中共開國上將之女向文革受迫害師生道歉

更新時間 2014年1月13日, 格林尼治標準時間04:20

在毛澤東發動和領導的文革中有成千上萬人被打死。

中共開國上將宋任窮的女兒、文革紅衛兵領袖宋彬彬周日(1月12日)向文革受害師生公開道歉。

宋彬彬還對她當年所在的北師大女附中被造反學生打死的副校長卞仲耘表示永久的悼念和歉意。據報道,1966年8月18日,當在天安門城樓上檢閱紅衛兵的毛澤東得知向他獻紅衛兵袖章的宋彬彬的名字是「文質彬彬」的「彬」字時便說,「要武嘛」。

報道說,宋彬彬隨後發表署名「宋要武」的文章《我給毛主席帶上紅袖章》。但宋彬彬否認文章為她所寫,並否認曾改名宋要武。

反思文革

在周日舉行的北師大女附中老三屆學生和老師的聚會上,宋彬彬說,她很久一直盼望能有這麼一個向當年遭受迫害的老師和同學道歉的機會。她說,北師大女附中的文革是從1966年6月2日她所參與貼出的第一張大字報開始的。學校的正常秩序從此遭到破壞,許多老師受到傷害。

宋彬彬向當時的所有老師和同學表示道歉。她說,希望她的道歉能夠引起大家的反思,並說,只有進行了真正的反思才能走的更遠。

宋彬彬還說,她希望所有在文革中做過錯事、傷害過老師同學的人,都能直面自己,反思文革,求得原諒,達成和解。

文革中紅衛兵的打人之風很快由學校蔓延到社會。據中國媒體報道,在1966年8月下旬至9月底的40多天裏,僅北京一地就有1700餘人被打死。

(撰稿:沙漠/責編:伊人)

宋任穷- 维基百科,自由的百科全书

News for 宋任窮

- 臺灣新浪網 - 19 hours ago廣州默客文化傳播有限公司總經理@葉恭默介紹,宋任窮之女宋彬彬(宋要武)曾在文革暴毆卞校長,今天回國道歉了。 華夏時報社長@張寶林稱,據其 ...

與FT共進午餐:陳小魯

FT中文網總編輯張力奮:低調的陳小魯,陳毅元帥之子,文革初期的學生領袖。最近他就文革期間行為道歉,成為新聞人物。午餐,約在他的母校——北京八中對門的一家茶社。他說,希望中國能回到井岡山時期。

2013.11.8

十一點半,陳小魯推開“慶宣和”會所養心廳的門。他匆匆趨前,握手打招呼。我們頭一回見面。沒有寒暄,他直奔主題,急著問:“你看是先談話,還是……”他朝正中央那張紅木大餐桌掃了一眼。我說,我們邊吃邊談吧。

我請陳小魯訂一個午餐地,最好有些故事的。他選了北京西城興盛街上的這家會所兼茶社。他說,這是朋友的地方,也是他的母校——北京八中同學會的大本營。現在他是八中同學會的會長。下車時,我才注意到,會所的正對面,就是八中校門。而“八中”正是向來低調的陳小魯最近成為新聞人物的直接導因。

平頭短髮,多半已銀白,一米八的高個子,陳小魯身著一件休閒的米黃夾克衫,拉鍊提得很高,幾乎到了軍裝風紀扣的位置,領口露出裡面紅褐色襯衣一角。

兩人坐定,佔了這張十人圓桌的一隅,有些孤獨。窗外,京城有霧霾,給室內投下的是陰暗和灰濛,很難刺激食慾和味蕾。這是北京時下典型、有最低消費的高檔會所包間:四、五十平米的樣子,紅木格調,鋪著地毯。進門是沙發會客區,中間一大塊,大圓餐桌,靠窗立著一個書桌大小的大茶几,是茶道。

小魯問,咱們吃什麼呢?他招手喊來服務員,得知他的朋友、會所老闆已安排了標準套餐,席間的氣氛立時輕快起來。初次見面,要在碩大的餐室,一對一,協商吃什麼的問題,畢竟有些擰巴。

1966年,文革爆發時,陳小魯就讀高三。他是北京知名度頗高的學生領袖,八中文革委員會主任,之後又發起組建文革中第一個跨校際的紅衛兵組織——“西糾”。

新聞在他身上聚焦,更因他的“紅二代”特殊身份:中共高層領導人、曾任副總理和外交部長的陳毅元帥之子。見過陳小魯的,都說他的容貌與他父親陳毅酷似。坐在他跟前,你不得不感嘆基因的力量,甚至有剎那間的幻覺,彷彿陳老總再世。

生於1946年,陳小魯今年67歲,已到了文革時他父親的那個年齡。前不久,他就文革期間的行為向當年遭受批鬥迫害的老師鞠躬道歉,重提反思文革,引發國內外輿論關注。

餐桌中央的轉盤上,標配的菜多已上齊。兩位食客,動作並不積極。我們各自喝著海參湯,片刻的沉默。轉盤上,刺身三文魚,月牙骨,鄉巴佬豆干,絲瓜炒蝦仁,小炒驢肉,安靜地趴在那兒。

他說,十月初,他代表當年八中同學向老師正式道歉,就在這家會所的另一個包間。

我問起正對門的母校。他說,已全無八中當年的影子。紅磚樓、鄰近的胡同和操場都拆了。他說起文革初年有關八中的細節,用的完全是當時的語言,人和事,時間與地點,校長書記,黑幫,西糾,靠邊站;6月8日,工作組進校;6月9日,校領導靠邊站;6月10日或11日,工作組召集開會,讓他講話;武鬥。批鬥。自殺。他把我當成了一位當年老同學,半是回憶,半是確認。這些細節,他應該已經敘述過很多遍。在他眼裡,所有人都是局內人,都有份。

我把話題拉回到“道歉”那天。

問:那天你代表同學道歉,有沒有當年的老師雖健在,但最後決定不來的?

答:好像能來的老師都來了。我之所以要道歉,是因為我們的造反破壞了學校正常秩序,才導致了侵犯人權,踐踏人格尊嚴的行為。不然的話發生不了。我道歉時沒有提及任何人,我沒有把它歸罪於毛澤東、或歸罪於“四人幫”。我覺得,反思就是自己的事情。

問:再過兩年多,文革爆發就五十年了。最近究竟是些什麼事情觸發了你公開道歉的念頭?

