"The Idiot" by Fyodor Dostoevsky is an immortal masterpiece, a novel that deals with deep and complex themes.

The protagonist, Prince Myshkin, returns to Russia after being in a sanatorium to treat his illness: epilepsy. Aware of the transience of life and the pain that often accompanies it, our Prince, pure of heart, will be kind and compassionate to everyone he meets, without asking for anything in return. However, kindness often causes the world to take advantage of those who practice it with conviction. When the Prince falls madly in love with Nastas'ja Filippovna, a beautiful woman of dubious reputation, the plot becomes complicated. Nastas'ja Filippovna, who supports herself by living in luxury thanks to the men she frequents, will try to prevent Myshkin from compromising himself for a love that is not worthy of him. The tragic ending reveals how the fragile balance between good and evil always tips towards the latter.

"The Idiot" explores innocence and purity of spirit in a greedy and corrupt world. Prince Myshkin, with his disarming goodness, represents a rare bird destined for defeat. Despite the underlying pessimism, the novel is enjoyable and fascinating. Dostoevsky paints a corrupt, ambitious and cruel Russia, in stark contrast to Myshkin's good soul.

A work that deserves to be read and reflected upon. Its stylistic elegance, the depth of the characters and the central theme make this novel a timeless masterpiece.

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky was born in Moscow** on November 11, 1821. The son of a military doctor and a mother from a noble and very religious family, Dostoevsky was intended for a military career. However, his true passion was literature. After completing his studies in military engineering, he gave up his career and wrote his first novel, "Poor Folk," which achieved great success. Throughout his life, Dostoevsky produced a series of psychological works that explored the complexities of the human condition. Among his best-known masterpieces are "Crime and Punishment," "The Brothers Karamazov," and "The Idiot." His life was marked by personal challenges, including epileptic seizures and a period of exile in Siberia. Despite these hardships, Dostoevsky remains one of the greatest novelists in Russian literature.

。。。

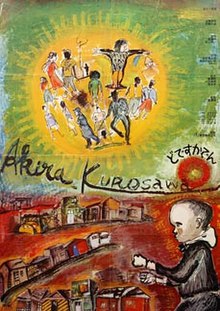

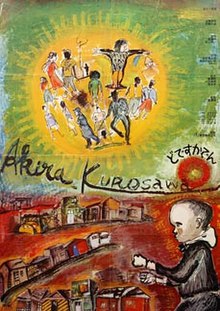

Akira Kurosawa 1910-98 Ikiru (生きる, "To Live") 1952 Director: Akira Kurosawa Adapted from: The Death of Ivan Ilyich

Ikiru (生きる, "To Live") 1952

Director: Akira Kurosawa

Adapted from: The Death of Ivan Ilyich

#ikiru #AkiraKurosawa #moviequotes

堅持寫(劇)作下去 (一個字一個字累積),效法巴爾札克;多讀 (也要讀經典),多經歷,記憶是創作之源,人無法無中生有。

Akira Kurosawa's Advice To Aspiring Filmmakers

李怡

黑澤明之所以偉大的原因

——黑澤明自傳《蝦蟆的油》(一分鐘閱讀書籍)

武士帶着他的妻子走在竹林中,強盜出來把他綁起來,強暴了他的妻子,武士也喪生了。這個情節,由強盜、妻子和武士的鬼魂說來,儘管大體一樣,但因細節相異而呈現截然不同的真相。這是日本作家芥川龍之介的小說《竹林中》,1951年由日本導演黑澤明改編成電影取名《羅生門》,從此,羅生門就成為同一件事各有各說法而無法知道真相的代名詞。

在上世紀被稱為「黑澤天皇」的導演黑澤明,不僅是我的電影偶像,而且是我的文學藝術的偶像。電影《羅生門》赤裸裸暴露了,因人性的虛飾而使世上的事情幾乎沒有真相,而這種虛飾的人性又幾乎無人可以避免,這種揭示使我大受觸動。這以後,幾乎黑澤明所有的電影我都沒有錯過。他的《七俠四義》、《用心棒》、《天國與地獄》、《赤鬍子》、《德蘇烏扎拉》、《影武者》,每一部我都被扣動心弦,他的人道主義精神也深深影響我的寫作。

早前讀到他的自傳《蝦蟆的油》,我再一次被他深刻自剖所打動。

黑澤明1910年生於東京,1951年以《羅生門》獲得威尼斯影展金獅獎,隔年再拿下奧斯卡最佳外語片獎。1975年以《德蘇烏扎拉》二度獲得奧斯卡。1990年獲奧斯卡終身成就獎。1998年病逝東京,享壽八十八歲。1999年經CNN評選為二十世紀亞洲最有貢獻人物(藝文類)。

黑澤明的自傳《蝦蟆的油》,中譯本副題是「黑澤明尋找黑澤明」。這本自傳是1978年他68歲時寫的,那時他所有傑作已獲得全世界電影界肯定,距離他成名作《羅生門》問世也接近30年了。

這本書從他光著身體來到這世界寫起,記下家庭、學校、戰爭、入影圈,從助導、編劇到當上導演,及拍好幾部戲的種種記事。不過,寫到最後一章「直到《羅生門》」,這本書就結束,沒有往下寫。也就是說,以後他在電影業的輝煌成就,他在1951年後30年拍出許多傑作的經過,他都不寫了。

甚麼原因?在他的自傳中,他說正是因為《羅生門》這部偉大作品,影響他無法寫下他其後的人生。

在黑澤明自傳中,他講到籌拍這部戲的時候,受到電影製作公司的社長反對。

開拍前一天,公司派給他的三個助導去找他,說完全看不懂這個劇本,要求黑澤明作說明。黑澤簡單說明電影的主題是:「人不能老實面對自己,不能毫無虛矯地談論自己。這個劇本,就是描述人若無虛飾就活不下去的本性。不對,是描述人到死都不能放下虛矯的深罪。這是人與生俱來、無可救藥的罪業,是人的利己之心展開的奇怪畫卷。如果把焦點對準人心不可解這一點,應該可以了解這個劇本。」

聽了他的解釋,其中兩個助導說回去再看一遍劇本試試,但總助導還是不能接受,終辭任這職位。不過其他人,包括演員都非常熱心地投入拍攝工作。電影拍成上映,在日本沒有甚麼反響,而黑澤明與電影公司的再合作計劃也被拒絕。

有一天,黑澤明回家,老婆衝出來告訴他:《羅生門》在威尼斯影展獲金獅獎。他感到愕然,因為他連這部戲被拿去參展都不知道。事實上不是日本製作公司拿去參展,而是有一個意大利影評人在日本看了這部片交由意大利電影公司推薦參展的。這次獲獎和隨後在奧斯卡獲獎,對日本電影界猶如晴天霹靂。日本人為甚麼對日本的存在這麼沒有自信?為甚麼尊重外國的東西,卻卑賤日本的東西呢?黑澤只能說,這是可悲的國民性。

獲獎使電影在日本重被重視,電視也予以播放。在電視播出時,電視台訪問了原製作公司的社長,這個社長得意洋洋地說,是他自己一手推動這部作品的。黑澤看了說不出話來。因為當初拍這部片時,社長明明面有難色,說這是甚麼讓人看不下去的東西,而且把推動這部作品的高層和製片降職。社長還滔滔不絕地重複外國影評誇獎這部片的攝影技術,說這部片第一次把攝影機面對太陽拍攝。而直到採訪最後,他都沒有提到黑澤明和攝影師宮本的名字。

黑澤看了這段訪問,覺得簡直就是《羅生門》啊。 電影《羅生門》本身,固然表現了可悲的人性,而在獲獎及在電視播出時,也呈現出同樣的人性。

他再次知道,人有本能地美化自己的天性,人很難如實地談論自己。可是,黑澤說,他不能嘲笑這位社長。他反省說:「我寫這本自傳,裏面真的都老老實實寫我自己嗎?是否沒有觸及自己醜陋的部分?是否或大或小美化了自己?寫到《羅生門》無法不反省。於是筆尖無法繼續前進。《羅生門》雖然把我以電影人的身份送出世界之門,但寫了自傳的我,無法從那扇門再往前寫。」

