【五無閒話.列寧廚房】波蘭作家維特多.沙博爾夫斯基(Witold Szabłowski)新作《克里姆林宮的餐桌》以食物為線索,穿連起俄羅斯政權的歷史圖像。丘庭傑聚焦書內〈列寧的廚師〉一章,認為儉樸的列寧隱瞞擁有廚師一事,恰精準暴露了列寧主義變質的病根所在。

//列寧不好甜食,原因是當時的人認為甜食缺乏男子氣概。其實不止甜食,他根本就不好於食。人家給什麼,他就吃什麼,對於美食沒有任何追求。列寧的成長可以在麵包裏看出端倪,他是吃白麵包長大的。在當時,一般鄉村人家、農民階級都是吃黑麵包(裸麥麵包)的,而精英階級吃的是白麵包。在俄國美食史家威廉 ‧ 波赫列布金的筆下,這彷彿是具象徵意義的:黑麵包比白麵包其實更有營養,富裕人家雖然吃白麵包,但會從其他來源攝取營養。而列寧父親雖然是地區教育處處長,但財力比富豪還是有很大差距,於是列寧從小就沒有吸收到充分的營養,長大後也沒有補充,晚年才會生重病早逝。在我看來,這無疑誇大了麵包的營養效益,比較重要倒是提示了列寧的家庭背景,一個能吃上白麵包但與真正富豪有本質差異的人生,或許對列寧的革命人生有一定啟示。

在導賞員的描述中,列寧最愛吃的是炒蛋(列寧說的「炒蛋」其實不攪開蛋白、蛋黃,即是煎太陽蛋)配牛奶。列寧自己不下廚,他的伴侶克魯普斯卡婭則只會做 3 道菜:煎蛋、煎雙蛋、煎三蛋。因此,列寧在海外活動大概吃了許多雞蛋。至於牛奶,列寧自小在家養成了喝生乳的習慣。生乳好像很高級,現在日式超市的生乳賣得比一般牛奶貴上幾倍,因為那是純牛奶,經過嚴格殺菌消毒。列寧喝的可能不是同一回事。當時的鄉下地方可以從乳牛身上直接擠出牛奶來喝,在運送到城裏的路上,可能受各種細菌污染。列寧個子瘦弱,長期受胃病所困,與此有關也不為奇。

茨威格在《人類群星閃耀時》的〈封閉的火車〉同樣寫列寧。他選擇的時刻,是列寧聽聞沙皇尼古拉二世退位的消息,1917 年 4 月 9日決心在瑞士踏上火車,前往那片闊別 14 年的俄羅斯大地,「這一刻起,世界的時鐘改變了運行」。這可能是列寧人生中的最重要一刻,不止是後來的十月革命、大饑荒,它掀起的紅色革命風潮延續至今。維特多的《克里姆林宮的餐桌》選擇了另一時刻。列寧擁有廚師一直是機密,維特多以此事總結這章:「撇開列寧的種種惡行不談,他已經是整個俄羅斯及蘇聯時期的統治者中,最貼近人民,也最關心人民的一位。所以,也許從他擁有私人廚娘的那一刻起,原是為人民而進行的革命,便開始與人民漸行漸遠,接只能說每况愈下。」看到這裏,我很佩服維特多的文字功力。他準確地捕捉了列寧變質的一刻,也點出了列寧主義的病根所在。//

Who did two or three million men in

That’s a lot to have done in,

But where he did one in

That grand Marxist Stalin did ten in

http://econ.st/1IOcyys

do someone in

Works[edit]

Historical and political[edit]

Common Sense About Russia (1960)

Power and Policy in the USSR (1961)[27]

The Soviet Deportation of Nationalities (1960)[27]

Courage of Genius: The Pasternak Affair (1961)[27]

Russia After Khruschev (1965)[27]

The Great Terror: Stalin's Purge of the Thirties (1968)

The Great Terror: A Reassessment (1990)[27]

The Great Terror: 40th Anniversary Edition (2008)[27]

Where Marx Went Wrong (1970)[27]