資料圖:“文革”結束後,陳小魯等校友在八中的校慶活動中與老師握手

其實我對文革的反思從66年8月就開始了:中山音樂堂批鬥會的武鬥,校黨支部書記不堪忍受虐待而自殺都給我心靈巨大的震撼,所以我發起組織了“西糾” 。1988年我們組織同學會,90年同學會設立獎教金,都是反思的結果,是順理成章的事,不是突發奇想。

現在有些人對文化大革命持肯定的態度,認為文革就是反貪官。文革失敗了,走資派上台。現在很多年輕人,中年人並沒有經過文革,認為那是老百姓的盛大節日,打貪官。另外一點,最近很多記者採訪我,認為文革有回潮,特別提到重慶。我說不是回潮,文化革命雖然過去了,被否定了,但是造成文化革命的基因還在。什麼基因?就是一種暴戾之氣。

我最有感觸的是2011年老百姓反對日本購買釣魚島,國內有遊行。為什麼打日系車的車主,都是同胞?有的被打得很慘。當時不是一個人哪!光天化日,大庭廣眾之下,那麼多人,為什麼沒有人出來阻止,來保護日系車主?人有暴戾之氣,少數人的這種暴戾之氣是能綁架群眾的,威嚇群眾的。

文化革命為什麼出了問題呢?就是因為維繫社會的一套制度,政府、警察、公安全部取消了。首先校領導變成批鬥對象,老師管不住學生,學生確實自由了,文化革命允許你自己成立什麼組織,成立紅衛兵,成立戰鬥隊,這都是社會組織。共產黨什麼時候允許成立過這種組織?特別是這些組織都是政治性組織。毛主席搞大民主。這些群眾組織起來後就按照自己的意願行事,就把惡的那面發揮出來了。

文化革命後來是遭到了否定,但是解決問題沒有呢?我得出一個結論,文化革命是違憲,兩條:一個叫造反有理。既然造反有理,誰不造反呢?那不造反就沒理了。你遵守正常的秩序,你服從這樣的領導,那都是沒理的事。還有一個叫做群眾專政。群眾專政是什麼意思?就是群眾想把你怎樣就怎麼樣,可以不經任何公安的偵查、檢察人員的起訴和法律的裁決,都沒有。很多人就這樣死於非命,或身心受到迫害和打擊。反觀現在,政府的暴力執法時有所聞,老百姓的暴力爭鬥也時有所聞!

文革從來就沒有真正離開過我們!它的基因還在作祟。記者來採訪,我一般會反問一下,哪年出生的,有的70後,有的80後,甚至有90後的。我說你們回憶一下,從小學、中學到大學,講過憲法沒有?講過法制沒有,有沒有講過公民的權利和義務?他們回答,都沒有!

問:聽到一種看法,你在文革中並沒有打人,因此不必道歉。或認為,這是作秀!

答:是有同學給我發短信,說如果要道歉的話,你也是最後一個!但是,當時八中有一千多名學生,並不是人人都造反了,八中有許多幹部子弟,也不是人人都造反了。我造反了,而且是頭頭,所以應該反思,應該道歉。

問:現在的問題是,執政黨和國家是不是應該對當年這段慘痛的歷史作更深刻的反省?答:我是這麼看的,不能說政府和執政黨一點反思沒有,我們不是有一個關於歷史問題的若干決議嗎?它對文化革命是徹底否定的。反思夠不夠呢?顯然是不夠的。如果反思充分的話,你首先應該強調憲法的權威,強調公民的權利和義務,你應該在學校裡開這個課,為什麼沒有做到?一直到現在都沒有。我問那些記者,他們都說沒有。所以就是反思不夠,只是把它作為一個政治問題或者路線問題,就過去了,並沒有看到文革這種基因以及人性之惡的那一面。

問:中國近百年的歷史,無法避開毛澤東這個巨大因素與他的影響力。你父親和毛澤東在中共革命的早年就有合作,井岡山時期還曾領導過毛,兩人私交也比較特殊。小時候,你們全家就住在中南海,跟這位共和國的締造者有近距離接觸。你覺得,毛澤東倒底是怎樣一個人?

答:他是領袖型人物。毛主席和很多共產黨領袖一樣,有救世主的情結,要改變世界,救民於水火,他有他的一套理念,並為這套理念而奮鬥。當然他這個人很特殊,一般人做不到:你既然打下了天下,應該功德圓滿了。他卻搞一場文化大革命把自己建立的那套東西再打掉。

問:是不是說,他做了皇帝,還要繼續革命?

答:對啊,他並不滿足啊。當然,毛主席發動文化革命可能有種種因素,包括他對劉少奇的不滿。但是很重要的一個因素是,他認為當時中國共產黨內出現一種官僚主義傾向,可能會步蘇聯的後塵。

問:你相信毛澤東講的話嗎?他的言與行有沒有矛盾?

答:兩種情況,在重大的哲學問題上,我相信他是真心的。但是到了具體問題,比如對某個人的評價,講他壞和好,就不一定,完全是權宜之計了。

問:下個月,就是毛澤東一百二十週年誕辰了。當年你在中南海游泳池見到的那個慈善的毛爺爺,回頭看,你如何評價?

答:我的評價還是一樣,有功有過,功大於過。經過革命戰爭,建立新中國,最後把中國整合起來的是毛澤東。後來改革開放取得的很多成就,國際地位的上升也好,和那時的共產黨和毛主席打下的基礎,還是有關聯的,而且不是一般的關聯。他還是一個領袖吧,有功有過。而且,他對中國的影響將是深遠的。

問:今年12月26日他生日那天,假定上天讓他走出紀念堂,放個假,看一眼當下的中國,你覺得毛主席會說些什麼?

答:他肯定不滿意了,因為貧富差距。他搞文化革命很重要的因素,是他要由下而上地揭露體制的黑暗面。你可以說他是民粹主義,或者是烏托邦。這是他的理想。關鍵問題是,為了這個理想,他沒有走民主法制的道路,還是採取另一場革命。

問:他發起文革,破壞了整個國家的秩序與運行,社會陷入混亂,生產停頓。作為國家的最高領袖,他不明白這場革命對全中國的致命影響?

答:他認為,這是可以付出的代價。包括打倒老戰友,他覺得這個代價是要付出的,就像打仗一樣,殺敵一千,自損八百。我覺得他的思想就是這樣,我就是要試一試。這個東西是比較要命的,一試就試了十年。到了晚年,毛的心情比較淒涼,他知道這個文化革命失敗了。

問:你父親因對文革的一些做法不滿,說了些話,被毛澤東批判為“二月逆流”,很快遭到邊緣化。1972年去世。毛澤東最後一刻決定出席陳毅追悼會,穿著睡衣趕到八寶山公墓。當時你作為家屬在場,毛澤東當時什麼樣的心情?

答:主席對我父親有感情。兩人在井岡山相識,也曾有些恩怨。我父親被批“二月逆流”時,當時認為他的講話是反林彪的。但後來證明,林彪跑了,陳毅沒跑。毛主席可能對我父親有一份愧疚之心。那天,在八寶山休息室裡,他說了四十多分鐘話。大意是,陳毅是立了大功勞的,是堅持革命路線的,和項英不一樣。他特別點了項英;然後跟我們小輩講,你們還年輕,你們不懂世事;而後,又講到林彪跑了。當時,西哈努克也坐在那裡。他說,我告訴你林彪跑了,接班人跑了。

問:從文革開始,我看你的經歷,很坎坷。你好像很早就開始對政治和權力保持一段距離?

