紀念Benedict Anderson: 2013.2.15:今天台北陰雨天 固然《馬雅可夫斯基在夏日別訴墅中的奇遇》多少成追憶 不過 昨夜就給朋友了: (Benedict Anderson的 《比較的幽靈:民族主義、東南亞與世界》(The Spectre of Comparisons: Nationalism, Southeast Asia, and the World)扉頁 引 馬雅可夫斯基((Vladimir Mayakovsky 1893~1930)的)

紀念Benedict Anderson,2015.12.14 知道先生自傳2016年出版。

至善社的小伙子的目標,是要"一直做發動機, 從後面推動年長者"。------Benedict Anderson《比較的幽靈:民族主義、東南亞與世界》4 黑暗之時和光明之時,頁134

Benedict Anderson的 《比較的幽靈:民族主義、東南亞與世界》(The Spectre of Comparisons: Nationalism, Southeast Asia, and the World)扉頁 引 馬雅可夫斯基(Vladimir Mayakovsky ,1893~1930)的 《 馬雅可夫斯基在夏日別墅中的奇遇》(詩題翻譯有點問題): 參考《 馬雅可夫斯基夏天在別墅中的一次奇遇》----這是一首長詩, 作者邀請太陽來長敘,"....咱是天生的一對,....我放射著太陽的光輝,你就讓自己的詩章 散發著光芒......."

時時發光,

處處發光,

永遠叫光芒照耀,

發光----

沒二話說!

這就是我和太陽的

口號!

上述的翻譯有點問題: 據 馬雅可夫斯基(Vladimir Mayakovsky)選集第一卷

第88頁的翻譯如下:

----

鍾老師您好,

黑體字的部分,前者翻譯得較好,「I nikakikh gvozdei!」是俄文俗語片語,意為:夠了、不需多說了、沒什麼好說的了。給您參考。

丘光

*****

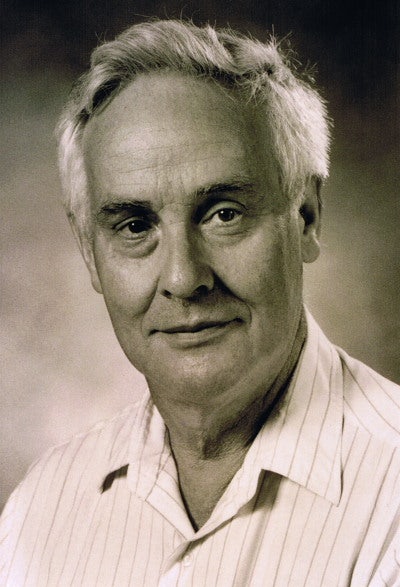

政治學名著《想像的共同體:民族主義的起源與散布》的作者班納迪克.安德森(Benedict Anderson)12日於印尼瑪琅(Malang)逝世,享年79歲。

自由引述 CNN報導提到,安德森的養子育滴提拉(Wahyu Yudistira)表示,安德森在12日晚間11時30分逝世,上週四,安德森還在印尼大學公開講課,育滴提拉說,安德森非常喜歡印尼,但他可能過於疲勞。

納迪克.安德森是康乃爾大學國際研究Aaron L. Binenjorb講座教授,為全球知名的東南亞研究學者,最著名的著作是《想像的共同體》,作者認為民族是「一種想像的政治共同體」,該書自1983年問世以來,被譯成31種語言出版,是社會科學領域必讀的重要作品。

安德森2003年、2010年時曾來訪台灣,對台灣的處境與民族主義發表看法。聯合報導,當時他談到二二八的看法,安德森以愛爾蘭爭取獨立的經驗提醒台灣,「就像愛爾蘭一樣,台灣在過去數百年中承受了許多苦難,然而台灣不應該重到(sic)愛爾蘭的覆轍,長期陷入地方主義和無法忘懷的怨恨之中」,他說「過去絕不應該被遺忘」,但對現在來說,「重要的不是過去的黑暗,而是在前方向我們招手的光明。」

對於當時將慶祝中華民國建國百年,安德森說:「如果我是台灣人,我會問為什麼要慶祝,」他形容兩岸慶祝建國的做法「就像年輕人終日在電腦前凝視自己的臉書,」「與其不斷問『我是誰』,不如去想我可以為未來做麼!」