黑澤明以真誠的心,奉獻了芥川龍之介的人性之作,而創作《羅生門》的過程和結果,也創造了黑澤明自己。在創造了許多被世界肯定的傑作之後,仍然能夠如此真誠地反省自己。我們終於知道黑澤明之所以偉大的原因了,就是他有與眾不同的內在反省能力。是不是每個人都無法擺脫這種不能如實談論自己的虛飾的人性呢?常說要忠於自己的人,包括我在內,真要好好想一想。

The Sea Is Watching Buy this Movie

Madadayo Buy this Movie

Rhapsody in August Buy this Movie

Akira Kurosawa's Dreams Buy this Movie

Ran Buy this Movie

Kagemusha Buy this Movie

Dersu Uzala

Akira Kurosawa on set

Born 23 March 1910(1910-03-23)

Shinagawa, Tokyo, Japan

Died 6 September 1998 (aged 88)

Setagaya, Tokyo, Japan

Occupation film director, screenwriter, editor, film producer

Years active 1936–1993

Spouse(s) Yōko Yaguchi (1921–1985)

Youth Akira Kurosawa was born to Isamu and Shima Kurosawa on 23 March 1910.[2] He was the youngest of eight children born to the Kurosawas in a suburb of Tokyo.[3] Shima Kurosawa was 40 years old at the time of Akira's birth and his father Isamu was 45. Akira Kurosawa grew up in a household with three older brothers and four older sisters. Of his three older brothers, one died before Akira was born and one was already grown and out of the household. One of his four older sisters had also left the home to begin her own family before Kurosawa was born. Kurosawa's next-oldest sibling, a sister he called "Little Big Sister," also died suddenly after a short illness when he was 10 years old.

Kurosawa's father worked as the director of a junior high school operated by the Japanese military and the Kurosawas descended from a line of former samurai. Financially, the family was above average. Isamu Kurosawa embraced western culture both in the athletic programs that he directed and by taking the family to see films, which were then just beginning to appear in Japanese theaters. Later, when Japanese culture turned away from western films, Isamu Kurosawa continued to believe that films were a positive educational experience.

In primary school, Kurosawa was encouraged to draw by Tachikawa, a teacher who took an interest in mentoring his talents. Both Tachikawa and his brother Heigo had a profound impact on him.[3] Heigo was very intelligent and won several academic competitions but also had what was later called a cynical or dark side. In 1923, the Great Kantō earthquake destroyed Tokyo and left 100,000 people dead. In the wake of this event, Heigo, 17, and Akira, 13, made a walking tour of the devastation. Corpses of humans and animals were piled everywhere. When Akira would attempt to turn his head away, Heigo urged him not to. According to Akira, this experience would later instruct him that to look at a frightening thing head-on is to defeat its ability to cause fear.[4]

Heigo eventually began a career as a benshi in Tokyo film theaters. Benshi narrated silent films for the audience and were a uniquely Japanese addition to the theater experience. In the transition to talking pictures, later in Japan than elsewhere, benshi lost work all over the country. Heigo organized a benshi strike that failed. Akira was likewise involved in labor-management struggles, writing several articles for a radical newspaper while improving and expanding his skills as a painter and reading literature.

When Akira Kurosawa was in his early 20s, his older brother Heigo committed suicide. Four months later, the oldest of Kurosawa's brothers also died, leaving Akira, at age 23, as the only surviving son of an original four.

Personal life Kurosawa's wife was actress Yoko Yaguchi.[5] He had two children with her: a son named Hisao (who became a producer and worked with his father on the films Ran, Dreams, Rhapsody in August, and Madadayo)[6] and a daughter named Kazuko.

Early career

Rashomon poster In 1936, Kurosawa learned of an apprenticeship program for directors through a major film studio, PCL (later Toho).[7] He was hired and worked as an assistant director to Kajiro Yamamoto. After his directorial debut with Sanshiro Sugata (1943), his next few films were made under the watchful eye of the wartime Japanese government and sometimes contained nationalistic themes. For instance, The Most Beautiful (1944) is a propaganda film about Japanese women working in a military optics factory. Sanshiro Sugata Part II (1945) portrays Japanese judo as superior to western (American) boxing.

Rashomon poster In 1936, Kurosawa learned of an apprenticeship program for directors through a major film studio, PCL (later Toho).[7] He was hired and worked as an assistant director to Kajiro Yamamoto. After his directorial debut with Sanshiro Sugata (1943), his next few films were made under the watchful eye of the wartime Japanese government and sometimes contained nationalistic themes. For instance, The Most Beautiful (1944) is a propaganda film about Japanese women working in a military optics factory. Sanshiro Sugata Part II (1945) portrays Japanese judo as superior to western (American) boxing.

His first post-war film No Regrets for Our Youth (1946), by contrast, is critical of the old Japanese regime and is about the wife of a left-wing dissident who is arrested for his political leanings. Kurosawa made several more films dealing with contemporary Japan, most notably Drunken Angel (1948) and Stray Dog (1949). However, it was the period film Rashomon (1950) which led to him being known internationally and won him the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival.[8]

Directorial approach Kurosawa had a distinctive cinematic technique, which he had developed by the 1950s. He liked using telephoto lenses for the way they flattened the frame. He believed that placing cameras farther away from his actors produced better performances as they would not be conscious of the camera. He also liked using multiple cameras, which allowed him to shoot an action scene from different angles. As with the use of telephoto lenses, the multiple-camera technique also prevented Kurosawa's actors from "figuring out which one is shooting him [and invariably turning] one-third to halfway in its direction."[9] Another Kurosawa trademark was the use of weather elements to heighten mood; for example, the heavy rain in the opening scene of Rashomon and the final battle in Seven Samurai (1954); the intense heat in Stray Dog; the cold wind in Yojimbo (1961); the snow in Ikiru (1952); and the fog in Throne of Blood (1957). Kurosawa also liked using frame wipes, sometimes cleverly hidden by motion within the frame, as a transition device.

He was known as "Tenno", literally "Emperor", for his dictatorial directing style. He was a perfectionist who spent enormous amounts of time and effort to achieve the desired visual effects. For the rainstorm scenes in Rashomon, because the falling water (provided by fire trucks) did not show up on film against the sky, he dyed the water black with calligraphy ink in order to achieve the effect of heavy rain.[10] In the final scene of Throne of Blood, in which Mifune is shot by arrows, Kurosawa used real arrows shot by expert archers from a short range, landing within centimetres of Mifune's body.[11] In Ran (1985), an entire castle set was constructed on the slopes of Mt. Fuji only to be burned to the ground in a climactic scene.[12]

Other stories include demanding a stream be made to run in the opposite direction in order to get a better visual effect, and having the roof of a house removed, later to be replaced, because he felt the roof's presence to be unattractive in a short sequence filmed from a train.

His perfectionism also showed in his approach to costumes: he felt that giving an actor a brand new costume made the character look less than authentic. To resolve this, he often gave his cast their costumes weeks before shooting was to begin and required them to wear them on a daily basis and "bond with them." In some cases, such as with Seven Samurai, where most of the cast portrayed poor farmers, the actors were told to make sure the costumes were worn down and tattered by the time shooting started.

Kurosawa did not believe that "finished" music went well with film. When choosing a musical piece to accompany his scenes, he usually had it stripped down to one element (e.g., trumpets only). Only towards the end of his films are more finished pieces heard.

