《包浩斯書籍8》(Bauhausbücher 8)指的是拉茲洛·莫霍利-納吉(László Moholy-Nagy)1925年出版的開創性著作《繪畫、攝影、電影》(德語:Malerei, Fotografie, Film)。該書是包浩斯系列叢書中的重要文本,探討了視覺藝術的演變以及攝影和電影等新興技術,強調了機器時代藝術的新願景。拉爾斯·穆勒(Lars Müller)的現代復刻版現已廣泛發行。

《包浩斯書籍8》的關鍵要素:

作者:匈牙利藝術家、攝影師、包浩斯教師拉茲洛·莫霍利-納吉(1895–1946)。

內容:本書論證了攝影和電影製作作為重要藝術形式的地位,挑戰了傳統繪畫,並倡導在現代科技社會中對視覺文化進行徹底的反思。

設計:這本書本身就成為了包浩斯設計的標誌性範例,其字體和版面(通常採用疊印圖像)都成為了其意義不可或缺的一部分。

系列:根據字母形式檔案館(Letterform Archive)記載,它是極具影響力的包浩斯書籍系列(Bauhausbücher)的第八卷,該系列匯集了包浩斯大師們的核心理念。

影響:莫霍利-納吉在這本書中的作品為他後來在芝加哥新包浩斯中探索的概念奠定了基礎,並影響了幾代藝術家和設計師,正如這段YouTube影片和這段YouTube影片所指出的那樣。

現代版:像Lars Müller這樣的當代出版社推出了復刻版,忠實地再現了莫霍利-納吉的原始設計和字體,以吸引新的讀者,正如這個亞馬遜頁面所示。

- Author: Hungarian artist, photographer, and Bauhaus instructor László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946).

- Content: It argues for photography and filmmaking as essential art forms, challenging traditional painting and advocating for a radical rethinking of visual culture in modern, technological society.

- Design: The book itself became an iconic example of Bauhaus design, with its typography and layout, often featuring overprinted images, becoming integral to its meaning.

- Series: It was the eighth volume in the influential Bauhausbücher series, which collected core ideas from Bauhaus masters, notes the Letterform Archive.

- Legacy: Moholy-Nagy's work in this book laid groundwork for concepts later explored in his New Bauhaus in Chicago and influenced generations of artists and designers, notes this YouTube video and this YouTube video.

- Contemporary publishers like Lars Müller offer facsimile editions that faithfully reproduce Moholy-Nagy's original design and typography for new audiences, as seen on this Amazon page.

László Moholy-Nagy

-------

-------

人工智慧概述

歷史記錄或記載中沒有任何證據表明包浩斯創始人沃爾特·格羅皮烏斯親自為學生洗腳。

「為學生洗腳」的說法似乎源於對一張歷史照片和一則關於學生生活條件的軼事的誤解:

洗腳池:一張來自「森林學校」(影響了包浩斯理念)的照片顯示,一些身著泳裝的年輕男子正在走廊的洗腳池中洗腳。這些洗腳池是學校設施的實用組成部分,很可能是為了方便學生在使用附近的運動場或露天游泳池後進行清潔,這與魏瑪共和國的「生活改革運動」理念相符。

格羅皮烏斯的權威:格羅皮烏斯以其對新型教育機構的執著以及對學校強大而穩定的組織而聞名。他被認為是一位先鋒建築師和權威人物,而不是會去做像為學生洗腳這樣卑微的僕人式工作的人。

「建築師如神」軼事:關於格羅皮烏斯在哈佛的一段軼事凸顯了他對設計的堅定信念:據說,當被問及如果學生不喜歡他精心設計的宿舍會怎樣時,格羅皮烏斯回答說:「那這個學生就是神經質。」 這表明他更傾向於貫徹自己的理念,而非以謙遜的態度服務學生。

這種說法很可能源自於對包浩斯共享、公共且功能性的生活環境的誤解,而這正是包浩斯社會和設計理念的核心所在。

- Foot Washing Basins: A photograph from the "School in the Woods" (which influenced Bauhaus ideals) shows young men in swimwear washing their feet in a basin in a corridor. These basins were a functional part of the school's facilities, likely for hygiene after using nearby sports grounds or an open-air swimming pool, aligning with the "life reform movement" precepts of the Weimar Republic.

- Gropius's Authority: Gropius was known for his dedication to a new kind of educational institution and a strong, consistent organization of the school. He was considered a pioneering architect and a figure of authority, not someone who would perform a menial, servant-like task like washing students' feet.

- The "Architect as God" Anecdote: An anecdote about Gropius at Harvard highlights his strong convictions about design: when asked what would happen if a student disliked his precisely designed accommodations, Gropius reportedly replied, "Then the student would be neurotic". This indicates a personality that enforced his vision rather than served students in a humble capacity.

------

JosefAlbers1888-1976. 1940;Like an Egyptian … psychology and the riddle of style. 「向方形致敬」的色彩大師──約瑟夫・亞伯斯(Josef Albers) 作者:賴嘉綾 /

🎉#HappyBirthday🎂to artist #JosefAlbers, born #onthisday in 1888. Photo at Black Mountain College, 1940.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Happy birthday to Josef Albers, one of the most important teachers and influential personalities at the Bauhaus from its inception. “Homage to the Square" is a collection of explorations in color and spatial relationships in which Albers limited himself to square formats, solid colors and precise geometry, yet was able to achieve a seemingly endless range of visual effects.