納迪克.安德森還著有《比較的鬼魂:民族主義、東南亞與全球》(The Spectre of Comparisons: Nationalism, Southeast Asia, and the World)、《革命時期的爪哇》(Java in a Time of Revolution)、《美國殖民時期之暹羅政治與文學》(Literature and Politics in Siam in the American Era)、《語言與權力:探索印尼之政治文化》(Language and Power: Exploring Political Cultures in Indonesia)、《三面旗幟下:無政府主義與反殖民的想像》(Under Three Flags: Anarchism and the Anti-Colonial Imagination)等重要作品。

第88頁的翻譯如下:

永遠照耀,

到處照耀 ,

直到那日月的盡頭,

照耀----

不顧一切阻撓! I nikakikh gvozdei!

這就是我和太陽的

口號!

----

鍾老師您好,

黑體字的部分,前者翻譯得較好,「I nikakikh gvozdei!」是俄文俗語片語,意為:夠了、不需多說了、沒什麼好說的了。給您參考。

丘光

*****

政治學名著《想像的共同體:民族主義的起源與散布》的作者班納迪克.安德森(Benedict Anderson)12日於印尼瑪琅(Malang)逝世,享年79歲。

自由引述 CNN報導提到,安德森的養子育滴提拉(Wahyu Yudistira)表示,安德森在12日晚間11時30分逝世,上週四,安德森還在印尼大學公開講課,育滴提拉說,安德森非常喜歡印尼,但他可能過於疲勞。

納迪克.安德森是康乃爾大學國際研究Aaron L. Binenjorb講座教授,為全球知名的東南亞研究學者,最著名的著作是《想像的共同體》,作者認為民族是「一種想像的政治共同體」,該書自1983年問世以來,被譯成31種語言出版,是社會科學領域必讀的重要作品。

安德森2003年、2010年時曾來訪台灣,對台灣的處境與民族主義發表看法。聯合報導,當時他談到二二八的看法,安德森以愛爾蘭爭取獨立的經驗提醒台灣,「就像愛爾蘭一樣,台灣在過去數百年中承受了許多苦難,然而台灣不應該重到(sic)愛爾蘭的覆轍,長期陷入地方主義和無法忘懷的怨恨之中」,他說「過去絕不應該被遺忘」,但對現在來說,「重要的不是過去的黑暗,而是在前方向我們招手的光明。」

對於當時將慶祝中華民國建國百年,安德森說:「如果我是台灣人,我會問為什麼要慶祝,」他形容兩岸慶祝建國的做法「就像年輕人終日在電腦前凝視自己的臉書,」「與其不斷問『我是誰』,不如去想我可以為未來做麼!」

納迪克.安德森還著有《比較的鬼魂:民族主義、東南亞與全球》(The Spectre of Comparisons: Nationalism, Southeast Asia, and the World)、《革命時期的爪哇》(Java in a Time of Revolution)、《美國殖民時期之暹羅政治與文學》(Literature and Politics in Siam in the American Era)、《語言與權力:探索印尼之政治文化》(Language and Power: Exploring Political Cultures in Indonesia)、《三面旗幟下:無政府主義與反殖民的想像》(Under Three Flags: Anarchism and the Anti-Colonial Imagination)等重要作品。

Centaur: the life and art of Ernst Neizvestny - Page 56 - Google Books Result

books.google.com/books?isbn=0742520587

Albert Leong - 2002 - Biography & Autobiography

... always, to shine everywhere do dnei poslednikh dontsa, to the last drops of one's days, svetit' i nikakikh gvozdei to shine and no nails Vot lozung moi i solntsa.