Unusual among directors, Kurosawa edited his films himself during production. After each day's shooting he would go to the cutting room and cut the dailies.[11]

Influences A notable feature of Kurosawa's films is the breadth of his artistic influences. Some of his plots are based on William Shakespeare's works: Ran is loosely based on King Lear, Throne of Blood is based on Macbeth, while The Bad Sleep Well (1960) parallels Hamlet, but is not affirmed to be based on it. Kurosawa also directed film adaptations of Russian literary works, including The Idiot (1951) by Dostoevsky (his favorite author) and The Lower Depths (1957), from the play by Maxim Gorky. Ikiru was inspired by Leo Tolstoy's The Death of Ivan Ilyich. Dersu Uzala (1975) was based on the 1923 memoir of the same title by Russian explorer Vladimir Arsenyev. Story lines in Red Beard (1965) can be found in The Insulted and Humiliated by Dostoevsky.

High and Low (1963) was based on King's Ransom by American crime writer Ed McBain. Yojimbo may have been based on Dashiell Hammett's Red Harvest and also borrows from American Westerns. Kurosawa was very fond of Georges Simenon and Stray Dog was a product of Kurosawa's desire to make a film in Simenon's manner.[13]

Cinematic influences include Frank Capra, William Wyler, Howard Hawks, his mentor Kajiro Yamamoto, and his favorite director John Ford,[14] whose habit of wearing dark glasses Kurosawa emulated. When Kurosawa met Ford, the American simply said, "You really like rain." Kurosawa responded, "You've really been paying attention to my films."[15] He would later instruct Yoshio Tsuchiya, one of the actors in Seven Samurai, to retrieve the same hat Ford wore during that meeting.[16]

Despite criticism by some Japanese critics that Kurosawa was "too Western,"[17] he was deeply influenced by Japanese culture as well, such as the Noh theaters and the Jidaigeki (period drama) genre of Japanese cinema.

Influence Seven Samurai was remade as The Magnificent Seven (1960)[18]. Seven Samurai is also considered the progenitor of the "men on a mission" film, popularized by films such as The Dirty Dozen (1967) and The Guns of Navarone (1961). The film is also recognized for popularizing the use of slow-motion in action films/sequences.

Rashomon was remade by Martin Ritt in 1964's The Outrage. Several films and television programs have also come to use what is known as the Rashomon effect, wherein various people give opposing or contrasting accounts of an event; these films include, but are not limited to Vantage Point, Courage Under Fire, Hero, Hoodwinked, and The Usual Suspects. Tajomaru, a film that centers on the eponymous character from Rashomon, was released in 2009.

Yojimbo was unofficially remade as the Sergio Leone western A Fistful of Dollars (1964) (resulting in a successful lawsuit by Kurosawa)[19] and was remade as the prohibition-era film Last Man Standing (1996). Sanjuro was remade in 2007 as Tsubaki Sanjuro, directed by Yoshimitsu Morita.

The Hidden Fortress (1957) was remade as The Last Princess (2008) and is an acknowledged influence on George Lucas's Star Wars films, in particular Episodes IV and VI and most notably in the characters of R2-D2 and C-3PO.[20][21] As well as using a modified version of Kurosawa's signature wipe transition, it has been observed that specific scenes from various Kurosawa films have been emulated throughout George Lucas's Star Wars saga.[21]

Remakes for Ikiru[22] and High and Low[23] are in progress. Second remakes for Rashomon and Seven Samurai are also on the way.[24][25]

The following directors either were directly influenced by Kurosawa, or greatly admired his work:

Satyajit Ray[citation needed] - the great Indian director (famous for his Apu trilogy) and winner of Oscar Lifetime Achievement award.

Andrei Tarkovsky[26][27]

Ingmar Bergman[28] - "Now I want to make it plain that The Virgin Spring must be regarded as an aberration. It's touristic, a lousy imitation of Kurosawa."[29]

Federico Fellini[30] - Having only seen Seven Samurai from Kurosawa's oeuvre, he still thought Kurosawa was the "the greatest living example of what an author of the cinema should be."[31]

Bernardo Bertolucci - "Kurosawa's movies and La Dolce Vita, Fellini, are the things that pushed me sucked into being a film director."[32]

Robert Altman[33][34]

Sidney Lumet - "Kurosawa never affected me directly in terms of my own movie-making because I never would have presumed that I was capable of that perception and that vision."[35]

Sam Peckinpah - "I'd like to be able to make a Western like Kurosawa makes Westerns."[36]

Roman Polanski[37]

Steven Spielberg[38] - "the pictorial Shakespeare of our time"[39]

Martin Scorsese[38] - "His influence on filmmakers throughout the entire world is so profound as to be almost incomparable."[39]

George Lucas[21][38]

Francis Ford Coppola[40] - "One thing that distinguishes Akira Kurosawa is that he didn't make a masterpiece or two masterpieces, he made, you know, eight masterpieces."[41]

Zhang Yimou - "Other filmmakers have more money, more advanced techniques, more special effects. Yet no one has surpassed him."[42]

John Milius[43]

Takeshi Kitano - "...the ideal definition of cinema: a succession of perfect images. And Kurosawa is the only director who has attained that."[44]

John Woo[45][46] - "I love Kurosawa’s movies, and I got so much inspiration from him. He is one of my idols and one of the great masters"[47]

Werner Herzog[48] - "Of the filmmakers with whom I feel some kinship Griffith, Murnau, Pudovkin, Buñuel and Kurosawa come to mind. Everything these men did has the touch of greatness."[49]

Antoine Fuqua[50]

Alex Cox[51]

Arthur Penn[52][53]

Spike Lee[citation needed]

Sergio Leone

Collaboration During his most productive period, from the late 40s to the mid-60s, Kurosawa often worked with the same group of collaborators. Fumio Hayasaka composed music for seven of his films — notably Rashomon, Ikiru and Seven Samurai. When Hayasaka died, he collaborated with composer Masaru Satō, who scored most of his later films. Kurosawa worked with the same five scriptwriters during his career: Eijiro Hisaita, Ryuzo Kikushima, Shinobu Hashimoto, Hideo Oguni, and Masato Ide.[54] Yoshiro Muraki was Kurosawa's production designer or art director for most of his films after Stray Dog in 1949, and Asakazu Nakai was his cinematographer on 11 films including Ikiru, Seven Samurai and Ran. Kurosawa also liked working with the same group of actors, especially Takashi Shimura, Tatsuya Nakadai, and Toshirō Mifune. His collaboration with the latter, which began with 1948's Drunken Angel and ended with 1965's Red Beard, is one of the most famous director-actor collaborations in cinema history.

Later films The film Red Beard marked a turning point in Kurosawa's career in more ways than one. In addition to being his last film with Mifune, it was his last in black-and-white. It was also his last as a major director within the Japanese studio system making roughly a film a year. Kurosawa was signed to direct a Hollywood project, Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970) but 20th Century Fox replaced him with Toshio Masuda and Kinji Fukasaku before it was completed.[55] His next few films were to be significantly more difficult to finance and were made at intervals of five years. The first, Dodesukaden (1970), about a group of poor people living around a rubbish dump, was not a commercial or financial success.

After an attempted suicide, Kurosawa went on to make several more films, although he had great difficulty in obtaining domestic financing despite his international reputation. Dersu Uzala, made in the Soviet Union and set in Siberia in the early 20th century, was the only Kurosawa film made outside of Japan and not in the Japanese language. It is about the friendship of a Russian explorer and a nomadic hunter, and won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. Kagemusha (1980), financed with the help of the director's most famous admirers, George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola, is the story of a man who is the body double of a medieval Japanese lord and takes over his identity after the lord's death. The film was awarded the Palme d'Or (Golden Palm) at the 1980 Cannes Film Festival (shared with Bob Fosse's All That Jazz). Ran was the director's version of Shakespeare's King Lear, set in medieval Japan (and the only film of Kurosawa's career that he received a "Best Director" Academy Award nomination for). It was by far the largest project of Kurosawa's late career, and he spent a decade planning it and trying to obtain funding, which he was finally able to do with the help of the French producer Serge Silberman. The film was an international success and is generally considered Kurosawa's last masterpiece. In an interview, Kurosawa said that he considered it to be the best film he ever made.