Josef Albers | Homage to the Square: Soft Spoken | 1969

METMUSEUM.ORG

Josef Albers

Artist

Josef Albers was a German-born American artist and educator whose work, both in Europe and in the United States, formed the basis of some of the most influential and far-reaching art education programs of the twentieth century. Wikipedia

Born: March 19, 1888, Bottrop, Germany

Died: March 25, 1976, New Haven, Connecticut, United States

Now on view at the School of Art’s 32 Edgewood Avenue Gallery, "Search Versus Re-Search: Josef Albers, Artist and Educator," an exhibition featuring works by Albers, former chair of the school’s Department of Design, alongside student works from his classroom.

Yale School of Art exhibition examines impact of Josef Albers’ art and teaching

The Yale School of Art launches its 2015–2016 season with an exhibition...

NEWS.YALE.EDU

「向方形致敬」的色彩大師──約瑟夫・亞伯斯(Josef Albers)

作者:賴嘉綾 /

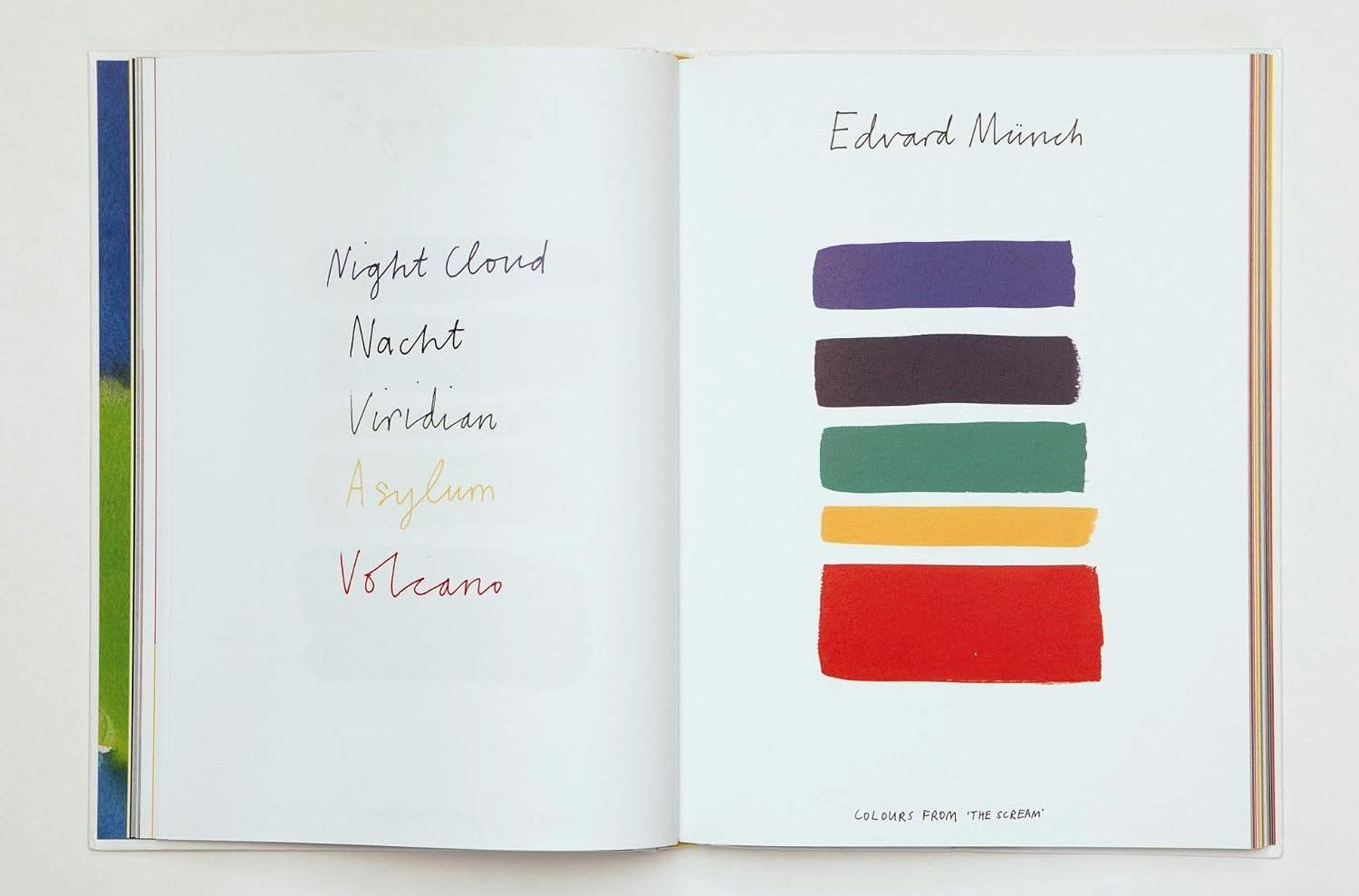

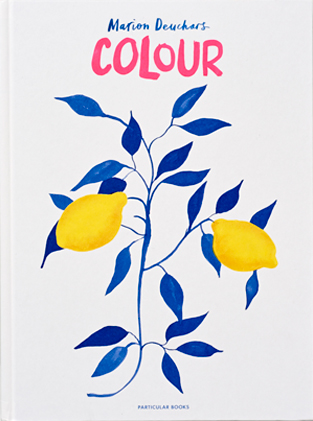

之前拜訪瑪莉安.杜莎(Marion Deuchars)時,她說每天到工作室的第一件事,通常先用顏色暖身。方法有好幾種,最常用的是從一張名畫裡挑顏色複製,在自己的調色盤上調出最接近畫上的顏色,完成紀錄;譬如高更、梵谷、歐姬芙、孟克都是她練習的對象,某些畫家的顏色很難模仿,即使只模擬五個顏色,也要分好幾次才完成,不過後來越來越得心應手。