Lenin (1972)[27]

Kolyma: The Arctic Death Camps (1978)[27]

Present Danger: Towards a Foreign Policy (1979)[27]

We and They: Civic and Despotic Cultures (1980)[27]

Inside Stalin's Secret Police: NKVD Politics, 1936–1939 (1985)[27]

What to Do When the Russians Come: A Survivor's Guide (with Jon Manchip White, 1984)[27]

The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine (1986)[27]

Tyrants and Typewriters: Communiques in the Struggle for Truth (1989)[27]

Stalin and the Kirov Murder (1989)[27]

Stalin: Breaker of Nations (1991)[27]

History, Humanity, and Truth (1993)[27]

Reflections on a Ravaged Century (1999)[27]

The Dragons of Expectation: Reality and Delusion in the Course of History, W. W. Norton & Company (2004), ISBN 0-393-05933-2

Poetry[edit]

Poems (1956)[27]

Between Mars and Venus (1962)[27]

Arias from a Love Opera, and Other Poems (1969)[27]

Forays (1979)[27]

New and Collected Poems (1988)[27]

Demons Don't (1999)[27]

Penultimata (2009)[27]

A Garden of Erses [limericks, as Jeff Chaucer] (2010)[27]

Blokelore and Blokesongs (2012)[27]

Novels[edit]

A World of Difference (1955)[1]

The Egyptologists (with Kingsley Amis, 1965)[1]

Criticism[edit]

The Abomination of Moab (1979)[1]

康奎斯特:揭露斯大林恐怖第一人

8月3日,英國著名歷史學家羅伯特·康奎斯特 (Robert Conquest)去世,享年98歲。很多人認為他是第一個揭露斯大林政權恐怖程度的人,他的著作對西方共產黨人震動極大。BBC駐首爾記者斯蒂芬·埃文斯從他的家庭經歷談起……

如果你生長在一個西方共產黨人家庭,那麼康奎斯特的著作實在震憾。

我的祖父輩有兩人是共產黨員。 我祖父在俄國十月革命後不久加入英共,對黨忠心不二,即時發生了匈牙利事變和捷克布拉格之春也沒動搖。

我祖父家在威爾士南部,一家人經常就政治話題爭論不休,但無濟於事,就像和最虔誠的教徒理論一樣。 蘇聯周刊或者英國早星報說什麼,都被看成真理。

祖父的書架上擺著斯大林著作。當祖母斗膽在飯桌上說蘇聯肯定也有犯罪時, 我祖父便告訴她,別再傳播謊言了。

這種宗教氣氛到了冷戰時期還是一樣。任何質疑蘇聯成果的討論都被說成是「冷戰宣傳」。

當一個知名的蘇聯異議人士被囚禁在精神病醫院裏時,祖父認為,這個人一定是有精神病,不然他為什麼會懷疑蘇聯社會主義制度的優越性。

對於我們當中真的抱有懷疑的人來說,羅伯特·康奎斯特的著作起到很大作用。 這書名為「巨大恐怖:斯大林三十年代的清洗運動」,發表於1968年,也就是蘇聯入侵捷克對付布拉格之春的那一年。

這本書使我們改變了看法, 驅逐了疑團。

作者讓事實說話,不加渲染,用清晰的語言講述那些鎮壓和處決的細節。一些蘇聯的吹捧者對此書嗤之以鼻,但是康奎斯特擺出的事實無懈可擊,因為他的研究非常扎實。

在前蘇聯的檔案最終解密之後,康奎斯特的描述仍然站得住腳。也許人們可以質疑被清洗的凖確人數,但是康奎斯特書中的大部分事實無可非議。

書中講到,僅在1937年到1938 年幾個月中,就有數十萬的人被蘇聯秘密警察槍決。 我們還了解到,過分猜疑的斯大林在軍隊大幅度清洗軍官,甚至影響到了紅軍的戰鬥能力。