《比較的幽靈:民族主義、東南亞與世界》(The Spectre of Comparisons: Nationalism, Southeast Asia, and the World)

出版日期:2012年本書分析了形成民族主義的各種力量,考察各個東南亞國家具體的民族主義表現並加以比較,最後提出為在冷戰後遭受冷遇的民族主義正名,對東南亞、殖民主義和民族主義都有深刻的洞見。 “人文與社會譯叢”秉承“激活思想,傳承學術”之宗旨,以精良的選目,可靠的譯文,贏得學術界和公眾的廣泛認可與好評,被認為是當今“最好的社科叢書之一”。

目錄 · · · · · ·

目錄題記致謝導論第一部分民族主義的長弧

1 民族主義、認同與序列邏輯

2 複製品、光暈和晚近的民族主義想像

3 遠距民族主義第二部分東南亞:國別研究

4 黑暗之時和光明之時

5 專業夢想

6 雅加達鞋裡的沙子

7 撤退症狀

8 現代暹羅的謀殺與演進

9 菲律賓的地方巨頭民主制

10 第一個菲律賓人

11 難以想像第三部分東南亞:比較研究

12 東南亞的選舉

13 共產主義之後的激進主義

14 各尋生路

15 多數族群和少數族群第四部分所餘何物?

16 倒霉的國家

17民族之善索引·

1 民族主義、認同與序列邏輯

2 複製品、光暈和晚近的民族主義想像

3 遠距民族主義第二部分東南亞:國別研究

4 黑暗之時和光明之時

5 專業夢想

6 雅加達鞋裡的沙子

7 撤退症狀

8 現代暹羅的謀殺與演進

9 菲律賓的地方巨頭民主制

10 第一個菲律賓人

11 難以想像第三部分東南亞:比較研究

12 東南亞的選舉

13 共產主義之後的激進主義

14 各尋生路

15 多數族群和少數族群第四部分所餘何物?

16 倒霉的國家

17民族之善索引·

《比較的幽靈》試讀:序言

----

"群體史縮斂成一故事是特別重要的。秉持此一精神,Benedict Anderson (1991)論到,國家感牽涉到建立在透過一遺忘,發明,和詮釋的審慎結合所建構的歷史之想像共同體的了解。" James March (2010)

Benedict Anderson, Man Without a Country

The scholar of nationalism and author of ‘Imagined Communities’ has died at the age of 79.

BY JEET HEER

December 14, 2015

Signal

If Anderson had a homeland, it was Indonesia, which he threw his whole heart and mind into not just studying, but also emotionally inhabiting.

JEET HEER

Benedict Anderson, who died yesterday at age 79 in Malang, Indonesia, is internationally famous for his 1983 book Imagined Communities, far and away the most influential study of nationalism. Unlike earlier scholars who took a negative view of the subject, Anderson saw nationalism as an integrative imaginative process that allows us to feel solidarity for strangers. “In an age when it is so common for progressive, cosmopolitan intellectuals (particularly in Europe?) to insist on the near-pathological character of nationalism, its roots in fear and hatred of the Other, and its affinities with racism, it is useful to remind ourselves that nations inspire love, and often profoundly self-sacrificing love,” Anderson wrote in Imagined Communities. “The cultural products of nationalism—poetry, prose fiction, music, plastic arts—show this love very clearly in thousands of different forms and styles.”

For a scholar of nationalism, it is surprisingly difficult to say what nation Benedict Anderson belonged to. Anderson was a peripatetic child of the British Empire. Born in 1936 in Kunming, China, where his Anglo-Irish father worked for Chinese Maritime Customs, an imperial consortium that collected taxes, the Andersons had to flee to California in 1941 when the Japanese Empire began to expand into the country. The family returned to Ireland in 1945, but occupied an ambiguous position in their ancestral land. One strand of the family had been Irish nationalists of long-standing, but as Anglo-Irish they existed as a privileged minority, enjoying prestige but often excluded from the nation’s core Catholic identity.

If the Andersons weren’t quite Irish, they weren’t completely English either. The family’s experience in China gave them appreciation for the underside of Empire. As Perry Anderson, Benedict’s younger brother and himself a distinguished historian, once noted, their father’s experience fighting corruption in the colonial management of China left a lasting mark on the children. In 1956, as an undergraduate at Cambridge, Benedict Anderson was radicalized by the protests over the Suez crisis, where he found himself taking sides with anti-imperialist students—many of them born, like him, in the formerly colonized world—against British nationalists who supported the Anglo-French attempt to seize the Suez Canal. Out of his Cambridge experience, Anderson started on the path to becoming a Marxist and an anti-colonialist scholar.

After Cambridge, Anderson attended Cornell for graduate school and immersed himself in the study of Indonesia. While Anderson spent much of his life in the United States, it wasn’t quite accurate to say that he became an American. In truth, if Anderson had a homeland, it was Indonesia, which he threw his whole heart and mind into not just studying, but also emotionally inhabiting.

