The New York Review of Books

Adam Thirlwell on László Krasznahorkai, “one of the great inventors of new forms in contemporary literature” and winner of the 2015 Man Booker International Prize

Everything you need to know about László Krasznahorkai, winner of the Man Booker International prize

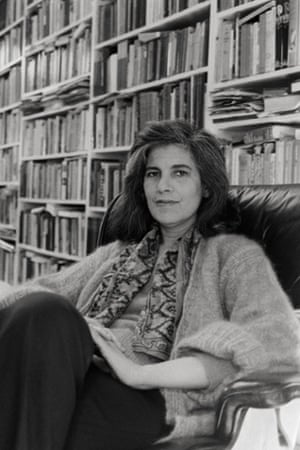

Little known in the English-speaking world, the Hungarian author has been praised by Susan Sontag and WG Sebald and his fans include a film director whose life’s mission is to bring his novels to the screen

Awards such as the Man Booker International prize are doing their job if they bring relatively unknown authors to new readers. If you’ve missed out on László Krasznahorkai’s writing so far, here’s a potted history.

This Hungarian novelist and screenwriter has long been an open secret in some circles, and was described by Susan Sontag as the “contemporary Hungarian master of the apocalypse”. If you are among his admirers, we’d love to hear from you in the comments.

For starters, how do you pronounce his name?

[ˈlaːsloː krαsnαhorkα.i] That’s in phonetic English – for other languages, the author himself has provided some help.

Who is he?

Considered by many to be the most important living Hungarian author, Krasznahorkai was born on 5 January 1954, in Gyula, Hungary, to a lawyer and a social security administrator. He studied law and Hungarian language and literature at university, and, after some years as an editor, became a freelance writer. His first novel, Satantango (1985), pushed him to the centre of Hungarian literary life and is still his best known. He didn’t leave Communist Hungary until 1987, when he travelled to West Berlin for a fellowship – and he has lived in a number of countries since, but returning regularly to Hungary.

In the early 1990s, he spent long periods of time in Mongolia and China, and would later explore Japan – all of which resulted in aesthetic and stylistic experiments and changes in his writing. While writing the novel War & War (1999), he travelled in Europe and lived in Allen Ginsberg’s flat in New York, where the legendary Beat poet advised and helped him. According to his publishers, he now “lives in reclusiveness in the hills of Szentlászló”. His main literary hero is, he says, Kafka: “I follow him always.”

Which are his main translated works, and where should you start?

He’s known for his uncompromising style (the 12 chapters of Satantango each consist of a single paragraph) and is often labelled as postmodern. Don’t let that put you off, though. Five of his fictional works have been published in English so far, in translations by Ottilie Mulzet and George Szirtes, who will share the £15,000 translation prize that goes with the Booker.

Satantango (1985)

Satantango (1985)

His first and most famous novel. It tells the story of life in a disintegrating village in a dystopian communist Hungary, where a man called Irimias, long thought dead and who may be a prophet, a secret agent or the devil, appears out of nowhere and begins to manipulate the remaining citizens. According to the Guardian review, this is “a monster of a novel: compact, cleverly constructed, often exhilarating, and possessed of a distinctive, compelling vision – but a monster nevertheless. It is brutal, relentless and so amazingly bleak that it’s often quite funny.” It won the 2013 best translated book award in the fiction category.

The Melancholy of Resistance (1989)

This comedy of apocalypse is set in a town where a mysterious circus, whose only attraction is an enormous whale mounted on a truck, unnerves inhabitants and gives the local would-be tyrant Mrs Eszter what she sees as a perfect opportunity to manipulate the populace.

The form is stream of consciousness, with minimal punctuation. Translator Szirtes described it as “a slow lava flow of narrative, a vast black river of type”.

It won the book of the year award in Germany in 1993.

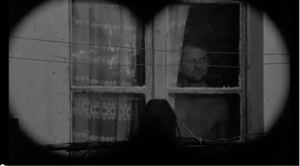

How about the films?

Both these novels have been made into films by his friend, Béla Tarr, in a collaboration which began with Kárhozat (Damnation) in 1988, and includes aseven-and-a-half-hour black-and-white version of Satantango. This took seven years to make and was released in 1994. Their collaboration continues.

What do the International Booker judges say about him?

Krasznahorkai was chosen from 10 contenders for the £60,000 prize for “an achievement in fiction on the world stage”.

The official citation:

Chair of judges Marina Warner said:

What about his other prominent admirers?

“The contemporary Hungarian master of apocalypse who inspires comparison with Gogol and Melville” – Susan Sontag

“The universality of Krasznahorkai’s vision rivals that of Gogol’s Dead Souls and far surpasses all the lesser concerns of contemporary writing” – WG Sebald

In his own words

Quotes from the novels

Useful links for further reading

- This Guardian interview from the 2012 Edinburgh book festival (“This is the result of 10,000 years? Really?”)

- This review of Satantango, from when it was published in English in 2012.

- Madness And Civilization: The very strange fictions of László Krasznahorkai, from the New Yorker.

- This interview in the White Review (“The similarity [betweeen the time he started writing and the present] is astounding. Everything seems to have changed and yet everything is essentially the same.”)

- He Rarely Stops Writing: a New York Times piece on how he found a US audience.

- The Man Booker International 2015 contenders in their own words

- His own website is very extensive and a brilliant source for all things Krasznahorkai.

Have you already read Krasznahorkai, in Hungarian or in translation? Do let us know your thoughts in the comments.

沒有留言:

張貼留言