康奎斯特描述了1937年12月12日這天,斯大林和他的劊子手莫洛托夫(Molotov)親自批准了3167人的死刑,然後兩人到電影院去看電影。

這些細節無可辯駁。

康奎斯特的另外一本書,「憂傷收成:蘇聯集體化和飢荒恐怖」,講述了1932 到1933 年烏克蘭經歷的飢荒,而飢荒正是由於斯大林殘酷推行的愚蠢和懲罰性的農業政策所導致。

在村莊裏,由於飢餓,出現吃人現象。這些都記錄在康奎斯特筆下。

二戰之前,著名的威爾士記者加雷斯·瓊斯(Gareth Jones)曾到烏克蘭實地見證了大飢荒,並在1933 年發表了有關文章。但是一些大腕人物站出來和瓊斯唱反調,比如紐約時報駐莫斯科記者瓦爾特·杜蘭蒂(Walter Duranty)。 他對斯大林的宣傳鸚鵡傳舌。

杜蘭蒂在當年8月的文章裏說,雖然條件很艱苦,但是烏克蘭沒有鬧飢荒。在談到斯大林政策時,他說,「不打碎雞蛋,就無法做蛋餅。」

康奎斯特的書一出版,瓊斯和杜蘭蒂到底誰對誰錯,便不爭自明。

不要忘了在冷戰時期,雖然一些共產黨感到失望,抱怨上帝已去,但是對堅定的共產黨員來說,既是事實擺在他們面前。他們的信念也不會動搖。

1956年赫魯曉夫開始清算斯大林時,我祖父患了病,斯大林的著作也被挪到了電視後邊。

他在蘇聯解體時去世。那時他年老體衰,無法意識到他的上帝已去。他從來沒有讀過康奎斯特的書 – 即使讀了, 他也會認為那是令人作嘔的冷戰宣傳。

據說墨西哥作家奧克塔維奧·帕斯(Octavio Paz)對康奎斯特著作的評價是,它們給斯大林主義「蓋棺論定」, 結束了那場辯論。事實並非如此。現在仍然有人懷念斯大林, 就是俄國大概也不例外。

但是康奎斯特的書的確使那些希望尋求真相的人大開眼界。

我知道那種滋味。 我記得。

(編譯:華英/責編:晧宇)

George Robert Acworth Conquest, CMG, OBE, FBA, FAAAS, FRSL, FBIS (15 July 1917 – 3 August 2015) was a British-American historian and poet, notable for his influential works on Soviet history including The Great Terror: Stalin's Purges of the 1930s (1968). He was a research fellow at Stanford University's Hoover Institution.

Contents [hide]

1 Early career

2 The Great Terror

3 Later works

4 Poetry

5 Later life

6 Awards and honours

7 Works

7.1 Historical and political

7.2 Poetry

7.3 Novels

7.4 Criticism

8 See also

9 References

10 External links

Robert Conquest: scholars pay tribute to pioneering historian

Poet and Russia scholar has died at the age of 98

SOURCE: ROB C. CROES (ANEFO)

Leading academic experts on the Soviet Union have paid tribute to the poet and historian Robert Conquest, who died this week at the age of 98.

For Robert Gellately, Earl Ray Beck professor of history at Florida State University, he was “a pioneer in the study of Soviet terror, though because he was often deemed a conservative opponent of communism, everything he said could safely be ignored”.

“Many academics in particular were deaf to the abuses of communism, and many still find it difficult to question the utopian dream that so obviously turned into a nightmare,” Professor Gellately said. “Conquest was one of the few to have the courage to tackle the daunting research task, even to question his own once-cherished beliefs, and to devote a lifetime’s energy to get people to see the light.”

Stephen Kotkin, professor in history and international affairs at Princeton University, described Conquest as “a phenomenon – an accomplished poet, a scholar of surpassing erudition, and a witty, mischievous raconteur. He wrote some 30 history and policy books, one of which was among the two most important on the Soviet Union during the entire Cold War. The Great Terror: Stalin’s Purge of the Thirties (1968) was a masterpiece of connect-the-dots research and storytelling. The only other work on the same plane is Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago (1973).”