練習模擬畫家的五個常用色。(圖 / Colour 內頁)

練習模擬畫家的五個常用色。(圖 / Colour 內頁)

另一種是使用點畫,她採用同心圓式的點法,以八個點為中心最小的一圈,然後14、20、26、32⋯⋯漸次擴大範圍。可以是同色系或是七彩變化的,畫點的時候養成的專注尤其能夠穩定心情。還有其他以潑灑、剪貼、或以「色系」來列舉顏色的名稱,尋找顏色的差異與命名。後來這些作法結集成一本書,書名是 Colour。其中有一跨頁上列出24種微差異的黑色;另外還有一頁說明顏色與其互補色放在一起有什麼樣的效果,譬如橘色與藍色是最撞色的組合之一,如果將橘色方形放在藍色方形裡,有什麼樣的效果呢?如果在兩個顏色之間加上灰色,對顏色的感覺會有改變嗎?

同心圓的顏色練習。(圖 / Colour 內頁)

同心圓的顏色練習。(圖 / Colour 內頁)

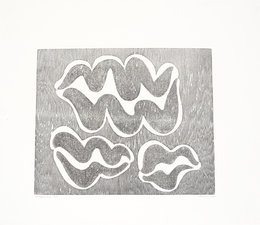

而藝術史上以「方形色塊組合」聞名的約瑟夫・亞伯斯(Josef Albers, 1888-1976),實踐了色彩的相對關係,留給世人近兩千幅名畫。他證明色彩的感受除了上面列舉的光、彩、反射、折射、視神經,也受到相鄰顏色的影響。他的正方形抽象畫上重疊著不同的色彩組合,在繁複的畫派裡獨樹一格。