Kurosawa made three more films during the 1990s which were more personal than his earlier works. Dreams (1990) is a series of vignettes based on his own dreams. Rhapsody in August (1991) is about memories of the Nagasaki atomic bomb and his final film, Madadayo (1993), is about a retired teacher and his former students. Kurosawa died of a stroke in Setagaya, Tokyo, at age 88.[56]

After the Rain is a 1998 posthumous film directed by Kurosawa's closest collaborator, Takashi Koizumi, co-produced by Kurosawa Production (Hisao Kurosawa) and starring Tatsuya Nakadai and Shiro Mifune, son of Toshirō Mifune. The film's screenplay was written by Kurosawa. The story is based on a short novel by Shugoro Yamamoto, Ame Agaru.

To coincide with the 100th anniversary of Kurosawa's birth, his unfinished documentary Gendai no Noh will be completed and released in 2010. While filming his masterpiece Ran in 1983, Kurosawa experienced a number of problems during production, including financial troubles, and temporarily postponed filming to work on a non-fiction project. The documentary was to be about classic Japanese Noh theater, whose style had a substantial influence on Ran, as well as Throne of Blood and Kagemusha. Only about 50 minutes of footage exist, but to finish the film, an additional hour will be shot using Kurosawa's original screenplay.[57]

Legacy The Akira Kurosawa Foundation was established in December 2003.[58]

In commemoration of the 100th anniversary of Kurosawa's birth, the AK100 Project was created. The AK100 Project aims to "expose young people who are the representatives of the next generation, and all people everywhere, to the light and spirit of Akira Kurosawa and the wonderful world he created."[59]

Anaheim University launched the Anaheim University Akira Kurosawa School of Film at the Beverly Hills Hotel on March 23, 2009, which would have been Kurosawa's 99th birthday. Kurosawa's son, Hisao Kurosawa, attended as Guest of Honor and a special memorial tribute video was played at the event featuring video presentations from Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Martin Scorsese, Kurosawa's Assistant Director Teruyo Nogami and "Dreams" Producer/Nephew of Akira Kurosawa, Mike Inoue.[60]

Two awards have been named in Kurosawa's honor, the Akira Kurosawa Award for Lifetime Achievement in Film Directing, awarded during the San Francisco International Film Festival, and the Akira Kurosawa Award, awarded during the Tokyo International Film Festival.[61]

Filmography

Year Title Japanese Romanization

1943 Sanshiro Sugata

aka Judo Saga 姿三四郎 Sugata Sanshirō

1944 The Most Beautiful 一番美しく Ichiban utsukushiku

1945 Sanshiro Sugata Part II

aka Judo Saga 2 續姿三四郎 Zoku Sugata Sanshirô

The Men Who Tread on the Tiger's Tail 虎の尾を踏む男達 Tora no o wo fumu otokotachi

1946 No Regrets for Our Youth わが青春に悔なし Waga seishun ni kuinashi

1947 One Wonderful Sunday 素晴らしき日曜日 Subarashiki nichiyōbi

1948 Drunken Angel 酔いどれ天使 Yoidore tenshi

1949 The Quiet Duel 静かなる決闘 Shizukanaru ketto

Stray Dog 野良犬 Nora inu

1950 Scandal 醜聞 Sukyandaru

aka Shūbun

Rashomon 羅生門 Rashōmon

1951 The Idiot 白痴 Hakuchi

1952 Ikiru

aka To Live 生きる Ikiru

1954 Seven Samurai 七人の侍 Shichinin no samurai

1955 I Live in Fear

aka Record of a Living Being 生きものの記録 Ikimono no kiroku

1957 Throne of Blood

aka Spider Web Castle 蜘蛛巣城 Kumonosu-jō

The Lower Depths どん底 Donzoko

1958 The Hidden Fortress 隠し砦の三悪人 Kakushi toride no san akunin

1960 The Bad Sleep Well 悪い奴ほどよく眠る Warui yatsu hodo yoku nemuru

1961 Yojimbo

aka The Bodyguard 用心棒 Yōjinbō

1962 Sanjuro 椿三十郎 Tsubaki Sanjūrō

1963 High and Low

aka Heaven and Hell 天国と地獄 Tengoku to jigoku

1965 Red Beard 赤ひげ Akahige

1970 Dodesukaden* どですかでん Dodesukaden

1975 Dersu Uzala デルス・ウザーラ Derusu Uzāra

1980 Kagemusha

aka The Shadow Warrior 影武者 Kagemusha

1985 Ran 乱 Ran

1990 Dreams

aka Akira Kurosawa's Dreams 夢 Yume

1991 Rhapsody in August 八月の狂詩曲 Hachigatsu no rapusodī

aka Hachigatsu no kyōshikyoku

1993 Madadayo

aka Not Yet まあだだよ Mādadayo

*日本語

Dodes'ka-den (どですかでん Dodesukaden?, literally, "Clickety-clack") is a 1970 Japanese film directed by Akira Kurosawa and based on the Shūgorō Yamamoto[1] bookKisetsu no nai machi ("The Town Without Seasons").

羅斌

どですかでん Dodesukaden

Masterpiece by Kurosawa. The movie was a critical success, but a commercial failure, which sent Kurosawa into a deep depression, and in 1971 he attempted suicide. Despite having slashed himself over 30 times with a razor, Kurosawa survived.

Dodes'ka-den

Dodes'ka-den - Roku-chan's make-believe trolley

Akira Kurosawa, 1970. Music by Tôru Takemitsu.

YOUTU.BE

獲獎使電影在日本重被重視,電視也予以播放。在電視播出時,電視台訪問了原製作公司的社長,這個社長得意洋洋地說,是他自己一手推動這部作品的。黑澤看了說不出話來。因為當初拍這部片時,社長明明面有難色,說這是甚麼讓人看不下去的東西,而且把推動這部作品的高層和製片降職。社長還滔滔不絕地重複外國影評誇獎這部片的攝影技術,說這部片第一次把攝影機面對太陽拍攝。而直到採訪最後,他都沒有提到黑澤明和攝影師宮本的名字。

黑澤看了這段訪問,覺得簡直就是《羅生門》啊。 電影《羅生門》本身,固然表現了可悲的人性,而在獲獎及在電視播出時,也呈現出同樣的人性。

他再次知道,人有本能地美化自己的天性,人很難如實地談論自己。可是,黑澤說,他不能嘲笑這位社長。他反省說:「我寫這本自傳,裏面真的都老老實實寫我自己嗎?是否沒有觸及自己醜陋的部分?是否或大或小美化了自己?寫到《羅生門》無法不反省。於是筆尖無法繼續前進。《羅生門》雖然把我以電影人的身份送出世界之門,但寫了自傳的我,無法從那扇門再往前寫。」

黑澤明以真誠的心,奉獻了芥川龍之介的人性之作,而創作《羅生門》的過程和結果,也創造了黑澤明自己。在創造了許多被世界肯定的傑作之後,仍然能夠如此真誠地反省自己。我們終於知道黑澤明之所以偉大的原因了,就是他有與眾不同的內在反省能力。是不是每個人都無法擺脫這種不能如實談論自己的虛飾的人性呢?常說要忠於自己的人,包括我在內,真要好好想一想。

The Sea Is Watching Buy this Movie

Madadayo Buy this Movie

Rhapsody in August Buy this Movie

Akira Kurosawa's Dreams Buy this Movie

Ran Buy this Movie

Kagemusha Buy this Movie

Dersu Uzala

Akira Kurosawa on set

Born 23 March 1910(1910-03-23)

Shinagawa, Tokyo, Japan

Died 6 September 1998 (aged 88)

Setagaya, Tokyo, Japan

Occupation film director, screenwriter, editor, film producer

Years active 1936–1993

Spouse(s) Yōko Yaguchi (1921–1985)

Youth Akira Kurosawa was born to Isamu and Shima Kurosawa on 23 March 1910.[2] He was the youngest of eight children born to the Kurosawas in a suburb of Tokyo.[3] Shima Kurosawa was 40 years old at the time of Akira's birth and his father Isamu was 45. Akira Kurosawa grew up in a household with three older brothers and four older sisters. Of his three older brothers, one died before Akira was born and one was already grown and out of the household. One of his four older sisters had also left the home to begin her own family before Kurosawa was born. Kurosawa's next-oldest sibling, a sister he called "Little Big Sister," also died suddenly after a short illness when he was 10 years old.