Anderson’s linguistic fluency was almost superhuman. Perry Anderson could read all the major European languages but once ruefully declared his big brother was the true polyglot of the family: Benedict could read Dutch, German, Spanish, Russian, and French and was fully conversant in Indonesian, Javanese, Tagalog, and Thai; he claimed he often thought in Indonesian. (The ability to acquire languages ran in the family—Melanie Anderson, an anthropologist and the younger sister of Perry and Benedict, is fluent in Albanian, Greek, Serbo-Croatian).

An Indonesian friend of mine once marveled that Benedict Anderson was so at ease in Javanese that he could tell jokes in the language. The friend also favorably compared Anderson with another great expert on Indonesia, the anthropologist Clifford Geertz. “I always profit from reading Geertz but he simply deepens my understanding of Indonesia,” my friend said. “Anderson makes me see things about Indonesia that I never noticed. He knows Indonesia as well as any Indonesian.”

Between 1965 and 1966, Indonesia was engulfed in counter-revolutionary violence that led to the American-supported anti-Communist dictator Suharto taking power in 1967. Between 600,000 and one million Indonesians, most of them supporters of the nation’s largest communist party, were killed by the resulting purge. The Central Intelligence Agency, which actively participated in helping the Indonesian military choose targets, called it in a 1968 declassified study “one of the worst mass murders of the twentieth century.”

The violence of Suharto’s coup was a key turning point in Anderson’s life. It “felt like discovering that a loved one is a murderer,” he wrote. He threw himself into the cause of chronicling the true history of the coup and to countering the propaganda of the Suharto regime. While at Cornell in 1966, Anderson and his colleagues anonymously authored “The Cornell Paper,” a report which became a key document in debunking the official account of the coup, and which was circulated widely in Indonesian dissident circles. Anderson was also one of the only two foreign witnesses at the 1971 show trial of Sudisman, the general secretary of the Indonesian communist party, who was sentenced to death. Anderson would later translate and publish Sudisman’s testimony, another key text in Indonesian history.

In 1972, Anderson was expelled from Indonesia, becoming an exile from the nation he made his own. He would return to Indonesia only in 1998, after the overthrow of the Suharto regime. After a brief private visit to friends, Anderson had an emotionally charged public event sponsored by the leading Indonesian paper Tempo.

In a brilliant article in the magazine Lingua Franca, the journalist Scott Sherman described Anderson’s return to Indonesia:

At a luxury hotel in downtown Jakarta, the sixty-two-year-old Anderson, wearing a light shirt and slacks to combat the stifling heat, faced a tense, expectant audience of three hundred generals, senior journalists, elderly professors, former students, and curiosity seekers. In fluent Indonesian, he lashed the political opposition for its timidity and historical amnesia—especially with regard to the massacres of 1965-1966.

During his return to Indonesia, Anderson was reunited with a young Chinese communist who had been on trial with Sudisman. Anderson had thought this young man had been killed with Sudisman. His miraculous survival was one sign that the Suharto regime hadn’t destroyed everything.

Anderson’s most famous work, Imagined Communities, emerged from the the crucible of Indonesian history. How do diverse nations like Indonesia, made up of many languages and ethnicities, hold together? Why do they sometimes fall apart? What keeps people in large nations from killing each other and why does national cohesion sometime fail? These weren’t abstract questions for Anderson, but were instead born out of lived immersion in Indonesian history.

While Imagined Communities is Anderson’s best-known work, everything he wrote is worth reading—there are few more thoughtful studies of transnational terrorism than his Under Three Flags: Anarchism and the Anti-Colonial Imagination (2005). As well-versed in novels and poetry as he was in scholarship, Anderson was an eloquent advocate for global culture, calling attention to the literatures of Indonesia and the Philippines. A world traveler, it is fitting that Benedict Anderson died in Indonesia, a country he could truly call home.

Jeet Heer is a senior editor at the New Republic.

統獨人士必讀:《想像的共同體》Benedict Anderson/著 吳睿人/譯 (1999 時報)

Benedict Anderson第一次來台灣的演講,我參與過。

沒有留言:

張貼留言