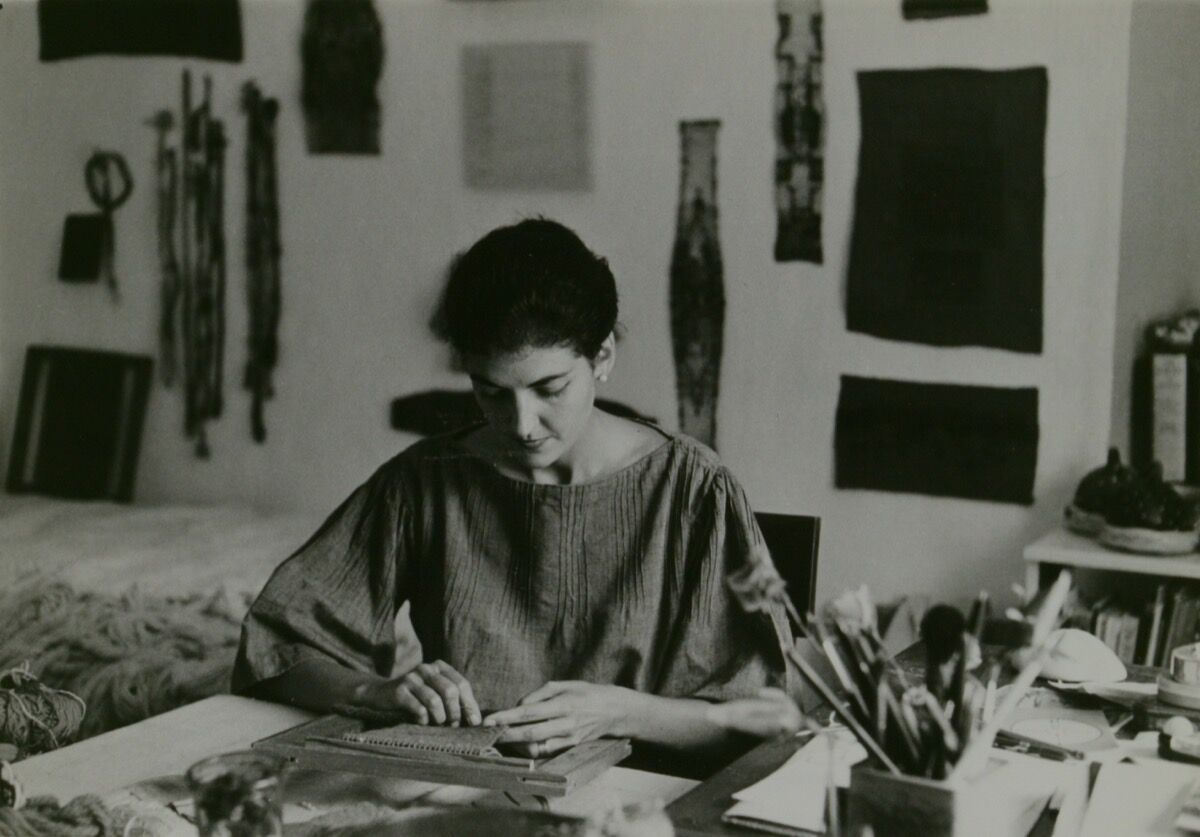

1888年出生在德國的亞伯斯,1919年進入包浩斯當學生時已經31歲,但他畢業後就被延聘為青年大師(junior master)的職位,教授媒材運用,關於玻璃、紙張、木料、金屬,他都有研究;1922年女學生安妮(Anni Fleischmann, 1899-1994)進入包浩斯就讀,是紡織藝術類的。他們在1925年結婚,留在包浩斯繼續工作。能進入包浩斯當學生的都是已經在個別領域裡的熟手,包浩斯是一個融合教學、研究、設計和接案的地方,成品與收入歸於校方所有。因為希特勒政權施壓包浩斯,1933年學校關閉。亞伯斯夫婦轉任教於美國北卡羅萊納州的「黑山學院」(Black Mountain College),這是一個僅存24年(1933-1957)的藝術學院,養成了眾多當代藝術家。

+++++

Oskar Schlemmer1888.:The letters and diaries. The theater of the Bauhaus. VISIONS OF A NEW WORLD 2014;Bauhaus Journal, okt.-dez. 1929

奧斯卡‧施萊默 (1888-1943) 維爾納‧西多夫 (1899-1976):《空間中的人物》1927

攝影:T·盧克斯·費寧格(西奧多·盧卡斯·費寧格)(1910-2011)

德國德紹包浩斯

文獻:T·盧克斯·費寧格藝術檔案作品全集

維爾納·西多夫出生於杜伊斯堡,20世紀20年代在德紹包浩斯開始了他的演藝生涯,擔任演員、舞蹈演員和啞劇演員。西多夫大約30歲時,在奧斯納布呂克獲得了他的第一份表演工作。之後,他先後在格拉、普勞恩和法蘭克福等地演出,並於1942年戰爭期間抵達法蘭克福。他的第一任妻子阿爾瑪·西德霍夫-布舍爾(Alma Siedhoff-Buscher)是他在包浩斯認識的,於 1944 年在一次空襲中喪生。

OSKAR SCHLEMMER (1888-1943) WERNER SIEDOFF (1899-1976) : "FIGURES DANS L'ESPACE" 1927Photo : T. Lux Feininger (Theodore Lukas Feininger) (1910-2011)Documents : Catalogue raisonné T. Lux Feininger-Kunst ArchiveNé à Duisbourg, Werner Siedoff débute sa carrière dans les années 1920 en tant qu'acteur, danseur et pantomime au Bauhaus de Dessau. Siedhoff avait déjà environ 30 ans lorsqu'il reçoit son premier engagement en tant qu'acteur à Osnabrück. S'ensuivent des engagements à Gera, Plauen et Francfort-sur-le-Main, où il arrive en pleine guerre (1942). Sa première femme, Alma Siedhoff-Buscher, rencontrée au Bauhaus a été tuée lors d'un raid aérien en 1944.

Wikipedia 有 Oskar Schlemmer簡傳:

Bauhaus Journal,okt.-dez.. 1929

cover page

----https://www.press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/distributed/O/bo20202296.html

Oskar Schlemmer

VISIONS OF A NEW WORLD

Distributed for Hirmer Publishers

https://www.christies.com/features/Klee-and-Kandinsky-7441-3.aspx

有英文影片

Klee and Kandinsky at the Bauhaus

With the rise to power of the National Socialists in 1933, Germany became a dangerous place for both artists to live

幾本Wassily Wassilyevich Kandinsky (1866~1944)中文書

Vassily Kandinsky, Murnau am Staffelsee

20th century[edit]

| Mars symbol (U+2642 ♂). The symbol for a male organism or man. |

| Venus symbol (U+2640 ♀). The symbol for a female organism or woman. |

Bauhaus 學生人數

年 女 男

1919 101 104

1920 59 78

1921 44 64

1922 48 71

1923 35 106

1924 45 82

1925 28 75

1926 28 73

1927 41 125

1928 46 130

1929 58 143

1930 44 122

1931 53 141

1932 25 90

1933 5 14

----

Bauhaus 女傑,德文版多本,這是英文

Bauhausmädels. A Tribute to Pioneering Women Artists

----

Mart Stam Cantilever Armchair - 1926 without (S 33) and with armrests (S 34) These chairs are the first cantilever chairs in furniture history. They were used for the first time in 1927 in the Weissenhof-Siedlung in Stuttgart. Starting in 1925, Mart Stam experimented with gas pipes that he connected with flanges and developed the principle of cantilevering chairs that no longer rest on four legs. He thus created a construction principle that became an impo⋯⋯

Marianne Brandt - The Iron Lady

Marianna Brandt - German artist, sculptor, photographer and designer. The first and only woman who was admitted to the Bauhaus metal workshop, later taught in this workshop together with Laszlo Moholi Nadi, and in 1928 she headed it. Designed by Marianne Brandt household items are considered the forerunners of modern industrial design.