Kurosawa's father worked as the director of a junior high school operated by the Japanese military and the Kurosawas descended from a line of former samurai. Financially, the family was above average. Isamu Kurosawa embraced western culture both in the athletic programs that he directed and by taking the family to see films, which were then just beginning to appear in Japanese theaters. Later, when Japanese culture turned away from western films, Isamu Kurosawa continued to believe that films were a positive educational experience.

In primary school, Kurosawa was encouraged to draw by Tachikawa, a teacher who took an interest in mentoring his talents. Both Tachikawa and his brother Heigo had a profound impact on him.[3] Heigo was very intelligent and won several academic competitions but also had what was later called a cynical or dark side. In 1923, the Great Kantō earthquake destroyed Tokyo and left 100,000 people dead. In the wake of this event, Heigo, 17, and Akira, 13, made a walking tour of the devastation. Corpses of humans and animals were piled everywhere. When Akira would attempt to turn his head away, Heigo urged him not to. According to Akira, this experience would later instruct him that to look at a frightening thing head-on is to defeat its ability to cause fear.[4]

Heigo eventually began a career as a benshi in Tokyo film theaters. Benshi narrated silent films for the audience and were a uniquely Japanese addition to the theater experience. In the transition to talking pictures, later in Japan than elsewhere, benshi lost work all over the country. Heigo organized a benshi strike that failed. Akira was likewise involved in labor-management struggles, writing several articles for a radical newspaper while improving and expanding his skills as a painter and reading literature.

When Akira Kurosawa was in his early 20s, his older brother Heigo committed suicide. Four months later, the oldest of Kurosawa's brothers also died, leaving Akira, at age 23, as the only surviving son of an original four.

Personal life Kurosawa's wife was actress Yoko Yaguchi.[5] He had two children with her: a son named Hisao (who became a producer and worked with his father on the films Ran, Dreams, Rhapsody in August, and Madadayo)[6] and a daughter named Kazuko.

Early career

His first post-war film No Regrets for Our Youth (1946), by contrast, is critical of the old Japanese regime and is about the wife of a left-wing dissident who is arrested for his political leanings. Kurosawa made several more films dealing with contemporary Japan, most notably Drunken Angel (1948) and Stray Dog (1949). However, it was the period film Rashomon (1950) which led to him being known internationally and won him the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival.[8]

Directorial approach Kurosawa had a distinctive cinematic technique, which he had developed by the 1950s. He liked using telephoto lenses for the way they flattened the frame. He believed that placing cameras farther away from his actors produced better performances as they would not be conscious of the camera. He also liked using multiple cameras, which allowed him to shoot an action scene from different angles. As with the use of telephoto lenses, the multiple-camera technique also prevented Kurosawa's actors from "figuring out which one is shooting him [and invariably turning] one-third to halfway in its direction."[9] Another Kurosawa trademark was the use of weather elements to heighten mood; for example, the heavy rain in the opening scene of Rashomon and the final battle in Seven Samurai (1954); the intense heat in Stray Dog; the cold wind in Yojimbo (1961); the snow in Ikiru (1952); and the fog in Throne of Blood (1957). Kurosawa also liked using frame wipes, sometimes cleverly hidden by motion within the frame, as a transition device.

He was known as "Tenno", literally "Emperor", for his dictatorial directing style. He was a perfectionist who spent enormous amounts of time and effort to achieve the desired visual effects. For the rainstorm scenes in Rashomon, because the falling water (provided by fire trucks) did not show up on film against the sky, he dyed the water black with calligraphy ink in order to achieve the effect of heavy rain.[10] In the final scene of Throne of Blood, in which Mifune is shot by arrows, Kurosawa used real arrows shot by expert archers from a short range, landing within centimetres of Mifune's body.[11] In Ran (1985), an entire castle set was constructed on the slopes of Mt. Fuji only to be burned to the ground in a climactic scene.[12]

Other stories include demanding a stream be made to run in the opposite direction in order to get a better visual effect, and having the roof of a house removed, later to be replaced, because he felt the roof's presence to be unattractive in a short sequence filmed from a train.

His perfectionism also showed in his approach to costumes: he felt that giving an actor a brand new costume made the character look less than authentic. To resolve this, he often gave his cast their costumes weeks before shooting was to begin and required them to wear them on a daily basis and "bond with them." In some cases, such as with Seven Samurai, where most of the cast portrayed poor farmers, the actors were told to make sure the costumes were worn down and tattered by the time shooting started.

Kurosawa did not believe that "finished" music went well with film. When choosing a musical piece to accompany his scenes, he usually had it stripped down to one element (e.g., trumpets only). Only towards the end of his films are more finished pieces heard.

Unusual among directors, Kurosawa edited his films himself during production. After each day's shooting he would go to the cutting room and cut the dailies.[11]

Influences A notable feature of Kurosawa's films is the breadth of his artistic influences. Some of his plots are based on William Shakespeare's works: Ran is loosely based on King Lear, Throne of Blood is based on Macbeth, while The Bad Sleep Well (1960) parallels Hamlet, but is not affirmed to be based on it. Kurosawa also directed film adaptations of Russian literary works, including The Idiot (1951) by Dostoevsky (his favorite author) and The Lower Depths (1957), from the play by Maxim Gorky. Ikiru was inspired by Leo Tolstoy's The Death of Ivan Ilyich. Dersu Uzala (1975) was based on the 1923 memoir of the same title by Russian explorer Vladimir Arsenyev. Story lines in Red Beard (1965) can be found in The Insulted and Humiliated by Dostoevsky.

High and Low (1963) was based on King's Ransom by American crime writer Ed McBain. Yojimbo may have been based on Dashiell Hammett's Red Harvest and also borrows from American Westerns. Kurosawa was very fond of Georges Simenon and Stray Dog was a product of Kurosawa's desire to make a film in Simenon's manner.[13]

Cinematic influences include Frank Capra, William Wyler, Howard Hawks, his mentor Kajiro Yamamoto, and his favorite director John Ford,[14] whose habit of wearing dark glasses Kurosawa emulated. When Kurosawa met Ford, the American simply said, "You really like rain." Kurosawa responded, "You've really been paying attention to my films."[15] He would later instruct Yoshio Tsuchiya, one of the actors in Seven Samurai, to retrieve the same hat Ford wore during that meeting.[16]

Despite criticism by some Japanese critics that Kurosawa was "too Western,"[17] he was deeply influenced by Japanese culture as well, such as the Noh theaters and the Jidaigeki (period drama) genre of Japanese cinema.

Influence Seven Samurai was remade as The Magnificent Seven (1960)[18]. Seven Samurai is also considered the progenitor of the "men on a mission" film, popularized by films such as The Dirty Dozen (1967) and The Guns of Navarone (1961). The film is also recognized for popularizing the use of slow-motion in action films/sequences.