答:也不能這麼說,我是一個理想主義者,我受黨的教育很深,我相信這個,現在還是這樣。有人問我,你認為中國當下怎麼樣?你希望看到怎樣的中國?我說,我希望回到井岡山時期:朱老總一軍之長,四十歲要挑糧上山,毛委員和紅軍戰士都是一樣的伙食。共產黨的理想,當年之所以有力量,按毛主席的講法,就是官兵一致,軍民一致,瓦解敵軍。國民黨士兵在白軍裡面就怕死,到了紅軍就勇敢,什麼使他轉變得這麼快?就是平等、民主。他到部隊一看,共產黨的軍長跟我一樣,還挑糧,這個反差太大了,國民黨軍官能做到嗎?這裡有軍事民主,有經濟民主,還有士兵委員會,有什麼意見可以說,他立刻就變化了。這是為我打仗,我不是為別人打仗,我不是吃糧當兵,我當兵是為了爭取自己的權益,所以他就勇敢。不是靠你宣傳,最大的宣傳教育在於實際行動。戰爭年代,共產黨的基層幹部傷亡是最大的,共產黨員傷亡是最大的。我們在部隊當兵的時候也一樣,最後的辦法就是幹部帶頭,喊共產黨員跟我上!

問:你說的這種軍事共產主義,可能只有在一個政黨在野的情況下才做得到吧?我們不可能重新回到那個年代吧?

答:我不期望完全能回到那個年代,三分之一也可以。對待老百姓得好一點吧,對待自己要求嚴一點吧。朱老總挑糧可不是一百米、二百米,那是從黃洋界一千五六百米的高山,從山腳挑到山頂。可不是咱們(領導人)現在種樹,坑別人都幫你挖好了,樹也放進去了,你就弄上幾鍬土。這個示範作用,是很重要的。現在不可能回到那個年代了。但在精神上起碼能有所要求。你當官就要尊重老百姓吧。

問:小魯,你住在北京,不會不感受到老百姓對太子黨或者“紅二代”的反感,甚至厭惡?

答:網上都看到了。相反,私下里,人家給你面子。同樣的,我也得給別人面子。

問:不少“紅二代”有很深的“紅色情結”。是否說白了,他們覺得,是老爸打下的紅色江山。作為後代,他們有份?

答:沒有,我沒這個想法,我最反對這種想法。江山不是你老爸打下來的,犧牲那麼多戰士,是老百姓打下來的,這是我父親對我們很重要的教育,父親講“一將成榮萬骨枯”。我們說是父輩打下來的,父輩包括戰士和老百姓。

問:你這輩的“紅二代”也上一定年紀了,懷舊了,經常會有些聚會。如果碰在一起,談的最多的是什麼?

答:有什麼主題就談什麼主題,比如像賀老總那時候有什麼紀念活動,那就講賀老總。也不排除談論一些歷史問題,一般這種場合下,大家也都不會公開地爭吵、爭論。

問:“紅二代”對當下的現實怎麼看?

答:當然是不滿居多,特別是前幾年。一是對貪腐問題很反感,是有共識的。另外就是天氣。霧霾是我們常談的話題,因為它直接影響到我們的生活了。

問:貪腐問題,一般的老百姓有抱怨或者情緒激烈。你說,“紅二代”或者高幹子弟也在抱怨貪腐,很多老百姓可能會不理解。在他們看來,你們就是最大的利益獲得者。

答:真正的“紅二代”,和現在更年輕的“官二代”不同。所謂“紅二代”,指的是1949年共和國成立之後,文革前那批中共革命幹部的後代。那時,行政級別13級以上的算是高級幹部。其實,沒當高官的“紅二代”,生活都很普通。他們中的大多數人也就是中等收入,生活得很好的不多,當高官的,發大財的不多。為什麼很多“紅二代”願意參加外地的紀念活動,一個原因就是他們連自己旅遊的錢都沒有。當然了,他們的日子比老百姓好一點,但也有限。像我們這樣經了商的,好一點。話又講回來,像我的企業,我是納稅人,我不吃皇糧,我是自食其力的……我們八中的“紅二代”,很多副部級以上的干部,貪腐的比例很少,說明這代人受過傳統的教育,有他的擔當,有他的抱負,也有他的自律。老百姓對“紅二代”有這樣的情緒我也很理解,比如最近審判薄熙來,老百姓好像認為“紅二代”都跟薄熙來一樣,可能嗎?

問:你熟悉或了解薄熙來嗎?你們兩人的父親,陳毅和薄一波,都曾出任過國務院副總理。

答:小時候,我們接觸不多,薄熙來年紀比我小一點,他在四中,我在八中。我當時跟他哥哥薄熙永接觸多一些。後來他就去大連當官了。其實我對薄熙來的印象,還是不錯的。這個人有幹勁,有一些抱負,比較張揚一點。他是不是有野心,咱們也搞不清楚,其實他到了那個位置,再想往上走走,也是人之常情。我覺得他最大的問題就是為了打黑快出成果,縱容王立軍這樣的酷吏去搞逼供。但這個問題我認為不是他個人問題,這個制度在那兒擺著。你以為這種做法就只在重慶啊?!現在揭發出來的很多單位都是差不多的。他做的最過分的一件事是把律師抓起來,這下子觸犯眾怒了。所以我始終有一句話,重慶也好,任何地方也好,都不是回潮。是文革的基因,在那裡作祟。

問:薄家在文革期間遭受的迫害,據說比你們陳家的境遇更悲慘,多人遭關押。但薄熙來從政之後,動用的也是當年的殘酷手段。難道政治就是這樣?

答:對!搞政治有潛規則,極端實用主義,為達目的,不擇手段,而且缺乏有效的監督和制衡。你在這個國家當官,當久了,就習慣成自然了。有人給我擋道,我就想把你搬開,至於用什麼手段,那再說了。我想種樹,你反對,那我就罷你的官。

問:像這樣心態的中國官員現在多嗎?

答:太多了!這是我們面臨的一個大問題,我講的文革也是這個問題,你想成事,有抱負,是好事。但總要有個界限,有一個底線。中國發展到現在,咱們要採取文景之治,我始終主張本屆政府搞文景之治,因為欠債太多了。中國高速發展三十多年,你欠了多少債?環境債,污染債,水資源短缺,產能過剩,怎麼辦?就是要調整結構,就是咬咬牙忍住。現在老想著兩頭撈好處,這是不可能的,不現實。人民幣超發,你就得少發一點,少發一點肯定會影響經濟發展,掉下來就掉下來一點,沒有關係。政府手裡還有那麼多錢,你可以去救救老百姓。你老搞大規模的投資,投資又沒有效益,怎麼辦?

問:薄案發生後,你吃驚嗎?