Although Professor Kotkin acknowledged that “Conquest might be faulted for having an insufficiently complex theory of power”, he was working at a time “when Soviet archives were effectively closed to legitimate researchers” and yet still managed to “demonstrate with massive detail, by recourse to memoirs, Khrushchev-era publications and Kremlinology, what the Soviet Union and Stalin’s rule really were. His impact in academia was blunted by the politics of the profession, but his impact on the public and policymakers was profound.”

Orlando Figes, professor of history at Birkbeck, University of London, noted that after the collapse of Soviet Union in 1991, Conquest was “practically a hero [in Russia] for having told the truth about the Stalin terror when everybody else was telling lies. The opening of the Soviet archives more than vindicated Conquest’s original findings (he published a second edition of The Great Terror with the sub-heading ‘a Reassessment’ [1990]), which had never been accepted by left-wing ‘revisionists’ – inclined as they were not only to underestimate the numbers killed and destroyed in the terror but to fail to understand the impact of the terror on Soviet society.”

A mildly dissenting note was struck by Sheila Fitzpatrick, honorary professor of history at the University of Sydney: “Robert Conquest was a bit too much of a Cold Warrior for my taste, but hisGreat Terror was an important contribution to the scholarship when it first came out, and then had an interesting afterlife in Russia as a much-prized ‘truth about the purges as told in the West’ in the early post-Soviet period. Of course, by that time, there were better data on the numbers than he had (Conquest was never good on numbers; my impression was that he just went for high ones), but the Russians didn’t mind about that.”

Robert Conquest was born on 15 July 1917 and died 3 August 2015.

The lives and limericks of Robert Conquest

The poet and historian died on 3 August, having published more than 20 books on Soviet history. But how many people know about his love of a silly rhyme?

Blake Morrison

Thursday 6 August 2015 17.32 BST

A week during which the last surviving Dambuster pilot died also saw the death, at 98, of another anti-totalitarian figurehead, the poet and historian Robert Conquest. Born earlier than the Movement generation of writers he helped promote with his 1956 anthology New Lines (Philip Larkin, Kingsley Amis, DJ Enright, Donald Davie and Elizabeth Jennings among them), Conquest outlived his proteges by some distance, in the case of Larkin by 30 years. He also outwrote them, in numbers of pages produced, publishing more than 20 books on Soviet history.

When the most famous of these, The Great Terror, came out in 1968, no one of liberal or leftist persuasion wanted to believe its claims about the millions killed by Stalin. An ex-communist, Conquest had already shown his colours by pledging support for the US war in Vietnam. But history has mostly vindicated his research on Stalin (Amis suggested the book be reissued under the title I Told You So, You Fucking Fools). In the US, where he lived for many years and was awarded the presidential medal of freedom, he is revered for his part in the cold war.

A sillier side of him deserves recognition here: his talent for limericks. He revelled in their succinctness: “There was a great Marxist named Lenin / Who did two or three million men in. / That’s a lot to have done in / But where he did one in / That grand Marxist Stalin did ten in.” Another effort revises Shakespeare’s seven ages of man: “First puking and mewling, / Then very pissed off with your schooling, / Then fucks and fights, / Then judging chaps’ rights, / Then sitting in slippers, then drooling.” Others are donnishly witty, albeit obscene: “When a man’s too old even to toss off, he / Can sometimes be consoled by philosophy. / One frequently shows a / Strong taste for Spinoza / When one’s balls are beginning to ossify.” Or again: “There was a young fellow called Shit, / A name he disliked quite a bit, / So he changed it to Shite, / A step in the right / Direction, one has to admit.”

Gentler in person than his robust masculinist pose would suggest, his voice reduced to a whisper in later years, Conquest attracted several younger admirers, including Christopher Hitchens and Martin Amis. But it’s in the work of Larkin and Amis Senior that his presence is most strongly felt. There’s a book to be written about his influence on them. Meanwhile someone ought to publish a definitive book of the limericks.