Rashomon was remade by Martin Ritt in 1964's The Outrage. Several films and television programs have also come to use what is known as the Rashomon effect, wherein various people give opposing or contrasting accounts of an event; these films include, but are not limited to Vantage Point, Courage Under Fire, Hero, Hoodwinked, and The Usual Suspects. Tajomaru, a film that centers on the eponymous character from Rashomon, was released in 2009.

Yojimbo was unofficially remade as the Sergio Leone western A Fistful of Dollars (1964) (resulting in a successful lawsuit by Kurosawa)[19] and was remade as the prohibition-era film Last Man Standing (1996). Sanjuro was remade in 2007 as Tsubaki Sanjuro, directed by Yoshimitsu Morita.

The Hidden Fortress (1957) was remade as The Last Princess (2008) and is an acknowledged influence on George Lucas's Star Wars films, in particular Episodes IV and VI and most notably in the characters of R2-D2 and C-3PO.[20][21] As well as using a modified version of Kurosawa's signature wipe transition, it has been observed that specific scenes from various Kurosawa films have been emulated throughout George Lucas's Star Wars saga.[21]

Remakes for Ikiru[22] and High and Low[23] are in progress. Second remakes for Rashomon and Seven Samurai are also on the way.[24][25]

The following directors either were directly influenced by Kurosawa, or greatly admired his work:

Satyajit Ray[citation needed] - the great Indian director (famous for his Apu trilogy) and winner of Oscar Lifetime Achievement award.

Andrei Tarkovsky[26][27]

Ingmar Bergman[28] - "Now I want to make it plain that The Virgin Spring must be regarded as an aberration. It's touristic, a lousy imitation of Kurosawa."[29]

Federico Fellini[30] - Having only seen Seven Samurai from Kurosawa's oeuvre, he still thought Kurosawa was the "the greatest living example of what an author of the cinema should be."[31]

Bernardo Bertolucci - "Kurosawa's movies and La Dolce Vita, Fellini, are the things that pushed me sucked into being a film director."[32]

Robert Altman[33][34]

Sidney Lumet - "Kurosawa never affected me directly in terms of my own movie-making because I never would have presumed that I was capable of that perception and that vision."[35]

Sam Peckinpah - "I'd like to be able to make a Western like Kurosawa makes Westerns."[36]

Roman Polanski[37]

Steven Spielberg[38] - "the pictorial Shakespeare of our time"[39]

Martin Scorsese[38] - "His influence on filmmakers throughout the entire world is so profound as to be almost incomparable."[39]

George Lucas[21][38]

Francis Ford Coppola[40] - "One thing that distinguishes Akira Kurosawa is that he didn't make a masterpiece or two masterpieces, he made, you know, eight masterpieces."[41]

Zhang Yimou - "Other filmmakers have more money, more advanced techniques, more special effects. Yet no one has surpassed him."[42]

John Milius[43]

Takeshi Kitano - "...the ideal definition of cinema: a succession of perfect images. And Kurosawa is the only director who has attained that."[44]

John Woo[45][46] - "I love Kurosawa’s movies, and I got so much inspiration from him. He is one of my idols and one of the great masters"[47]

Werner Herzog[48] - "Of the filmmakers with whom I feel some kinship Griffith, Murnau, Pudovkin, Buñuel and Kurosawa come to mind. Everything these men did has the touch of greatness."[49]

Antoine Fuqua[50]

Alex Cox[51]

Arthur Penn[52][53]

Spike Lee[citation needed]

Sergio Leone

Collaboration During his most productive period, from the late 40s to the mid-60s, Kurosawa often worked with the same group of collaborators. Fumio Hayasaka composed music for seven of his films — notably Rashomon, Ikiru and Seven Samurai. When Hayasaka died, he collaborated with composer Masaru Satō, who scored most of his later films. Kurosawa worked with the same five scriptwriters during his career: Eijiro Hisaita, Ryuzo Kikushima, Shinobu Hashimoto, Hideo Oguni, and Masato Ide.[54] Yoshiro Muraki was Kurosawa's production designer or art director for most of his films after Stray Dog in 1949, and Asakazu Nakai was his cinematographer on 11 films including Ikiru, Seven Samurai and Ran. Kurosawa also liked working with the same group of actors, especially Takashi Shimura, Tatsuya Nakadai, and Toshirō Mifune. His collaboration with the latter, which began with 1948's Drunken Angel and ended with 1965's Red Beard, is one of the most famous director-actor collaborations in cinema history.

Later films The film Red Beard marked a turning point in Kurosawa's career in more ways than one. In addition to being his last film with Mifune, it was his last in black-and-white. It was also his last as a major director within the Japanese studio system making roughly a film a year. Kurosawa was signed to direct a Hollywood project, Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970) but 20th Century Fox replaced him with Toshio Masuda and Kinji Fukasaku before it was completed.[55] His next few films were to be significantly more difficult to finance and were made at intervals of five years. The first, Dodesukaden (1970), about a group of poor people living around a rubbish dump, was not a commercial or financial success.

After an attempted suicide, Kurosawa went on to make several more films, although he had great difficulty in obtaining domestic financing despite his international reputation. Dersu Uzala, made in the Soviet Union and set in Siberia in the early 20th century, was the only Kurosawa film made outside of Japan and not in the Japanese language. It is about the friendship of a Russian explorer and a nomadic hunter, and won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. Kagemusha (1980), financed with the help of the director's most famous admirers, George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola, is the story of a man who is the body double of a medieval Japanese lord and takes over his identity after the lord's death. The film was awarded the Palme d'Or (Golden Palm) at the 1980 Cannes Film Festival (shared with Bob Fosse's All That Jazz). Ran was the director's version of Shakespeare's King Lear, set in medieval Japan (and the only film of Kurosawa's career that he received a "Best Director" Academy Award nomination for). It was by far the largest project of Kurosawa's late career, and he spent a decade planning it and trying to obtain funding, which he was finally able to do with the help of the French producer Serge Silberman. The film was an international success and is generally considered Kurosawa's last masterpiece. In an interview, Kurosawa said that he considered it to be the best film he ever made.

Kurosawa made three more films during the 1990s which were more personal than his earlier works. Dreams (1990) is a series of vignettes based on his own dreams. Rhapsody in August (1991) is about memories of the Nagasaki atomic bomb and his final film, Madadayo (1993), is about a retired teacher and his former students. Kurosawa died of a stroke in Setagaya, Tokyo, at age 88.[56]

After the Rain is a 1998 posthumous film directed by Kurosawa's closest collaborator, Takashi Koizumi, co-produced by Kurosawa Production (Hisao Kurosawa) and starring Tatsuya Nakadai and Shiro Mifune, son of Toshirō Mifune. The film's screenplay was written by Kurosawa. The story is based on a short novel by Shugoro Yamamoto, Ame Agaru.