答:當然吃驚!殺人,這是不可想像的。別的我倒不吃驚,貪腐也不是他一個人貪腐,有的比他貪的還多!有些事他可能也不知道,我看他的心思不在錢。反正你管不住自己的官員,就會出大問題。

問:1976年,毛澤東去世那年,你從部隊調入總參二部。1981年冬,你被派往倫敦任中國駐英武官助理、後升為副武官,待了四年。應屬較早一批接觸西方的中國高幹子弟。

答:那段經歷是一種啟蒙。出國前有培訓,看的材料說的還是倫敦霧。冬天,到了倫敦一看,藍天白云不說,底下青草如雲,蓋著白雪,一下子就顛覆了。什麼倫敦霧啊?!我們當時要解放全世界三分之二的被壓迫人民。但到這裡一看,好像這三分之二人民生活得比我們好。非常強烈的反差。你就知道了,過去你聽到的東西不那麼真實了,就要重新思考到底怎麼回事,重新觀察資本主義社會有什麼弊病,什麼優勢。你說它是垂死、腐敗的,這個論斷就有些問題了,它的制度當然有它的長處。所以當時老鄧提出來改革開放也很正常,人家經濟發達、工業發達,科技發達。

問:你從政的最後一站,是八十年代中期任職中共中央政治體制改革研討小組,後出任政改研究室社會局局長。時任中共總書記是趙紫陽,“六四“後遭罷黜,政改研究室也遭解散。這段經歷,是否改變了你後半生的選擇,決定徹底退出政壇?

答:對我個人來講,是改變了。如果沒有這個事,我可能還在軍中發展,也不會輕易下海。文革以後我們還是對國家充滿了信心,充滿了希望,覺得四人幫粉碎了,我們的體制應該很好地改變一下。後來經濟體制改革取得很多成果。到了86年、87年,中國是蒸蒸日上的。我之所以最後離開體制,是我在“六四”之後發現,很多東西根本沒變,還是老辦法。我跟當時的工作組講得非常明白,我覺得你們在搞什麼呢?不就是“四人幫”那套嗎?工作組說,你怎麼這樣講呢,我說我就是這麼認為的。

問:你是一個“紅二代”,當時決定這輩子不再從政,糾結嗎?

答:我不當官了,毅然決然,沒有什麼說的,道不同不相與謀,我從來就是這樣的。在部隊時,讓我說違心話,我不願意,說就走唄,天下大的很。我幼年的成長環境比較寬鬆。我父親從不問我入黨入團的事,沒有這種要求。第二,你學習成績及格就行。別到處胡來,不要當紈絝子弟就行了。

問:你容貌很像你父親,你的性格像他嗎?

答:我父親比較灑脫,我更瀟灑一點。我都離開了這個體制,不是更瀟灑嗎!我父親沒法離開這個體制。他那麼大官,想離開也離開不了。所以你當了高官反而有問題,就在我那個位置上退下來,誰也不管你,天高皇帝遠。我後來就自詡為“無上級個人”。沒人當我的上級,比如我要出國,辦個簽證就完了。過去你要當官,還有政治審查你能不能出國,有限制,如果大官的話,一年只能出國兩次。

問:1992年,你以上校軍銜轉業,下海從商。父親的背景、體制內的人脈,還是能幫上忙吧?

答:有一些,不但是體制內的朋友,包括我父親的名聲,都有作用。但是我們經商並不完全靠這些玩意。

問:你覺得現在當官的,和你父親那一輩當官的有什麼不同?

答:那時當官的,還有一個主義,還有一個信仰在那。現在當官的,就不知道了,往往是人身依附的關係更重,眼睛向上看的更多些。那時當官的也不能說眼睛不向上看。

問:你父親如果還活著,以他的性格,對當下的中國時局,會說些什麼?

答:我覺得,他還是老一代的觀點,對現在的貪腐他肯定不滿意,對收入分配的差距他肯定不滿意,同樣對現在的環境污染他肯定也會不滿意。但是經濟發展這方面,不管怎麼樣,我們綜合國力增強了。說句實話,對中國的革命,我的基本觀點就是毛主席那兩句話,道路曲折,前途光明。中國的建設也好,發展也好,就是這樣,它不會是一下子就搞好的。但從整體上來講,現在已經相當開放了,你說搞文化革命還能一呼百應嗎?不可能了。

問:“六四”事件,是共和國歷史上的的一個黑疤或陰影,這個事情最後會如何了結?

答:這有一個時機問題,還有一個性質認定問題。如果性質認定解決了,就等時機了。從根本上來講,文化革命的教訓,以至後來的一些挫折的教訓就是,如果不從深層次解決違憲的問題,你解決不了這個問題。領導人是來來去去的。現在一個領導人頂多幹十年,每個領導提出一些新的口號,十年以後就要換一個口號。但是法律這個東西是長遠的,它決定著國家的體制與制度。所以我覺得治國也不難,按照憲法辦事就行了。憲法不足的地方可由其他的法律來補充,實在不行,可以修憲。治國是有程序的,國家有序的運作,才能把國家真正整合起來。

問:中共十八屆三中全會快到了。海內外輿論都很關注,中國的下一步會怎麼走。你與習近平總書記是同輩人,背景也相似,有怎樣的期待?

答:我沒啥期待。期待也沒有用,關鍵在中央決定。現在有各種說法,我覺得這次三中全會重點應在經濟體制改革吧,比如土地流轉,金融改革等。經濟層面的改革會多一些,政治體制改革會滯後一點,不會有太多的動作。咱們說句老實話,你依靠的隊伍還是原來的隊伍,也沒有換人,這些人執行政務,會完全尊重法律、尊重人權嗎?不可能的,所以這個事情得慢慢來。要我說,中國的政治體制改革,可能要一百年,你得培養幾代人。

問:你說慢慢來。中國還能承受慢慢來的代價嗎?

答:問題不大吧,現在也不愁吃穿。多數老百姓可能對生活不大滿意,但過得去。他不見得百分之百地支持這個政權,但是也沒覺得這個政權有太多的壞處。另外現在還有一個國際比較的角度,好像西方也不是太美妙,這個給中國政權的合法性提供很大的空間。中國政府不管怎麼樣,還在做事吧,投資也好,扶貧也好。

問:你是說,眼下就東西方發展態勢的對比,中國不太可能在政治制度上做一些大的改革?

答:再說,就是十年不干什麼事,維持現狀也能混得下去。你知道國內有多少錢啊,什麼事幹不成啊!最近英國高層訪華,我看英國媒體上說,英國政府是在對中國磕頭獻媚。最近走了很多國家,每個地方都有中國人的聲音,有的是政府的聲音,有的是普通老百姓的聲音。人家對中國人一方面很不屑,同時也很敬重,畢竟跟過去不一樣。過去你是可有可無的,中國人算什麼?東亞病夫,你有什麼了不起。人家可能不屑於理你,可能對你同情一點,給你點施捨。現在不一樣了,現在你是大戶,他看著你覺得嫉妒。不一樣了。

問:“紅二代”之間,有沒有這樣的習慣,就是對當政的“紅二代”領導人進言,就國家大事提提意見?

