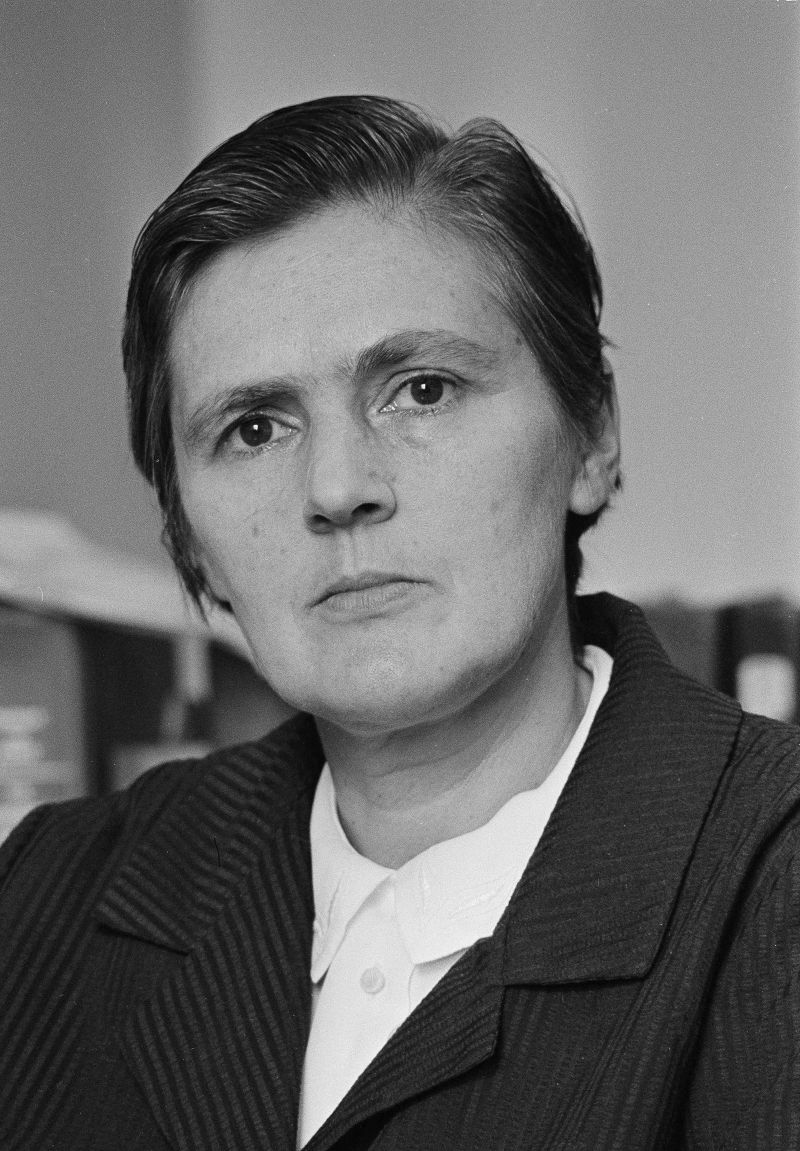

Dr. Frances Oldham Kelsey, who became famous for withholding Food and Drug Administration approval for Thalidomide in the early 1960s, died last week at 101. Notice of her death has been accompanied by retellings of the FDA’s early days, and of Kelsey’s heroic stand against the morning sickness drug later linked to terrible birth defects in other parts of the world. Rather than merely a story of one dogged researcher’s triumph, though, sociologist Monica Prasad sees the Thalidomide case as clear evidence against the notion of a laissez-faire United States government. Indeed, in The Land of Too Much: American Abundance and the Paradox of Poverty, excerpted below, Prasad offers the episode as an entry point for considering the weak U.S. welfare state as the product not of an unbridled free market but of a unique and remarkable system of American regulatory institutions.

-----

Doctors began to notice the first cases of the strange disease in 1959. Thousands of babies with stunted limbs and other severe birth defects were being born all over Germany, Britain, Sweden, Australia, dozens of countries. Many died from their deformities at birth. Others would experience difficulties as they grew, including heart disease and spina bifida. Through 1960 and into 1961, all around the world, the number of cases mounted.