To coincide with the 100th anniversary of Kurosawa's birth, his unfinished documentary Gendai no Noh will be completed and released in 2010. While filming his masterpiece Ran in 1983, Kurosawa experienced a number of problems during production, including financial troubles, and temporarily postponed filming to work on a non-fiction project. The documentary was to be about classic Japanese Noh theater, whose style had a substantial influence on Ran, as well as Throne of Blood and Kagemusha. Only about 50 minutes of footage exist, but to finish the film, an additional hour will be shot using Kurosawa's original screenplay.[57]

Legacy The Akira Kurosawa Foundation was established in December 2003.[58]

In commemoration of the 100th anniversary of Kurosawa's birth, the AK100 Project was created. The AK100 Project aims to "expose young people who are the representatives of the next generation, and all people everywhere, to the light and spirit of Akira Kurosawa and the wonderful world he created."[59]

Anaheim University launched the Anaheim University Akira Kurosawa School of Film at the Beverly Hills Hotel on March 23, 2009, which would have been Kurosawa's 99th birthday. Kurosawa's son, Hisao Kurosawa, attended as Guest of Honor and a special memorial tribute video was played at the event featuring video presentations from Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Martin Scorsese, Kurosawa's Assistant Director Teruyo Nogami and "Dreams" Producer/Nephew of Akira Kurosawa, Mike Inoue.[60]

Two awards have been named in Kurosawa's honor, the Akira Kurosawa Award for Lifetime Achievement in Film Directing, awarded during the San Francisco International Film Festival, and the Akira Kurosawa Award, awarded during the Tokyo International Film Festival.[61]

Filmography

Year Title Japanese Romanization

1943 Sanshiro Sugata

aka Judo Saga 姿三四郎 Sugata Sanshirō

1944 The Most Beautiful 一番美しく Ichiban utsukushiku

1945 Sanshiro Sugata Part II

aka Judo Saga 2 續姿三四郎 Zoku Sugata Sanshirô

The Men Who Tread on the Tiger's Tail 虎の尾を踏む男達 Tora no o wo fumu otokotachi

1946 No Regrets for Our Youth わが青春に悔なし Waga seishun ni kuinashi

1947 One Wonderful Sunday 素晴らしき日曜日 Subarashiki nichiyōbi

1948 Drunken Angel 酔いどれ天使 Yoidore tenshi

1949 The Quiet Duel 静かなる決闘 Shizukanaru ketto

Stray Dog 野良犬 Nora inu

1950 Scandal 醜聞 Sukyandaru

aka Shūbun

Rashomon 羅生門 Rashōmon

1951 The Idiot 白痴 Hakuchi

1952 Ikiru

aka To Live 生きる Ikiru

1954 Seven Samurai 七人の侍 Shichinin no samurai

1955 I Live in Fear

aka Record of a Living Being 生きものの記録 Ikimono no kiroku

1957 Throne of Blood

aka Spider Web Castle 蜘蛛巣城 Kumonosu-jō

The Lower Depths どん底 Donzoko

1958 The Hidden Fortress 隠し砦の三悪人 Kakushi toride no san akunin

1960 The Bad Sleep Well 悪い奴ほどよく眠る Warui yatsu hodo yoku nemuru

1961 Yojimbo

aka The Bodyguard 用心棒 Yōjinbō

1962 Sanjuro 椿三十郎 Tsubaki Sanjūrō

1963 High and Low

aka Heaven and Hell 天国と地獄 Tengoku to jigoku

1965 Red Beard 赤ひげ Akahige

1970 Dodesukaden* どですかでん Dodesukaden

1975 Dersu Uzala デルス・ウザーラ Derusu Uzāra

1980 Kagemusha

aka The Shadow Warrior 影武者 Kagemusha

1985 Ran 乱 Ran

1990 Dreams

aka Akira Kurosawa's Dreams 夢 Yume

1991 Rhapsody in August 八月の狂詩曲 Hachigatsu no rapusodī

aka Hachigatsu no kyōshikyoku

1993 Madadayo

aka Not Yet まあだだよ Mādadayo

*日本語

Dodes'ka-den (どですかでん Dodesukaden?, literally, "Clickety-clack") is a 1970 Japanese film directed by Akira Kurosawa and based on the Shūgorō Yamamoto[1] bookKisetsu no nai machi ("The Town Without Seasons").

羅斌

どですかでん Dodesukaden

Masterpiece by Kurosawa. The movie was a critical success, but a commercial failure, which sent Kurosawa into a deep depression, and in 1971 he attempted suicide. Despite having slashed himself over 30 times with a razor, Kurosawa survived.

Dodes'ka-den

Dodes'ka-den - Roku-chan's make-believe trolley

Akira Kurosawa, 1970. Music by Tôru Takemitsu.

YOUTU.BE

Home video release

Unlike his other noted contemporaries, such as Yasujiro Ozu or Kenji Mizoguchi, the majority of Kurosawa's work is commercially available throughout the U.S. and Europe.The Criterion Collection is the primary distributor of Kurosawa's films on DVD in the U.S., issuing 16 of his films as individual DVDs, with frequent contributions from Kurosawa historians Stephen Price and Donald Richie, and a further 5 issued in the "Post-War Kurosawa" Boxset as part of the label's Eclipse brand. Combined, these cover all the directors films from 1946's No Regrets for Our Youth to 1985's Ran except 1949's The Quiet Duel and 1975's Dersu Uzala. Kurosawa's first four films, Sanshiro Sugata, The Most Beautiful, Sanshiro Sugata Part II and The Men Who Tread on the Tiger's Tail, never previously available on DVD, are included with Criterion's other Kurosawa releases in the AK 100: 25 Films by Akira Kurosawa Boxset released to mark the 100th anniversary of the director's birth on December 8, 2009.[62] The director's remaining work, The Quiet Duel, Dersu Uzala, Dreams, Rhapsody in August and Madadayo, have all been commercially available on DVD in the U.S., though some are currently out of print. The first Kurosawa film to be released in the U.S. on Blu-ray was Kagemusha in August 2009.

See also

Notes

- ^ "Akira Kurosawa - AKIRA KUROSAWA DRAWINGS". Kurosawa-drawings.com. http://www.kurosawa-drawings.com/page/8. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ "Akira Kurosawa: Biography". Bfi.org.uk. 2007-08-31. http://www.bfi.org.uk/features/kurosawa/biography.html. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ a b Richie, Donald (1999). The Films of Akira Kurosawa. University of California Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 0520220374.

- ^ Kurosawa, Akira (1983). Something Like An Autobiography. Vintage Books. pp. 53–54. ISBN 0394714393.

- ^ Kurosawa, Akira (1983). Something Like An Autobiography. Vintage Books. p. 134. ISBN 0394714393.

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0475902/

- ^ "Akira Kurosawa (1910–1998)". Kirjasto.sci.fi. http://www.kirjasto.sci.fi/kuros.htm. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ "Akira Kurosawa - Awards". Imdb.com. http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0000041/awards. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ Kurosawa, Akira (1983). Something Like An Autobiography. Vintage Books. pp. 195. ISBN 0394714393.

- ^ Kurosawa, Akira (1983). Something Like An Autobiography. Vintage Books. p. 185. ISBN 0394714393.

- ^ a b Galbraith IV, Stuart (2002). The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune. Faber & Faber. p. 235. ISBN 0571199828.

- ^ Nogami, Teruyo (2006). Waiting on the Weather: Making Movies with Akira Kurosawa. Stone Bridge Press. pp. 115–117. ISBN 0571199828.

- ^ Richie, Donald (1999). The Films of Akira Kurosawa. University of California Press. p. 58. ISBN 0520220374.

- ^ Richie, Donald (1999). The Films of Akira Kurosawa. University of California Press. pp. 45, 242. ISBN 0520220374.

- ^ Chris Marker (Director). (1985). A.K.. Criterion Collection.

- ^ Yoshio Tsuchiya (speaker). (1999). Kurosawa: The Last Emperor.

- ^ Galbraith IV, Stuart (2002). The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune. Faber & Faber. p. 119. ISBN 0571199828.

- ^ Erickson, Hal. "The Magnificent Seven > Overview". AllMovie. http://www.allmovie.com/work/the-magnificent-seven-30854. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ "American Museum of the Moving Image - Yojimbo". Movingimage.us. http://www.movingimage.us/film_programs/program_notes/y/yojimbo.html. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ Introduction to Criterion Collection DVD release of The Hidden Fortress.

- ^ a b c "The Secret History of Star Wars". The Secret History of Star Wars. http://secrethistoryofstarwars.com/kurosawa1.html. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ By. "Irish eyes smile on DreamWorks' 'Ikiru' remake". Variety.com. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117910213.html?categoryid=1236&cs=1. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ "Nichols Directing High and Low Remake". Comingsoon.net. http://www.comingsoon.net/news/movienews.php?id=50083. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ By. "'Rashomon' remake finds a Harbor". Variety.com. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117992608.html?categoryid=13&cs=1. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ "The Seven Samurai (2009) IMDb entry". Imdb.com. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0814315/. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ "Tarkovsky's Choice". Acs.ucalgary.ca. http://www.acs.ucalgary.ca/~tstronds/nostalghia.com/TheTopics/Tarkovsky-TopTen.html. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ Gianvito, John; Andrei Tarkovsky (2006). Andrei Tarkovsky: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi. p. 30. ISBN 1578062209.