答:我不知道別人怎麼樣,我一般沒有。為什麼呢?如果他當了官,你講話他愛不愛聽,這是第一;另外,好不容易聚到一塊,對他是個放鬆的機會,你給他提個問題,幹嘛呢?人家本來跟我們聚一塊,是聊聊天,回憶過去,對他來講是放鬆。官場那麼緊張,你突然說你這事做的不對,至少我不會這麼說,除非他提出來,要聽我的意見。我從來不寫信,我要寫就寫公開信,交給誰都不好。

午餐臨近尾聲。

我問小魯,現在閒下來了,做些什麼?他說,他和太太(粟裕將軍的女兒)經常出國旅遊,已經走過了104個國家與地區。每年外出旅遊平均一百天。在提到台灣、香港、澳門時,他都特別在每個地名後加上“地區”兩個字。陳毅當過近10年的中國外長,小魯是武官出身,這些國家利益的細節表述至關重要。

他送我厚厚一冊他編輯的陳毅影集,書名是他父親的一句詩:“真紅不枯槁”。我們移到大餐桌的另一半。小魯借了一台會所的手提電腦,讓我看看“道歉會”當天的照片。因不是他所熟悉的電腦,照片在屏幕上頻頻跳脫,他焦急起來。他指著照片上一位年逾古稀的女老師說,道歉會上,是她站起來,向我鞠躬,謝謝我在文革時保護了她。

餐桌上,還留下不少菜。這是中國常見的情景。想起近來習總書記與中央政府倡導節儉,頗有些內疚。與陳小魯道別時,他正坐在餐桌的手提電腦前,專心地查找什麼文件。他抬了抬頭,與見面時一樣,沒有客套,匆匆作別。

走出會所,午後的秋陽,有些蕭瑟,門前的街道亮堂精幹了些。八中校門口,兩位管停車的老大媽,扎著紅袖章,正在值勤;校門口,一位穿著準警察制服的年輕保安也在值勤。他們都在維持各自的秩序。

47年前,20歲的陳小魯就是在這裡走向一場瘋狂而殘酷的血色革命。這頓午餐,就像是他邀我直面一位無情的歷史證人。街對面的八中,咫尺天涯,是伴隨他一生、無法逃避的十字架。這條十字架,陳小魯扛得很累,有些是父輩的紅色遺業,有些是自身悔悟反思,同道與叛逆,理想與矛盾,難斷是非。

------

慶宣和會所,北京

刺身三文魚

巧拌月芽骨

鄉巴佬豆干

衝浪話梅參2份

剁椒小黃魚2份

絲瓜炒蝦仁

小炒驢肉

清炒雞毛菜

果盤2份

刀削麵2份

美點雙拼

藍莓1瓶

528元人民幣/位

資料圖:“文革”結束後,陳小魯等校友在八中的校慶活動中與老師握手

其實我對文革的反思從66年8月就開始了:中山音樂堂批鬥會的武鬥,校黨支部書記不堪忍受虐待而自殺都給我心靈巨大的震撼,所以我發起組織了“西糾” 。1988年我們組織同學會,90年同學會設立獎教金,都是反思的結果,是順理成章的事,不是突發奇想。

現在有些人對文化大革命持肯定的態度,認為文革就是反貪官。文革失敗了,走資派上台。現在很多年輕人,中年人並沒有經過文革,認為那是老百姓的盛大節日,打貪官。另外一點,最近很多記者採訪我,認為文革有回潮,特別提到重慶。我說不是回潮,文化革命雖然過去了,被否定了,但是造成文化革命的基因還在。什麼基因?就是一種暴戾之氣。

我最有感觸的是2011年老百姓反對日本購買釣魚島,國內有遊行。為什麼打日系車的車主,都是同胞?有的被打得很慘。當時不是一個人哪!光天化日,大庭廣眾之下,那麼多人,為什麼沒有人出來阻止,來保護日系車主?人有暴戾之氣,少數人的這種暴戾之氣是能綁架群眾的,威嚇群眾的。

文化革命為什麼出了問題呢?就是因為維繫社會的一套制度,政府、警察、公安全部取消了。首先校領導變成批鬥對象,老師管不住學生,學生確實自由了,文化革命允許你自己成立什麼組織,成立紅衛兵,成立戰鬥隊,這都是社會組織。共產黨什麼時候允許成立過這種組織?特別是這些組織都是政治性組織。毛主席搞大民主。這些群眾組織起來後就按照自己的意願行事,就把惡的那面發揮出來了。

文化革命後來是遭到了否定,但是解決問題沒有呢?我得出一個結論,文化革命是違憲,兩條:一個叫造反有理。既然造反有理,誰不造反呢?那不造反就沒理了。你遵守正常的秩序,你服從這樣的領導,那都是沒理的事。還有一個叫做群眾專政。群眾專政是什麼意思?就是群眾想把你怎樣就怎麼樣,可以不經任何公安的偵查、檢察人員的起訴和法律的裁決,都沒有。很多人就這樣死於非命,或身心受到迫害和打擊。反觀現在,政府的暴力執法時有所聞,老百姓的暴力爭鬥也時有所聞!

文革從來就沒有真正離開過我們!它的基因還在作祟。記者來採訪,我一般會反問一下,哪年出生的,有的70後,有的80後,甚至有90後的。我說你們回憶一下,從小學、中學到大學,講過憲法沒有?講過法制沒有,有沒有講過公民的權利和義務?他們回答,都沒有!

問:聽到一種看法,你在文革中並沒有打人,因此不必道歉。或認為,這是作秀!

答:是有同學給我發短信,說如果要道歉的話,你也是最後一個!但是,當時八中有一千多名學生,並不是人人都造反了,八中有許多幹部子弟,也不是人人都造反了。我造反了,而且是頭頭,所以應該反思,應該道歉。

問:現在的問題是,執政黨和國家是不是應該對當年這段慘痛的歷史作更深刻的反省?答:我是這麼看的,不能說政府和執政黨一點反思沒有,我們不是有一個關於歷史問題的若干決議嗎?它對文化革命是徹底否定的。反思夠不夠呢?顯然是不夠的。如果反思充分的話,你首先應該強調憲法的權威,強調公民的權利和義務,你應該在學校裡開這個課,為什麼沒有做到?一直到現在都沒有。我問那些記者,他們都說沒有。所以就是反思不夠,只是把它作為一個政治問題或者路線問題,就過去了,並沒有看到文革這種基因以及人性之惡的那一面。

問:中國近百年的歷史,無法避開毛澤東這個巨大因素與他的影響力。你父親和毛澤東在中共革命的早年就有合作,井岡山時期還曾領導過毛,兩人私交也比較特殊。小時候,你們全家就住在中南海,跟這位共和國的締造者有近距離接觸。你覺得,毛澤東倒底是怎樣一個人?

答:他是領袖型人物。毛主席和很多共產黨領袖一樣,有救世主的情結,要改變世界,救民於水火,他有他的一套理念,並為這套理念而奮鬥。當然他這個人很特殊,一般人做不到:你既然打下了天下,應該功德圓滿了。他卻搞一場文化大革命把自己建立的那套東西再打掉。

問:是不是說,他做了皇帝,還要繼續革命?

答:對啊,他並不滿足啊。當然,毛主席發動文化革命可能有種種因素,包括他對劉少奇的不滿。但是很重要的一個因素是,他認為當時中國共產黨內出現一種官僚主義傾向,可能會步蘇聯的後塵。

問:你相信毛澤東講的話嗎?他的言與行有沒有矛盾?