In 1961 two doctors traced the problems to a sedative called Contergan that had been developed in Germany and marketed worldwide under other names. Contergan was prescribed for insomnia and for nausea. It did not seem to have side effects and was not toxic in overdose, and it became so popular that it was called “West Germany’s baby sitter.” But as the incidents rose, pediatricians began to suspect and then to document an extremely strong association between the birth defects and Contergan taken in the first trimester of pregnancy. It was withdrawn from the market in 1961, and eventually conclusive evidence emerged of how the drug caused the malformations. By then it had already affected over 10,000 children in “one of the greatest medical disasters of modern times.”1

Amid the calamity, a stunning and justly celebrated act of resistance came to light: under the name Thalidomide, the drug had been kept off the American market by Frances Kelsey, a researcher at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) with a hunch and a streak of self-confidence that led her to delay approval again and again, until the truth was finally known. Kelsey was well prepared for the task. She had done her graduate work in pharmacology at the University of Chicago (she was admitted on the assumption that “Frances” was a male name) in the lab that had identified the toxicity of an over-the-counter drug that had killed 107 people in 1937. The lab’s work led to the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938. During the war, Kelsey’s work on pregnant rabbits had shown her that drugs can cross the placental barrier and that pregnancy can change the body’s response to a drug.

The Thalidomide application was Kelsey’s first case at the FDA. Kelsey realized that the manufacturer’s and distributor’s studies documenting no adverse effects in animals were irrelevant because the drug also did not cause sleepiness in those experimental animals as it did in humans; it simply worked differently in humans. She called it “a peculiar drug.” Because the drug was aimed at relieving minor symptoms, she chose to wait for better evidence of its safety.

While there was no rush for Kelsey, there was a rush for the American distributor, Richardson-Merrell, which wanted approval in time for Christmas—Christmas apparently being the high season for sedatives—and sent representatives to make repeated visits and phone calls to Kelsey. As the months dragged on, nineteen months in all, the company complained to her superiors that Kelsey was being unreasonable. But she held her ground. Again and again the company resubmitted the application, arguing that any effects were so rare as to be negligible, and again and again Kelsey returned it for insufficient evidence of safety. Soon the European doctors had pieced together their conclusions, and Thalidomide stayed off the American market. Twenty cases of birth defects from suspected administrations of Thalidomide in the first trimester were documented in the United States, from travelers bringing the drug from Europe with them and from an early trial distribution of the drug. But the widespread tragedy that would have occurred had Kelsey been less persistent had been averted.

Historians of the episode have emphasized the role of Kelsey, and it is true that Kelsey’s ability to resist industry pressures requires the kind of explanation that cannot be reduced to social context and can really only be plumbed by close attention to the mysteries of human character. But there is one element in the story that does point to social context, and it does not reduce Frances Kelsey’s heroism to note the circumstances that allowed her resistance to be so powerful: the U.S. government has a long history of disapproving drugs available in other countries, a “drug lag” that has been the source of complaints from doctors as well as industry. This history of stronger drug regulation placed Kelsey in a position to disapprove Thalidomide. In Britain at the time, “any drug manufacturer could market any product, however inadequately tested, however dangerous, without having to satisfy any independent body as to its efficacy or safety”.2 Germany had a tradition of self-regulation by pharmacists and physicians. All that the government could do was recommend that a drug be removed from the market after the fact. In these countries there were no Frances Kelseys because there were no FDAs.

The divergent responses to the Thalidomide tragedy also demonstrate the tradition of stronger American drug regulation. Although Europe was more heavily hit, it was the United States that responded with tougher drug laws, so much so that by the 1970s, a widely reported study by physician William Wardell (1973) found that Great Britain had introduced four times as many drugs onto the market as the United States throughout the 1960s. A follow-up study by Wardell and Louis Lasagna (1975), head of Johns Hopkins’s Division of Clinical Pharmacology, found the United States lagging France, Great Britain, and Germany by one to two years in drug approvals. One particular drug for hypertension was introduced in Europe ten years before it was approved in the United States, and Wardell wondered how many deaths had been caused by that delay. In 1985, one study found that it took thirty months to approve a drug in the United States compared to six months in France and Britain; and other research showed that in Britain, 12% of drugs were found unsafe after having been introduced onto the market compared to only 3% in the United States, indicating a stricter preapproval process in the United States.

