Someday you will also see my self-portrait, which I am sending to Gauguin, because he will keep it, I hope," Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother, Theo, in October of 1888.

Van Gogh wrote about the portrait several times in letters to his brother, Theo. One such letter, written in October of 1888, reads: “Someday you will also see my self-portrait, which I am sending to Gauguin, because he will keep it, I hope.” Before the year was out, however, their relationship imploded spectacularly. “Van Gogh was extremely emotional, obviously, and probably expected too much,” Zerner says. “And Gauguin…” Zerner shows me a letter written to him by John Rewald, a major scholar of impressionism and post-impressionism, in which the historian describes his growing disillusionment with the artist he had once so admired: “Gauguin was one of the heroes, if not the hero, of my childhood…. During my first visit to France at the age of 19, I passed all my days at the Louvre copying one of his paintings. But [Gauguin’s] writings, which I have collected for over 20 years, revealed to me little by little a fellow of often unsavory character.”

Likely as a result of their extreme personalities, the relationship between Van Gogh and Gauguin deteriorated quickly. Several months after the self-portrait’s completion, Van Gogh was committed to a mental institution following the acute psychotic episode during which he sliced off a part of his own ear. After Van Gogh’s hospitalization, they never met again. “[Their friendship lasted] a matter of months, really,” Zerner says. “Van Gogh only lives for a year and a half after [their parting]. They didn’t have a chance to make it up.”

So who tried to remove the dedication on Van Gogh’s self-portrait? The question was the subject of a 1984 investigation published by the Harvard University Art Museums’ Center for Conservation and Technical Studies (now the Harvard Art Museums and the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, respectively). H. Travers Newton, one of the two authors of the study, could not be reached for comment; Vojtech Jirat-Wasiutynski, his co-author, is deceased. Representatives of the Harvard Art Museums declined multiple requests for comment on the study.

The investigation report lays out several possible theories regarding how the dedication came to be destroyed. Though Bernard, the third member of the painting exchange, would eventually fall out with Gauguin and may thus have had motive, the study argues that it is unlikely he would have had access to the portrait. Van Gogh himself is another candidate; the authors of the investigation cite worsening mental health and increasing bitterness towards the man for whom he painted it as possible reasons. Yet according to Jirat-Wasiutynski and Newton’s report, the most likely perpetrator is none other than Gauguin. In 1897, eager to raise funds for a trip to Tahiti, Gauguin hocked Van Gogh’s self-portrait to a Parisian art dealer. It’s possible, Jirat-Wasiutynski and Newton argue, that Gauguin effaced the dedication while preparing it for sale. Even so, it sold for only 300 francs. “A workman made maybe two francs a day, so it’s probably half a year’s salary for a capable workman,” Zerner says. “But by then, Monet would sell for considerably more than that…. I would think 10 times that.”

ON THE AUCTION BLOCK

After Gauguin sold the painting, Van Gogh’s self-portrait made its way to Berlin, where, according to the Harvard Art Museums’ records, it was purchased by Hugo von Tschudi in 1906. Von Tschudi had wanted to acquire the piece for the National Gallery in Berlin, where he worked. But things didn’t go as planned. “It took a long time before it ended up in a museum,” says Sarah Kianovsky, a curator of modern and contemporary art at the Harvard Art Museums. “At that time, you needed to get approval to acquire pieces, and he couldn’t because it was too avant-garde.”

It was only upon his death in 1919 that the painting finally found its way into a museum: Von Tschudi’s wife donated the work to the Neue Staatsgalerie in Munich, where the couple had relocated. But just 20 years later the portrait was moved again, this time by the Nazis.

"It was really about putting forward one version of a culture and eliminating everything that resisted it. There were works that were put into degenerate art shows, some into markets, and some were deliberately destroyed in bonfires," says Sarah Kianovsky, a curator of modern and contemporary art at the Harvard Art Museums.

Along with the works of many artists who strayed from strict naturalistic representation, Van Gogh’s paintings were branded by the German government as “degenerate art” and suppressed by the fascists, Kianovsky explains. “It was really about putting forward one version of a culture and eliminating everything that resisted it. There were works that were put into degenerate art shows, some into markets, and some were deliberately destroyed in bonfires.” The Nazis’ targeting of “degenerate art” brought tumult to the art world: Works were removed from public museums, stolen from victims of the Holocaust, and looted from foreign art institutions as the Wehrmacht pushed outwards, she notes.

“Self-Portrait Dedicated to Paul Gauguin” did not escape the Nazis’ notice. Though records differ about the exact year of its seizure—varying documents in the Harvard Art Museums’ object file cite 1937 and 1938—by 1939 the painting had been transported to Lucerne to be sold at a Nazi-run auction.

As a fundraising endeavor, the auction was not a rousing success; many paintings were not sold, and a number that did went for as little as £20 or £30, according to the sale catalog (roughly $1,500-$1,600 in modern dollars). The Van Gogh sold for £12,000—enough of a surprise for the auctioneer to annotate the catalog with an exclamation mark. If this figure seems high compared to the other lots at auction, a comparable self-portrait by Van Gogh was purchased in 1998 for $103.8 million, making it the most expensive self-portrait ever sold.