From memories M. Brandt

"... At that time I didn’t really like the painting they were doing there, and I didn’t feel that I could move in that direction. I was not at all interested in monumental painting, and in the textile workshop I didn’t like the atmosphere there. It would be interesting to do wood, but it required a lot of physical strength. In general, I discussed this issue with Moholi, and we decided that metal is what you need ... ... At first, they gave me all the most uninteresting, tedious and monotonous work It’s impossible to count how many hemispheres I patiently poke and, believing that the way it should, that the beginning is always difficult. But then everything will work out, and we became friends ... At that time we could not even dream about Plexiglas and other plastics. If we had them, it is unknown what other peaks we could reach. Well, in general, it’s good - after all, it’s necessary that those who come after us have something to do! ... "

"Bauhaus-style" - Brandt's programmatic response to Naum Gabo's skeptical article "Design?" ("Gestaltung?") In which Gabo calls the Bauhaus design superficial and anti-constructivist.

"... the author does not know us at all if he believes that we are trying to create a certain style, and that, for example, a round lamp was created solely because of admiring the pure forms of the sphere and cylinder. Today, we must start from the totality functional ideas, drawn from practical experience and our projects, which we repeatedly check and calculate. Of course, one cannot do without intuition and a general sense of balance ... yes, we make mistakes - this is inevitable, but every day they become less and less. .. "

還有 9 張

Баувху/Bauwchu 在 Marianne Brandt - The Iron Lady 相簿中新增了 12 張相片。說這專頁讚

2015年7月18日

Marianna Brandt German artist, sculptor, photographer and designer. The first and only woman who was admitted to the Bauhaus metal workshop, later taught in thi⋯⋯