國際

英國著名蘇共史學家逝世(英文)

WILLIAM GRIMES 2015年8月5日

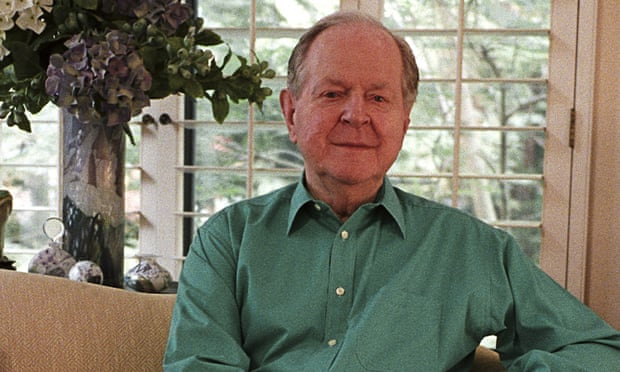

Linda A. Cicero/Stanford News Service

2010年,羅伯特·康奎斯特在家中。

摘要:英國著名歷史學家、蘇聯專家羅伯特·康奎斯特於週一因肺炎去世,享年98歲。康奎斯特在上世紀50年中期開始對蘇聯歷史進行研究,是西方史學界研究1930年代斯大林執政下的“大清洗”運動和烏克蘭大饑荒歷史的權威專家之一,著有《大恐怖》一書。

Robert Conquest, a historian whose landmark studies of the Stalinist purges and the Ukrainian famine of the 1930s documented the horrors perpetrated by the Soviet regime against its own citizens, died on Monday in Stanford, Calif. He was 98.

His wife, the former Elizabeth Neece, said the cause was pneumonia.

Mr. Conquest, a poet and science-fiction buff, turned to the study of the Soviet Union in the mid-1950s out of dissatisfaction with the quality of analysis he saw at the British Foreign Office, where he worked after World War II in the Information Research Department, a semi-secret office responsible for combating Soviet propaganda.

“The ambassadors varied between people who were interested in politics and people who were interested in music,” he told The Guardian in 2003. “I wanted to study the evolutions at the top in Soviet Russia.”

As one of the Movement poets of the 1950s, a group that included Kingsley Amis, Philip Larkin and Thom Gunn, Mr. Conquest embarked on a research fellowship at the London School of Economics and produced “Power and Politics in the USSR” (1960) , a book that established him as a leading Kremlinologist.

Eight years later, during the Prague Spring, he published “The Great Terror: Stalin's Purge of the Thirties,” a chronicle of Stalin's merciless campaign against political opponents, intellectuals, military officers — anyone who could be branded an “enemy of the people. ”

For the first time, facts and incidents scattered in myriad sources were gathered in a gripping narrative. Its impact would not be matched until the publication of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's “The Gulag Archipelago” in 1973.

The scope of Stalin's purges was laid out: seven million people arrested in the peak years, 1937 and 1938; one million executed; two million dead in the concentration camps. Mr. Conquest estimated the death toll for the Stalin era at no less than 20 million.

“His historical intuition was astonishing,” said Norman M. Naimark, a professor of Eastern European history at Stanford University. “He saw things clearly without having access to archives or internal information from the Soviet government. We had a whole industry of Soviet historians who were exposed to a lot of the same material but did not come up with the same conclusions. This was groundbreaking, pioneering work.”

Reaction to the book split along ideological lines, with leftist historians objecting to Mr. Conquest's thesis that Stalin's regime was a natural evolution of Leninism rather than an aberration.

Mr. Conquest summed up his attitude in a short poem:

There was a great Marxist called Lenin

Who did two or three million men in.

That's a lot to have done in,

But where he did one in

That grand Marxist Stalin did ten in.

“The Great Terror: A Reassessment” included new information made available after the collapse of the Soviet Union. It was less a reassessment, however, than a triumphant vindication of the original edition, since newly released material from the Soviet archives supported Mr. Conquest's findings at every turn.