答:兩種情況,在重大的哲學問題上,我相信他是真心的。但是到了具體問題,比如對某個人的評價,講他壞和好,就不一定,完全是權宜之計了。

問:下個月,就是毛澤東一百二十週年誕辰了。當年你在中南海游泳池見到的那個慈善的毛爺爺,回頭看,你如何評價?

答:我的評價還是一樣,有功有過,功大於過。經過革命戰爭,建立新中國,最後把中國整合起來的是毛澤東。後來改革開放取得的很多成就,國際地位的上升也好,和那時的共產黨和毛主席打下的基礎,還是有關聯的,而且不是一般的關聯。他還是一個領袖吧,有功有過。而且,他對中國的影響將是深遠的。

問:今年12月26日他生日那天,假定上天讓他走出紀念堂,放個假,看一眼當下的中國,你覺得毛主席會說些什麼?

答:他肯定不滿意了,因為貧富差距。他搞文化革命很重要的因素,是他要由下而上地揭露體制的黑暗面。你可以說他是民粹主義,或者是烏托邦。這是他的理想。關鍵問題是,為了這個理想,他沒有走民主法制的道路,還是採取另一場革命。

問:他發起文革,破壞了整個國家的秩序與運行,社會陷入混亂,生產停頓。作為國家的最高領袖,他不明白這場革命對全中國的致命影響?

答:他認為,這是可以付出的代價。包括打倒老戰友,他覺得這個代價是要付出的,就像打仗一樣,殺敵一千,自損八百。我覺得他的思想就是這樣,我就是要試一試。這個東西是比較要命的,一試就試了十年。到了晚年,毛的心情比較淒涼,他知道這個文化革命失敗了。

問:你父親因對文革的一些做法不滿,說了些話,被毛澤東批判為“二月逆流”,很快遭到邊緣化。1972年去世。毛澤東最後一刻決定出席陳毅追悼會,穿著睡衣趕到八寶山公墓。當時你作為家屬在場,毛澤東當時什麼樣的心情?

答:主席對我父親有感情。兩人在井岡山相識,也曾有些恩怨。我父親被批“二月逆流”時,當時認為他的講話是反林彪的。但後來證明,林彪跑了,陳毅沒跑。毛主席可能對我父親有一份愧疚之心。那天,在八寶山休息室裡,他說了四十多分鐘話。大意是,陳毅是立了大功勞的,是堅持革命路線的,和項英不一樣。他特別點了項英;然後跟我們小輩講,你們還年輕,你們不懂世事;而後,又講到林彪跑了。當時,西哈努克也坐在那裡。他說,我告訴你林彪跑了,接班人跑了。

問:從文革開始,我看你的經歷,很坎坷。你好像很早就開始對政治和權力保持一段距離?

答:也不能這麼說,我是一個理想主義者,我受黨的教育很深,我相信這個,現在還是這樣。有人問我,你認為中國當下怎麼樣?你希望看到怎樣的中國?我說,我希望回到井岡山時期:朱老總一軍之長,四十歲要挑糧上山,毛委員和紅軍戰士都是一樣的伙食。共產黨的理想,當年之所以有力量,按毛主席的講法,就是官兵一致,軍民一致,瓦解敵軍。國民黨士兵在白軍裡面就怕死,到了紅軍就勇敢,什麼使他轉變得這麼快?就是平等、民主。他到部隊一看,共產黨的軍長跟我一樣,還挑糧,這個反差太大了,國民黨軍官能做到嗎?這裡有軍事民主,有經濟民主,還有士兵委員會,有什麼意見可以說,他立刻就變化了。這是為我打仗,我不是為別人打仗,我不是吃糧當兵,我當兵是為了爭取自己的權益,所以他就勇敢。不是靠你宣傳,最大的宣傳教育在於實際行動。戰爭年代,共產黨的基層幹部傷亡是最大的,共產黨員傷亡是最大的。我們在部隊當兵的時候也一樣,最後的辦法就是幹部帶頭,喊共產黨員跟我上!

問:你說的這種軍事共產主義,可能只有在一個政黨在野的情況下才做得到吧?我們不可能重新回到那個年代吧?

答:我不期望完全能回到那個年代,三分之一也可以。對待老百姓得好一點吧,對待自己要求嚴一點吧。朱老總挑糧可不是一百米、二百米,那是從黃洋界一千五六百米的高山,從山腳挑到山頂。可不是咱們(領導人)現在種樹,坑別人都幫你挖好了,樹也放進去了,你就弄上幾鍬土。這個示範作用,是很重要的。現在不可能回到那個年代了。但在精神上起碼能有所要求。你當官就要尊重老百姓吧。

問:小魯,你住在北京,不會不感受到老百姓對太子黨或者“紅二代”的反感,甚至厭惡?

答:網上都看到了。相反,私下里,人家給你面子。同樣的,我也得給別人面子。

問:不少“紅二代”有很深的“紅色情結”。是否說白了,他們覺得,是老爸打下的紅色江山。作為後代,他們有份?

答:沒有,我沒這個想法,我最反對這種想法。江山不是你老爸打下來的,犧牲那麼多戰士,是老百姓打下來的,這是我父親對我們很重要的教育,父親講“一將成榮萬骨枯”。我們說是父輩打下來的,父輩包括戰士和老百姓。

問:你這輩的“紅二代”也上一定年紀了,懷舊了,經常會有些聚會。如果碰在一起,談的最多的是什麼?

答:有什麼主題就談什麼主題,比如像賀老總那時候有什麼紀念活動,那就講賀老總。也不排除談論一些歷史問題,一般這種場合下,大家也都不會公開地爭吵、爭論。

問:“紅二代”對當下的現實怎麼看?

答:當然是不滿居多,特別是前幾年。一是對貪腐問題很反感,是有共識的。另外就是天氣。霧霾是我們常談的話題,因為它直接影響到我們的生活了。

問:貪腐問題,一般的老百姓有抱怨或者情緒激烈。你說,“紅二代”或者高幹子弟也在抱怨貪腐,很多老百姓可能會不理解。在他們看來,你們就是最大的利益獲得者。

答:真正的“紅二代”,和現在更年輕的“官二代”不同。所謂“紅二代”,指的是1949年共和國成立之後,文革前那批中共革命幹部的後代。那時,行政級別13級以上的算是高級幹部。其實,沒當高官的“紅二代”,生活都很普通。他們中的大多數人也就是中等收入,生活得很好的不多,當高官的,發大財的不多。為什麼很多“紅二代”願意參加外地的紀念活動,一個原因就是他們連自己旅遊的錢都沒有。當然了,他們的日子比老百姓好一點,但也有限。像我們這樣經了商的,好一點。話又講回來,像我的企業,我是納稅人,我不吃皇糧,我是自食其力的……我們八中的“紅二代”,很多副部級以上的干部,貪腐的比例很少,說明這代人受過傳統的教育,有他的擔當,有他的抱負,也有他的自律。老百姓對“紅二代”有這樣的情緒我也很理解,比如最近審判薄熙來,老百姓好像認為“紅二代”都跟薄熙來一樣,可能嗎?