----

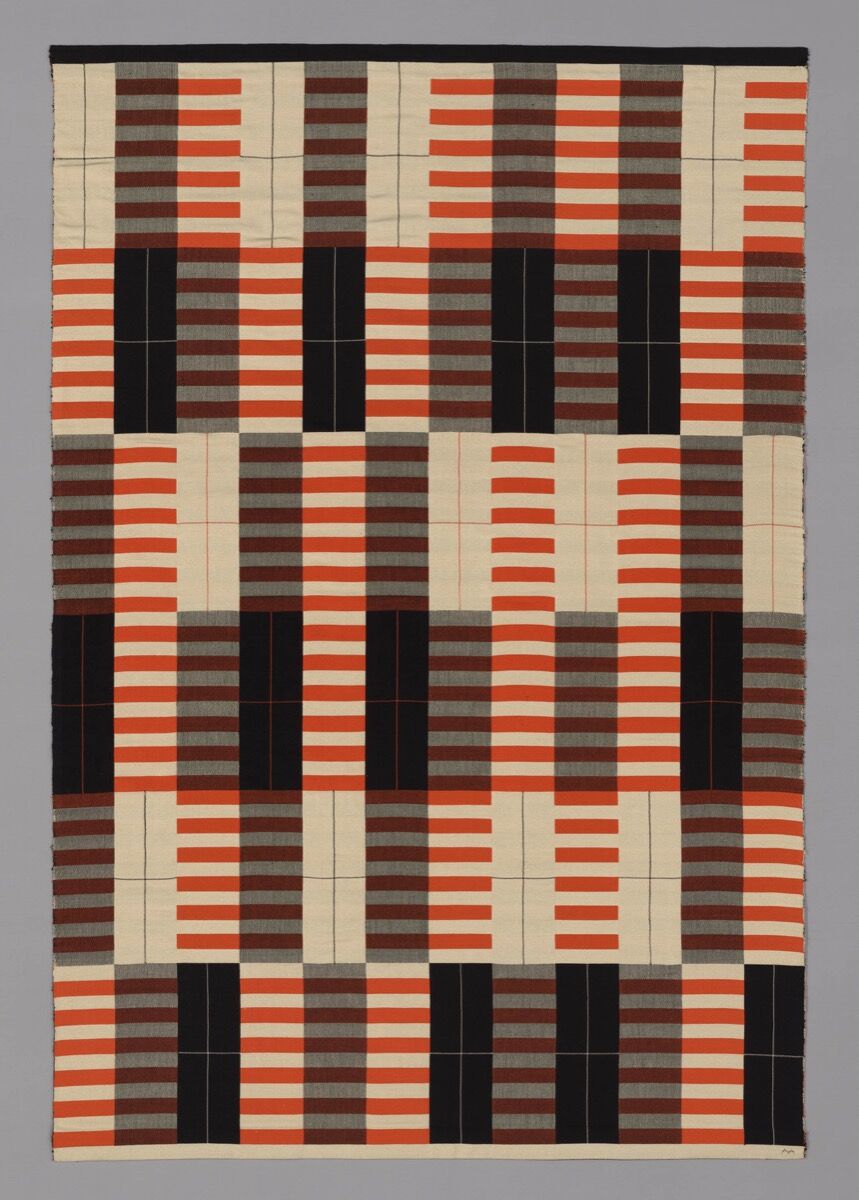

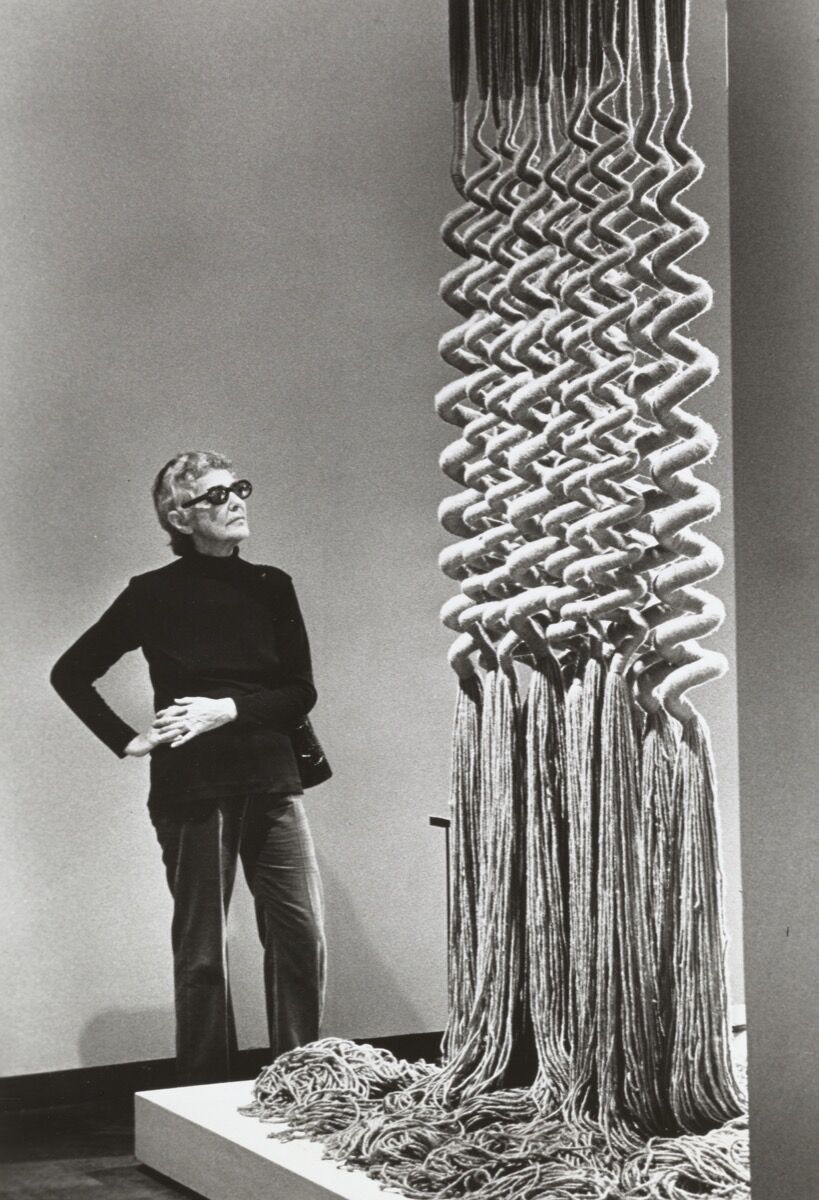

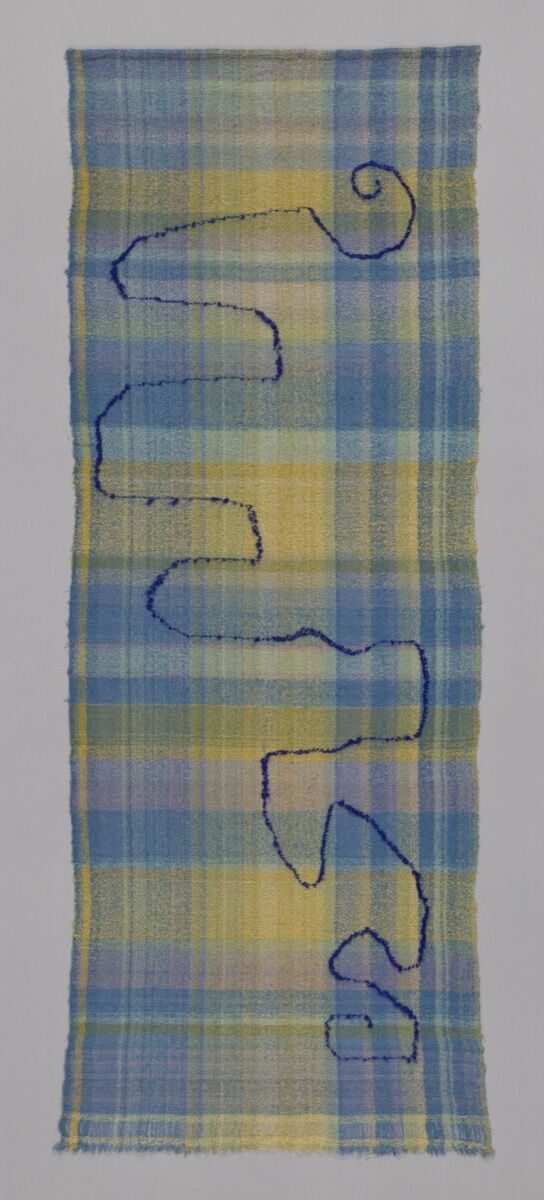

set up Ontos Weaving Workshops in Herrliberg, near Zurich, Switzerland, returned to become the weaving studio's technical director, replacing Helene Börner, and work with Georg Muche, who would remain the form master. Although she was not officially made a junior master until 1927, it was clear both the organization and content of the workshop were under her control. It was obvious from the start, the pairing of Muche and Stölzl was not enjoyed by either side, and resulted in Stölzl running the workshop almost single-handedly from 1926 onward.