Although the drug-lag debate fed into a building deregulatory fervor, the issue of drug regulation did not allow for easy solutions. For example, one drug that Wardell had held up as an example of an important drug unnecessarily kept off the American market—Practolol—was later shown to have serious side effects and was eventually withdrawn from the market in Europe. Although the case did not receive much publicity, the FDA had once again been right where other countries had been wrong. While analysts tried to estimate and weigh the suffering caused in Europe by rushed approval, as in this case, against the suffering caused in the United States by delayed approval in other cases, the uncertainties ensured that the FDA would continue on its cautious path throughout the 1970s.

The story of Thalidomide has been interpreted from many different angles—as a tale about the predations of the drug industry, as a warning about the risks of unfettered scientific advance, as a parable of the difficulties of assessing risk in our complicated societies, as a way into the study of the social location of science. But the most surprising fact about it is that in this case it was the laissez-faire United States—the country that supposedly hates state intervention, the country allegedly most favorable to the market—that was the most successful at using the state to protect consumers from a pharmaceutical company wanting to market a dangerous drug, while the drug was welcomed all over statist Europe.

This is a surprise as all our theories of comparative political economy, in the disciplines of sociology, political science, and economics, insist that the United States is a liberal state with a strong tradition of minimal state intervention (using “liberal” here in the classical sense of an ideal of limited government). Within sociology, some analysts argue that national differences in political economy follow different cultural patterns, that the United States has a political culture that is “oriented to the reinforcement of market mechanisms to ensure economic liberties and effect growth, and the prevention of other forms of government meddling with economic life”

3 and that the United States “proclaims more than any other [economy] its conformity to the laissez-faire ideals that anchor the dominant streams of modern economic theory.”

4 Others argue that because of its weak labor movement and absence of a labor-backed political party, the United States has not been able to pass the policies that “modify conditions for and outcomes of market distribution.”

5 Within political science the dominant tradition of comparative political economy, the “varieties of capitalism” approach, sees the United States as a “liberal” regime in which “deregulation is often the most effective way to improve coordination,”

6 coordination problems are resolved through market-based rather than state-based solutions, and state intervention is used only to reinforce—not to undermine—market outcomes. The equally strong tradition of historical institutionalism argues that the American state has been unable to develop because of the multiple checks and balances in the political structure. Within economics, two prominent scholars have recently given the national culture argument a familiar twist, arguing that greater racial heterogeneity in the United States has led to persistent preferences for minimal state intervention because citizens believe that intervention will benefit those from other racial groups.

If the United States is so market oriented, so beholden to the weakness of labor, so liberal, and so suspicious of state intervention, where did that pattern of stricter drug regulation come from? Hundreds or thousands of Americans are walking around today with intact limbs and bodies because of the successful intervention of the American state against the market.

If drug regulation were the only policy to show this pattern, we would be justified in considering this story an absorbing trifle or in brushing it away with teleological arguments that consumer regulation preserves the market.

But in recent years, historically oriented scholars have shown that this example is not an exception—indeed, it seems to be the rule. William Novak summarizes this new generation of scholarship: “[T]he American state is and always has been more powerful, capacious, tenacious, interventionist, and redistributive than was recognized in earlier accounts of U.S. history” (2008, 758). So far, none of this nearly two decades’ worth of work has made it across the disciplinary divide to reorient comparative political economy. All of our theories of comparative political economy—with their implications for our understanding of economic growth and poverty reduction—have been built on a picture of American history that is turning out to be incorrect.

-----

1. Akhurst, Rosemary. 2010. “Taking Thalidomide Out of Rehab.” Nature Medicine 16(4): 370.

2. Ceccoli, Stephen. 2002. “Divergent Paths to Drug Regulation in the United States and the United Kingdom.” Journal of Policy History 14(2): 139.

3. Dobbin, Frank R. 1994. Forging Industrial Policy: The United States, Britain, and France in the Railway Age. New York: Cambridge University Press: 24.

4. Fouracde, Marion. 2009. Economists and Societies: Discipline and Profession in the United States, Britain, and France, 1890s to 1990s. Princeton: Princeton University Press: 254.

5. Korpi, Walter. 1983. The Democratic Class Struggle. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul: 173.

6. Hall, Peter A., and David W. Soskice. 2001. Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. New York: Oxford University Press: 9.

沒有留言:

張貼留言