- ^ Ingmar Bergman Foundation. "Bergman's list". Ingmarbergman.se. http://www.ingmarbergman.se/universe.asp?guid=576B4E1D-0B33-490D-985C-FC4627FAF3B8. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ Ingmar Bergman Foundation. "Ingmar Bergman on Akira Kurosawa". Ingmarbergman.se. http://www.ingmarbergman.se/universe.asp?guid=2E2291EF-1288-4A78-9510-B00F0F1D4CDB. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ INTERVIEW BY TONI MARAINI Translated by A. K. Bierman. "An Interview with Federico Fellini". Brightlightsfilm.com. http://www.brightlightsfilm.com/26/fellini1.html. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ Cardullo, Bert; Federico Fellini (2006). Federico Fellini: Interviews. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 49. ISBN 1578068851.

- ^ Bernardo Bertolucci (speaker). (1999). Kurosawa: The Last Emperor.

- ^ "Master of reinvention". Smh.com.au. http://www.smh.com.au/news/film/master-of-reinvention/2006/09/28/1159337269904.html?page=3. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ Phipps, Keith. "Robert Altman". A.V. Club. http://www.avclub.com/articles/robert-altman,13670/. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ Introduction to Criterion Collection DVD release of Ran

- ^ Hayes, Kevin J. (2008). Sam Peckinpah: Interviews. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 15. ISBN 1934110647.

- ^ Morrison, James (2007). Roman Polanski. University of Illinois Press. p. 160. ISBN 0252074467.

- ^ a b c "Akira Kurosowa Memorial Tribute". Anaheim.edu. http://www.anaheim.edu/content/view/758/720/. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ a b "Eugene Register-Guard - Google News Archive Search". 1998-09-07. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=8ncVAAAAIBAJ&sjid=t-sDAAAAIBAJ&pg=5882%2C1850102. Retrieved 2010-01-01.

- ^ "The Hollywood Interview: FRANCIS COPPOLA INTERVIEW!". Thehollywoodinterview.blogspot.com. 2008-01-07. http://thehollywoodinterview.blogspot.com/2007/12/francis-coppola-goes-back-to-basics-by.html. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ Francis Ford Coppola (speaker). (1999). Kurosawa: The Last Emperor.

- ^ "Time 100: Akira Kurosawa". Time.com. 1910-03-23. http://www.time.com/time/asia/asia/magazine/1999/990823/kurosawa1.html. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ by Ken P. (1944-04-11). "IGN: An Interview with John Milius". Movies.ign.com. http://movies.ign.com/articles/401/401150p7.html. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ Tirard, Laurent (2002). Moviemakers' Master Class: Private Lessons from the World's Foremost Directors. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 167. ISBN 057121102X.

- ^ John Woo (speaker). (1999). Kurosawa: The Last Emperor.

- ^ Interview by Nev Pierce (2004-01-16). "Movies - Calling the Shots No.10: John Woo". BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/films/callingtheshots/john_woo.shtml. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ "Epic homecoming". Star-ecentral.com. 2008-07-15. http://www.star-ecentral.com/news/story.asp?file=/2008/7/15/movies/20080714201452&sec=movies. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ "The secret mainstream: Contemplating the mirages of Werner Herzog". Harpers.org. http://www.harpers.org/archive/2006/12/0081313. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ Cronin, Paul; Werner Herzog (2003). Herzog on Herzog. Faber & Faber. p. 138. ISBN 0571207081.

- ^ Interview by Adrian Hennigan. "Movies - Calling the Shots No.18: Antoine Fuqua". BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/films/callingtheshots/antoine_fuqua.shtml. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ "Kurosawa - The Last Emperor". Alexcox.com. http://www.alexcox.com/dir_lastemperor.htm. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ "The Hollywood Interview: Arthur Penn". Thehollywoodinterview.blogspot.com. 2009-04-09. http://thehollywoodinterview.blogspot.com/2009/04/arthur-penn-hollywood-interview.html. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ D. Friedman, Lester (1999). Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde. Cambridge University Press. p. 138. ISBN 0521596971.

- ^ Richie, Donald (1999). The Films of Akira Kurosawa. University of California Press. p. 230. ISBN 0520220374.

- ^ Walter Chaw (2001-06-20). "TORA! TORA! TORA - Film Fream Central". Filmfreakcentral.net. http://www.filmfreakcentral.net/dvdreviews/toratoratora.htm. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ "Filmmaker Akira Kurosawa Dies at 88; Japanese Director Acclaimed Worldwide - The Washington Post". Encyclopedia.com. 1998-09-07. http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1P2-669984.html. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ "Unfinished footage by Kurosawa to be released". Akirakurosawa.info. 2008-03-02. http://akirakurosawa.info/2008/03/02/unfinished-footage-by-kurosawa-to-be-released/. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ "Welcome to Akira Kurosawa Foundation". Kurosawa-foundation.com. http://www.kurosawa-foundation.com/eng/index.html. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ "AK100 Project" (in (Japanese)). Akirakurosawa100.com. http://akirakurosawa100.com/. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ "Anaheim University Akira Kurosawa Memorial Tribute". Anaheim.edu. http://www.anaheim.edu/content/view/748/718/. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ "Tokyo International Film Festival | Prizes". Tiff-jp.net. http://www.tiff-jp.net/en/awards/. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ^ "AK 100: 25 Films by Akira Kurosawa". CriterionCo. http://www.criterion.com/boxsets/678. Retrieved December 9, 2009.

References

- Galbraith IV, Stuart (2002). The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune. Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-19982-8

- Richie, Donald; Mellen, Joan (1999). The Films of Akira Kurosawa. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22037-4

- Kurosawa, Akira (1983). Something Like An Autobiography. Vintage Books USA. ISBN 0-394-71439-3

- Nogami, Teruyo (2006). Waiting on the Weather: Making Movies With Akira Kurosawa. Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 1-933-33009-0

- Akira Kurosawa: Biography

- Akira Kurosawa (1910–1998)

Further reading

- Buchanan, Judith (2005). Shakespeare on Film. Longman-Pearson. Chapter 3. ISBN 0582437164

- Cardullo, Bert (2007). Akira Kurosawa: Interviews (Conversations with Filmmakers). University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1-578-06997-1

- Goodwin, James (1993). Akira Kurosawa and Intertextual Cinema. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-801-84661-7

- Goodwin, James (1994). Perspectives on Akira Kurosawa. G.K. Hall & Co.. ISBN 0-816-11993-7

- Martinez, Dolores (2009). Remaking Kurosawa: Translations and Permutations in Global Cinema. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0312293585

- Prince, Stephen (1999). The Warrior's Camera. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01046-3

- Yoshimoto, Mitsuhiro (2000). Kurosawa: Film Studies and Japanese Cinema. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-2519-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Akira Kurosawa |

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Akira Kurosawa |

- Akira Kurosawa at the Internet Movie Database

- Akira Kurosawa at the TCM Movie Database

- Akira Kurosawa News and Information

- Senses of Cinema: Great Directors Critical Database

- Great Performances: Kurosawa (PBS)

- Pacific Film Archive

- Akira Kurosawa Foundation

- (Japanese) Akira Kurosawa portalsite

- (Japanese) Akira Kurosawa Digital Archive

- (Japanese) Akira Kurosawa at Japanese celebrity's grave guide

- Akira Kurosawa (Japanese) at the Japanese Movie Database

沒有留言:

張貼留言