問:你熟悉或了解薄熙來嗎?你們兩人的父親,陳毅和薄一波,都曾出任過國務院副總理。

答:小時候,我們接觸不多,薄熙來年紀比我小一點,他在四中,我在八中。我當時跟他哥哥薄熙永接觸多一些。後來他就去大連當官了。其實我對薄熙來的印象,還是不錯的。這個人有幹勁,有一些抱負,比較張揚一點。他是不是有野心,咱們也搞不清楚,其實他到了那個位置,再想往上走走,也是人之常情。我覺得他最大的問題就是為了打黑快出成果,縱容王立軍這樣的酷吏去搞逼供。但這個問題我認為不是他個人問題,這個制度在那兒擺著。你以為這種做法就只在重慶啊?!現在揭發出來的很多單位都是差不多的。他做的最過分的一件事是把律師抓起來,這下子觸犯眾怒了。所以我始終有一句話,重慶也好,任何地方也好,都不是回潮。是文革的基因,在那裡作祟。

問:薄家在文革期間遭受的迫害,據說比你們陳家的境遇更悲慘,多人遭關押。但薄熙來從政之後,動用的也是當年的殘酷手段。難道政治就是這樣?

答:對!搞政治有潛規則,極端實用主義,為達目的,不擇手段,而且缺乏有效的監督和制衡。你在這個國家當官,當久了,就習慣成自然了。有人給我擋道,我就想把你搬開,至於用什麼手段,那再說了。我想種樹,你反對,那我就罷你的官。

問:像這樣心態的中國官員現在多嗎?

答:太多了!這是我們面臨的一個大問題,我講的文革也是這個問題,你想成事,有抱負,是好事。但總要有個界限,有一個底線。中國發展到現在,咱們要採取文景之治,我始終主張本屆政府搞文景之治,因為欠債太多了。中國高速發展三十多年,你欠了多少債?環境債,污染債,水資源短缺,產能過剩,怎麼辦?就是要調整結構,就是咬咬牙忍住。現在老想著兩頭撈好處,這是不可能的,不現實。人民幣超發,你就得少發一點,少發一點肯定會影響經濟發展,掉下來就掉下來一點,沒有關係。政府手裡還有那麼多錢,你可以去救救老百姓。你老搞大規模的投資,投資又沒有效益,怎麼辦?

問:薄案發生後,你吃驚嗎?

答:當然吃驚!殺人,這是不可想像的。別的我倒不吃驚,貪腐也不是他一個人貪腐,有的比他貪的還多!有些事他可能也不知道,我看他的心思不在錢。反正你管不住自己的官員,就會出大問題。

問:1976年,毛澤東去世那年,你從部隊調入總參二部。1981年冬,你被派往倫敦任中國駐英武官助理、後升為副武官,待了四年。應屬較早一批接觸西方的中國高幹子弟。

答:那段經歷是一種啟蒙。出國前有培訓,看的材料說的還是倫敦霧。冬天,到了倫敦一看,藍天白云不說,底下青草如雲,蓋著白雪,一下子就顛覆了。什麼倫敦霧啊?!我們當時要解放全世界三分之二的被壓迫人民。但到這裡一看,好像這三分之二人民生活得比我們好。非常強烈的反差。你就知道了,過去你聽到的東西不那麼真實了,就要重新思考到底怎麼回事,重新觀察資本主義社會有什麼弊病,什麼優勢。你說它是垂死、腐敗的,這個論斷就有些問題了,它的制度當然有它的長處。所以當時老鄧提出來改革開放也很正常,人家經濟發達、工業發達,科技發達。

問:你從政的最後一站,是八十年代中期任職中共中央政治體制改革研討小組,後出任政改研究室社會局局長。時任中共總書記是趙紫陽,“六四“後遭罷黜,政改研究室也遭解散。這段經歷,是否改變了你後半生的選擇,決定徹底退出政壇?

答:對我個人來講,是改變了。如果沒有這個事,我可能還在軍中發展,也不會輕易下海。文革以後我們還是對國家充滿了信心,充滿了希望,覺得四人幫粉碎了,我們的體制應該很好地改變一下。後來經濟體制改革取得很多成果。到了86年、87年,中國是蒸蒸日上的。我之所以最後離開體制,是我在“六四”之後發現,很多東西根本沒變,還是老辦法。我跟當時的工作組講得非常明白,我覺得你們在搞什麼呢?不就是“四人幫”那套嗎?工作組說,你怎麼這樣講呢,我說我就是這麼認為的。

問:你是一個“紅二代”,當時決定這輩子不再從政,糾結嗎?

答:我不當官了,毅然決然,沒有什麼說的,道不同不相與謀,我從來就是這樣的。在部隊時,讓我說違心話,我不願意,說就走唄,天下大的很。我幼年的成長環境比較寬鬆。我父親從不問我入黨入團的事,沒有這種要求。第二,你學習成績及格就行。別到處胡來,不要當紈絝子弟就行了。

問:你容貌很像你父親,你的性格像他嗎?

答:我父親比較灑脫,我更瀟灑一點。我都離開了這個體制,不是更瀟灑嗎!我父親沒法離開這個體制。他那麼大官,想離開也離開不了。所以你當了高官反而有問題,就在我那個位置上退下來,誰也不管你,天高皇帝遠。我後來就自詡為“無上級個人”。沒人當我的上級,比如我要出國,辦個簽證就完了。過去你要當官,還有政治審查你能不能出國,有限制,如果大官的話,一年只能出國兩次。

問:1992年,你以上校軍銜轉業,下海從商。父親的背景、體制內的人脈,還是能幫上忙吧?

答:有一些,不但是體制內的朋友,包括我父親的名聲,都有作用。但是我們經商並不完全靠這些玩意。

問:你覺得現在當官的,和你父親那一輩當官的有什麼不同?

答:那時當官的,還有一個主義,還有一個信仰在那。現在當官的,就不知道了,往往是人身依附的關係更重,眼睛向上看的更多些。那時當官的也不能說眼睛不向上看。

問:你父親如果還活著,以他的性格,對當下的中國時局,會說些什麼?

答:我覺得,他還是老一代的觀點,對現在的貪腐他肯定不滿意,對收入分配的差距他肯定不滿意,同樣對現在的環境污染他肯定也會不滿意。但是經濟發展這方面,不管怎麼樣,我們綜合國力增強了。說句實話,對中國的革命,我的基本觀點就是毛主席那兩句話,道路曲折,前途光明。中國的建設也好,發展也好,就是這樣,它不會是一下子就搞好的。但從整體上來講,現在已經相當開放了,你說搞文化革命還能一呼百應嗎?不可能了。

問:“六四”事件,是共和國歷史上的的一個黑疤或陰影,這個事情最後會如何了結?