“In the circumstances, Mr. Conquest is merely left to dot the i's,” the historian Norman Davies wrote in The New York Times Book Review . In a moment of gleeful malice, Mr. Conquest told friends that his suggested title for the new edition was “I Told You So, You Fools” (with a vulgar adjective inserted between the last two words).

Russian editors in the post-Soviet era, savoring a newfound freedom, published excerpts from “The Great Terror” and other Conquest works. “This is by far the most serious work on the period of our history between 1934 and 1939,” wrote Boris Nikolsky, editor of the Russian journal Neva.

Mr. Conquest returned to the subject of the 1930s in 1986 with his study “The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine,” covering Stalin's campaign to bring Ukraine to heel and pay for industrial development by expropriating grain from peasant farmers. Millions perished in the ensuing state-organized famine and wave of mass arrests. In his preface, Mr. Conquest noted that “in the actions here recorded about 20 human lives were lost, not for every word, but for every letter, in this book .”

Together, “The Great Terror” and “The Harvest of Sorrow” offered the definitive account of the crimes of the Stalin era.

George Robert Acworth Conquest was born on July 15, 1917, in Great Malvern, Worcestershire, England. His father lived on a trust-fund income, and throughout Mr. Conquest's childhood the family shifted from one home to another and spent long periods in France , in Brittany and Provence.

He attended Winchester College in England and, after studying for a year at the University of Grenoble in France and traveling through Bulgaria, enrolled at Magdalen College, Oxford, where he studied politics, economics and philosophy and joined the Communist Party.

When World War II began in 1939, he joined the Oxford and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry. After studying Bulgarian, he served as an intelligence officer in Bulgaria, where he remained after the war as the press officer at the British Embassy in Sofia.

In 1942 he married Joan Watkins, the first of his four wives. In Bulgaria he began a relationship with Tatiana Mihailova, whom he helped escape to Britain after the Soviet takeover of Bulgaria and married. She was later found to have schizophrenia, and they eventually divorced. In addition to his fourth wife, he is survived by sons from his first marriage, John and Richard; a stepdaughter, Helen Beasley; and five grandchildren.

Mr. Conquest was known as a poet before he began writing history. With Kingsley Amis, whom he met in 1952 when Mr. Amis was writing “Lucky Jim,” he edited volumes of the poetry anthology “New Lines,” which showcased work by Movement poets.

Their style — spare, vernacular, direct — broke with the florid romanticism and mysticism of Dylan Thomas. Mr. Conquest formed a fast bond with Mr. Amis after reciting “Mexican Pete,” a sequel to the bawdy song “The Ballad of Eskimo Nell ” that he wrote with John Blakeway.

Mr. Conquest's poetry collections include “Between Mars and Venus” (1962) and “Arias From a Love Opera” (1969).

Mr. Conquest and Mr. Amis shared a love of science fiction that they indulged by editing “Spectrum,” a series of five anthologies that presented quality science-fiction stories from the 1940s and '50s. Mr. Conquest tried his hand at the genre in “A World of Difference” (1955), set in far-off 2010, and collaborated with Mr. Amis on the comic novel “The Egyptologists” (1965).

Mr. Conquest published many books on the Soviet system and politics. They included “Russia After Khrushchev” (1965); “Industrial Workers in the USSR” (1967); “The Nation Killers: The Soviet Deportation of Nationalities” (1970), which was revised and reissued as “Stalin: Breaker of Nations” (1991); and “Kolyma: The Arctic Death Camps” (1978). In 1977 he became a senior research fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. He lived in Stanford .

Over time, he emerged as a forceful polemicist on Cold War politics and the ideological struggle between East and West, taking an uncompromisingly anti-Soviet line and attacking the utopian political theories embodied in what he called “ideomaniac” states. Many of his essays were collected in “Reflections on a Ravaged Century” (1999) and “The Dragons of Expectation: Reality and Delusion in the Course of History” (2005).

“I think that sometimes people say the democrats are shortsighted and muddle-headed,” Mr. Conquest once told NPR. “But I think you want to be a bit shortsighted. It's better than having a long sight into a nonexistent future.

沒有留言:

張貼留言