The circumstances surrounding the auction were controversial even at the time; some collectors refused to attend. But, according to documents in the Harvard Art Museums’ object file for the self-portrait, this was not a concern shared by Wertheim, whose proxy, Alfred Frankfurter, purchased the Van Gogh. “Wertheim seemed to believe that to support what the Nazis detested was justifiable,” the file says.

Wertheim was not alone in believing his participation in the auction of Nazi-confiscated art to be justified; another buyer at the show was Joseph Pulitzer Jr., grandson of the famous journalist after whom the Pulitzer Prize is named. Pierre Matisse, the youngest son of the famous Fauvist Henri Matisse, acted as Pulitzer’s proxy and bought back his father’s “Bathers with a Turtle.” The presence of Pierre Matisse was a powerful symbol of defiance against the Nazis’ attempts to suppress “degenerate art.”

Recent years have seen increasing efforts to track down and return works that were stolen by the Nazis. “In the late ’90s, [a] government conference was convened in Washington, D.C., and this conference was about how to deal with Nazi looted art. And the result of this was the Washington Declaration,” Jutta von Falkenhausen, a German lawyer who specializes in restitution, told The Crimson for a February 2014 article on the Allies’ efforts to retrieve art stolen by the Nazis. “[The signatories] undertook whatever [was] in their power to search for looted art and find a just, fair solution—which often means restitution.” Kianovsky herself was part of an effort to investigate and clarify the provenance of several pieces in the Harvard Art Museums that had unclear origins, including works donated by Wertheim and Pulitzer.

But while much art that traded hands during this period has been the subject of restitution claims, “Self-Portrait Dedicated to Paul Gauguin” has not. “State paintings are not subject to restitution claims,” Kianovsky says. Though works that were taken from private owners or looted from foreign museums must be returned, she explains, the Van Gogh was removed by the government from a government-owned institution. Therefore, the subsequent sale was legal. Matisse’s “Bathers with a Turtle,” which originated from the Folkwang Museum in Essen, is in a similar situation.

"Leaving the collections in the state after 1945 means furthermore to demonstrate the historical situation after the Nazi regime," says Tina Nehler, a spokesperson from the Neue Pinakothek, Munich.

What’s more, the museum in which the self-portrait once hung no longer exists—the building that housed the Neue Staatsgalerie is now the Staatliche Antikensammlungen, a museum of antiquities. Kianovsky says that the Bavarian State Paintings Collections, under the purview of which the Van Gogh would have fallen while in Munich, has never asked for the paintings back, a fact that representatives from the Collections confirm. According to Tine Nehler, who works at the Neue Pinakothek, another Munich-based museum where much of the Neue Staatsgalerie’s previous collection is now housed, this is very much a deliberate choice. “Almost every European museum has paintings from other collections [that] might [have] belong[ed] to other museums before World War II,” she wrote in an emailed statement. Reverting to pre-war conditions, she said, would be a gargantuan undertaking. “Leaving the collections in the state after 1945 means furthermore to demonstrate the historical situation after the Nazi regime.” Van Gogh’s self-portrait did make its way back to Munich once since it was removed, participating in a temporary exhibition at the Neue Pinakothek in 1997.

In yet another twist, the painting’s seizure may be precisely the reason why it still exists today. As the war intensified, the Neue Staatsgalerie was forced to shut its doors. For safety, a large portion of the museum’s collection was transported either to store houses outside the city or to other museums, but a number of works were stored in the building’s cellar. An Allied bombing raid severely damaged the structure; many works inside were destroyed.

"It is a great picture. It might even be [Van Gogh's] most famous self-portrait, so we are very lucky to have it here," says Henri Zerner, a professor of modern art in the History of Art and Architecture Department.

REFLECTING ON THE SELF

Seventy-six years since the auction in Lucerne, Van Gogh’s “Self-Portrait Dedicated to Paul Gauguin” is now one of the most iconic works of the Harvard Art Museums’ collections. With its luminous green background, it has a tendency to arrest the gaze of even the most casual visitor, demanding more prolonged attention. It is a fate that in all likelihood Van Gogh never imagined for what he had intended to be a gift for a friend.

Scarcely two years after he completed the work, Van Gogh was again seized by the depression that had destroyed his dreams of founding a long-term artistic commune with Gauguin. Wading out into a field of wheat, Van Gogh shot himself through the chest. Though the wound itself was not enough to kill, the attendant infection proved fatal. He died in his brother’s arms.

“It is a great picture,” Zerner says. “It might even be [Van Gogh’s] most famous self-portrait, so we are very lucky to have it here.” From an artist’s collective in Arles to Gauguin’s Paris studio, from an art dealer in Berlin to a state museum in Munich, from an auction of “degenerate art” to pride of place on the walls of the Harvard Art Museums: This painting, there is no doubt, has had quite a journey.

—Staff writer Erica X Eisen can be reached at erica.eisen@thecrimson.com.

沒有留言:

張貼留言

注意:只有此網誌的成員可以留言。