The new Dessau campus was equipped with a greater variety of looms and much improved dyeing facilities, which allowed Stölzl to create a more structured environment. Georg Muche brought in Jacquard looms to help intensify production. He saw this as especially important now as the workshops were the school's main source of funding for the new Dessau Bauhaus. The students rejected this and were not happy with the way Muche had used the schools funds. This, among other smaller events, instigated a student uprising within the weaving department. On March 31, 1927, despite some staff objections, Muche left the Bauhaus. With his departure, Stölzl took over both as form master and master crafts person of the weaving studio. She was assisted by many other key Bauhaus women, including Anni Albers, Otti Berger and Benita Otte.

Stölzl began trying to move weaving away from its ‘woman’s work’ connotations by applying the vocabulary used in modern art, moving weaving more and more in the direction of industrial design. By 1928, the need for practical materials was highly stressed and experimentation with materials such as cellophane became more prominent. Stölzl quickly developed a curriculum which emphasized the use of handlooms, training in the mechanics of weaving and dyeing, and taught classes in math and geometry, as well as more technical topics such as weave techniques and workshop instruction. The earlier Bauhaus methods of artistic expression were quickly replaced by a design approach which emphasized simplicity and functionality.

Stölzl considered the workshop a place for experimentation and encouraged improvisation. She and her students, especially Anni Albers, were very interested in the properties of a fabric and in synthetic fibers. They tested materials for qualities such as color, texture, structure, resistance to wear, flexibility, light refraction and sound absorption. Stölzl believed the challenge of weaving was to create an aesthetic that was appropriate to the properties of the material. In 1930, Stölzl issued the first ever Bauhaus weaving workshop diplomas and set up the first joint project between the Bauhaus and the Berlin Polytex Textile company which wove and sold Bauhaus designs. 1In 1931 she published an article entitled “The Development of the Bauhaus Weaving Workshop”, in the Bauhaus Journal spring issue. Stölzl's ability to translate complex formal compositions into hand woven pieces combined with her skill of designing for machine production made her by far the best instructor the weaving workshop was to have. Under Stölzl's direction, the weaving workshop became one of the most successful faculties of the Bauhaus.

Marianne Brandt - Self portrait on mirrored sphere at Bauhaus Dessau - 1929

https://www.facebook.com/…/a.14484696521…/1471766016470168/…

看歐洲幾個電視台:法、英女子多走上街頭;德國電視台和訪問建築教授。多長得很好......

法國自稱是builder王國,其實,頭200年蓋好巴黎聖母院的,是"國際工人".....

20世紀1919~32的德國Bauhaus就是要發揮中世紀的"合作"精神。當時法國繪畫藝術強,驕傲,措失良機。

慶祝Bauhaus 90周年的書,很好,10年老書自有它的魅力。

Eugen Batz

The spatial effect of colours and forms, 1929/30

Tempera over graphite on black paper

30.2 x 32.9 cm

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2009

Bauhaus_ literally means “House of Building” or “Building School”. Back in 1919, in the town of Weimar in Thuringia - Germany the design revolution began. World renowned architect Walter Gropius established an academy to teach up-to-date ideas in color theory, painting, printmaking, pottery, industrial design, interior design, weaving and textiles, typography and graphic design. Nonetheless, despite the school’s name architecture was not taught; students who wished to be educated on building design were sent to work in Gropius’s private architecture office.

Walter Gropius, 1928

in front of his design for the Chicago Tribune Tower of 1922

Photo: Associated Press, Berlin

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

The Bauhaus Masters in 1926

(on the roof of the Bauhaus building, 4 December 1926)

left to right: Josef Albers, Hinnerk Scheper, Georg Muche,

László Moholy-Nagy, Herbert Bayer, Joost Schmidt, Walter Gropius,

Marcel Breuer, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Lyonel Feininger, Gunta Stölzl, Oskar Schlemmer

Photo: unknown

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin / Musée National d’Art Moderne / Centre Pompidou

Today, 90 years later all eyes are on Weimar, Jena and Erfurt as the crucial meeting points of the Bauhaus anniversary. The Bauhaus, was the most important and influential school of design of the 20th century despite the few years of its existence. Till present day the Bauhaus has had a long lasting impact on art, design, architecture and every day life, mostly because of the principle of form. Various classic and influential design objects of the 20th century were developed in Weimar during the Bauhaus from 1919 – 1925.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, 1934

Photo: Werner Rohde

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Contribution ‘Wabe’ (honeycomb) to the idea competition for the skyscraper at the Bahnhof Friedrichstrasse, 1922

Large photograph, supplemented by drawing

140 x 100 cm

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2009

For the occasion of the 90th anniversary of the Bauhaus, as of July 22nd – October 4th 2009 the Modell Bauhaus in Weimar is presenting the exhibition “Berlin // Martin - Gropius - Bau”, where it primary focuses on the early years of the world renown school of design. The aim of this exhibition is to portray Weimar as a laboratory where ideas and thoughts that were conceived subsequently reached a mature state deriving approval worldwide. The innovative approaches and impulse affected the world of design developed at the Bauhaus up till current day.

The exhibit will present well known and less known features of the Bauhaus were the assignments from the school workshops are presented as the highlights, as well as works of the Bauhaus masters. Over 900 objects from international collections will be exhibited including loans from collections of other museums.

Wassily Kandinsky

Untitled (from the portfolio for Walter Gropius on his birthday, 18th May 1924), 1924

Black ink, water colours and opaque colours

19.6 x 22.5 cm

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2009

Marcel Breuer (design and realisation)

Gerhard Oschmann (reconstruction)

Lady’s dressing-table from the Bauhaus experimental house “Am Horn”, Weimar, 1923 / 2004

168 x 126.5 x 48 cm

Photo: Hartwig Klappert, Berlin

Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau

Other events of the exhibition include a five day International Symposium “Global Bauhaus” which will take place on September 21st – September 26th, 2009 at the Martin-Gropius-Bau, Cinema and Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau. The Symposium will focus on the internationalization, the network character of the avant-garde and the migration paths of the Bauhaus and examine the major questions such as: How did the Bauhaus achieve such a world-wide influence and become an exemplary institution? Who were the multipliers of the Bauhaus idea? What does the Bauhaus stand for today? The speakers are worldwide leading architects, artists, design historians, art teachers and cultural scholars who have engaged in the research of the history and influence of the Bauhaus.

Walter Gropius

Work model for the memorial for the “March Heroes”, 1921

Klassik Stiftung Weimar

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2009

Herbert Bayer

Design for the multi-media trade fair stand of a toothpaste manufacturer, 1924

Opaque colours, charcoal, coloured ink, graphite and collage elements on paper

54.6 x 46.8 cm

Harvard University Art Museums, Gift of the artist

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2009

Another interesting event which twenty lucky pupils from partner universities will participate in is the Bauhaus Summer School which will last eight to ten days in mid- September 2009 at Weimar – Dessau – Berlin. They will participate in seminars given by members of the Bauhaus institutions. Emphasis will be placed on the intimate encounter with ideas and artifacts of the Bauhaus at the original locations. To this end, they will be able to visit private homes and work with objects in the Bauhaus collection. The goal of this program is the support of international students in the area of Bauhaus research, the encounter of young people from different cultures, scholarly exchange of ideas and the intensification of project-oriented cooperation.

Marcel Breuer

Club Chair B 3, 2nd version, 1926

Tubular steel, welded transitions and screwed plug and socket connections,

anthracite-coloured wire mesh straps

70.5 x 81 x 69.5 cm; seat 30 cm high;

steel tube diameter 22 mm

Photo: Hartwig Klappert, Berlin

Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau

László Moholy-Nagy

Light Space Modulator, 1922-1930

(1970 replica of the original in the Busch-Reisinger Museum)

Chrome-plated steel, aluminium, glass, plexiglass, wood, electric motor

Height 91 cm

Photo: Hartwig Klappert, Berlin

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2009

Баувху/Bauwchu說這專頁讚

4月14日下午11:04 ·

Alfred Arndt - colour plan for the exteriors of the Dessau Masters’ houses (3 semi-detached houses) - 1926

ARTSY.NET

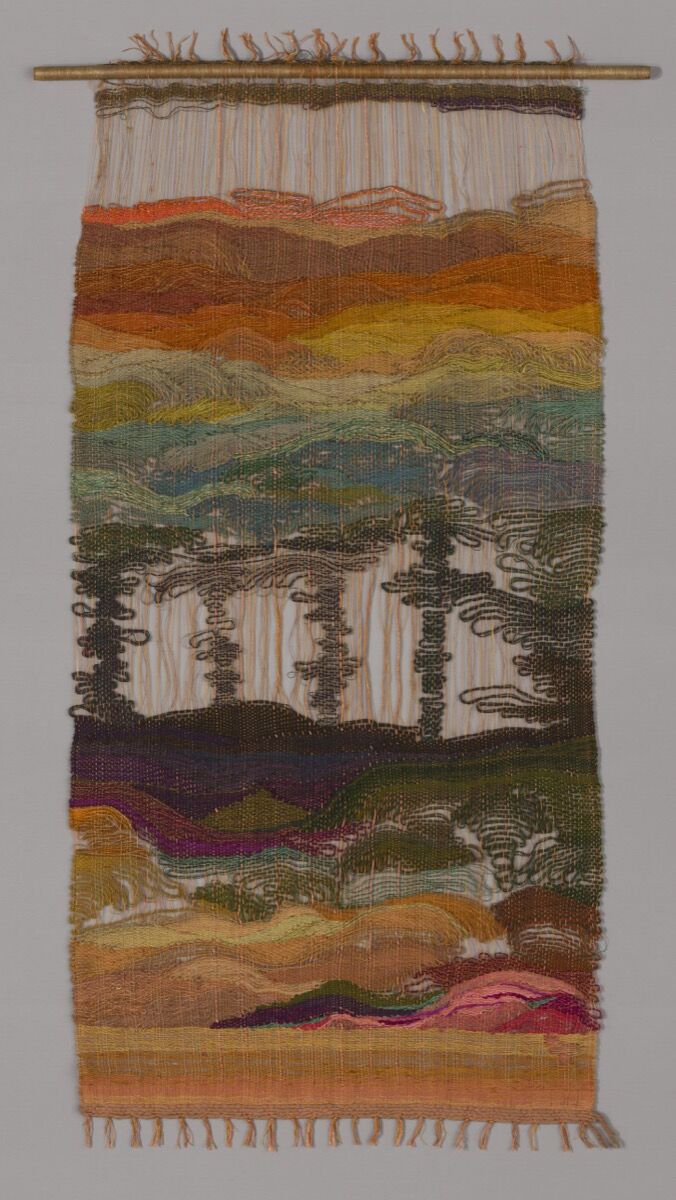

The Women Weavers of the Bauhaus Have Inspired Generations of Textile Artists

沒有留言:

張貼留言