答:這有一個時機問題,還有一個性質認定問題。如果性質認定解決了,就等時機了。從根本上來講,文化革命的教訓,以至後來的一些挫折的教訓就是,如果不從深層次解決違憲的問題,你解決不了這個問題。領導人是來來去去的。現在一個領導人頂多幹十年,每個領導提出一些新的口號,十年以後就要換一個口號。但是法律這個東西是長遠的,它決定著國家的體制與制度。所以我覺得治國也不難,按照憲法辦事就行了。憲法不足的地方可由其他的法律來補充,實在不行,可以修憲。治國是有程序的,國家有序的運作,才能把國家真正整合起來。

問:中共十八屆三中全會快到了。海內外輿論都很關注,中國的下一步會怎麼走。你與習近平總書記是同輩人,背景也相似,有怎樣的期待?

答:我沒啥期待。期待也沒有用,關鍵在中央決定。現在有各種說法,我覺得這次三中全會重點應在經濟體制改革吧,比如土地流轉,金融改革等。經濟層面的改革會多一些,政治體制改革會滯後一點,不會有太多的動作。咱們說句老實話,你依靠的隊伍還是原來的隊伍,也沒有換人,這些人執行政務,會完全尊重法律、尊重人權嗎?不可能的,所以這個事情得慢慢來。要我說,中國的政治體制改革,可能要一百年,你得培養幾代人。

問:你說慢慢來。中國還能承受慢慢來的代價嗎?

答:問題不大吧,現在也不愁吃穿。多數老百姓可能對生活不大滿意,但過得去。他不見得百分之百地支持這個政權,但是也沒覺得這個政權有太多的壞處。另外現在還有一個國際比較的角度,好像西方也不是太美妙,這個給中國政權的合法性提供很大的空間。中國政府不管怎麼樣,還在做事吧,投資也好,扶貧也好。

問:你是說,眼下就東西方發展態勢的對比,中國不太可能在政治制度上做一些大的改革?

答:再說,就是十年不干什麼事,維持現狀也能混得下去。你知道國內有多少錢啊,什麼事幹不成啊!最近英國高層訪華,我看英國媒體上說,英國政府是在對中國磕頭獻媚。最近走了很多國家,每個地方都有中國人的聲音,有的是政府的聲音,有的是普通老百姓的聲音。人家對中國人一方面很不屑,同時也很敬重,畢竟跟過去不一樣。過去你是可有可無的,中國人算什麼?東亞病夫,你有什麼了不起。人家可能不屑於理你,可能對你同情一點,給你點施捨。現在不一樣了,現在你是大戶,他看著你覺得嫉妒。不一樣了。

問:“紅二代”之間,有沒有這樣的習慣,就是對當政的“紅二代”領導人進言,就國家大事提提意見?

答:我不知道別人怎麼樣,我一般沒有。為什麼呢?如果他當了官,你講話他愛不愛聽,這是第一;另外,好不容易聚到一塊,對他是個放鬆的機會,你給他提個問題,幹嘛呢?人家本來跟我們聚一塊,是聊聊天,回憶過去,對他來講是放鬆。官場那麼緊張,你突然說你這事做的不對,至少我不會這麼說,除非他提出來,要聽我的意見。我從來不寫信,我要寫就寫公開信,交給誰都不好。

午餐臨近尾聲。

我問小魯,現在閒下來了,做些什麼?他說,他和太太(粟裕將軍的女兒)經常出國旅遊,已經走過了104個國家與地區。每年外出旅遊平均一百天。在提到台灣、香港、澳門時,他都特別在每個地名後加上“地區”兩個字。陳毅當過近10年的中國外長,小魯是武官出身,這些國家利益的細節表述至關重要。

他送我厚厚一冊他編輯的陳毅影集,書名是他父親的一句詩:“真紅不枯槁”。我們移到大餐桌的另一半。小魯借了一台會所的手提電腦,讓我看看“道歉會”當天的照片。因不是他所熟悉的電腦,照片在屏幕上頻頻跳脫,他焦急起來。他指著照片上一位年逾古稀的女老師說,道歉會上,是她站起來,向我鞠躬,謝謝我在文革時保護了她。

餐桌上,還留下不少菜。這是中國常見的情景。想起近來習總書記與中央政府倡導節儉,頗有些內疚。與陳小魯道別時,他正坐在餐桌的手提電腦前,專心地查找什麼文件。他抬了抬頭,與見面時一樣,沒有客套,匆匆作別。

走出會所,午後的秋陽,有些蕭瑟,門前的街道亮堂精幹了些。八中校門口,兩位管停車的老大媽,扎著紅袖章,正在值勤;校門口,一位穿著準警察制服的年輕保安也在值勤。他們都在維持各自的秩序。

47年前,20歲的陳小魯就是在這裡走向一場瘋狂而殘酷的血色革命。這頓午餐,就像是他邀我直面一位無情的歷史證人。街對面的八中,咫尺天涯,是伴隨他一生、無法逃避的十字架。這條十字架,陳小魯扛得很累,有些是父輩的紅色遺業,有些是自身悔悟反思,同道與叛逆,理想與矛盾,難斷是非。

------

慶宣和會所,北京

刺身三文魚

巧拌月芽骨

鄉巴佬豆干

衝浪話梅參2份

剁椒小黃魚2份

絲瓜炒蝦仁

小炒驢肉

清炒雞毛菜

果盤2份

刀削麵2份

美點雙拼

藍莓1瓶

528元人民幣/位

資料圖:“文革”結束後,陳小魯等校友在八中的校慶活動中與老師握手

資料圖:“文革”結束後,陳小魯等校友在八中的校慶活動中與老師握手A Leader in Mao's Cultural Revolution Faces His Past - NYTimes.com

mobile.nytimes.com/.../a-student-leader-in-maos-cultural-revolution.html...

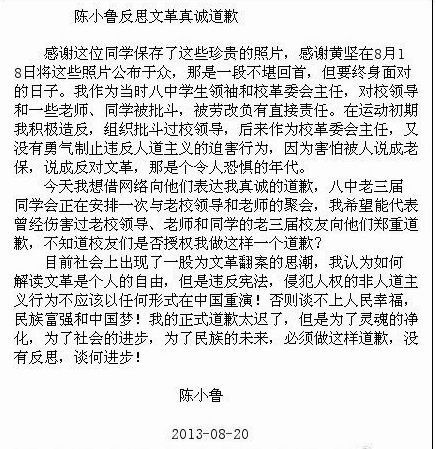

陈晓鲁君反思文革并真诚道歉

本月20日,本博转贴一位老红卫兵关于1966年北京八中文革运动对教师批斗的图文(标题:迟来47年的道歉)。文中提到陈毅元帅之子陈晓鲁(老何老友)。

陈毅元帅:

陳毅之子陳曉魯憶童年

http://news.sina.com 2011年06月29日 01:40 僑報

不知道父親是做什麼的

我四歲的時候,家搬到了上海,我被送進宋慶齡辦的中國福利基金會的幼兒園。那時我的脾氣很倔,不願去幼兒園。不管大人用什麼辦法,我就是不吃飯,又哭又鬧,居然在幼兒園絶食了三天。最後,幼兒園把我退回去了。

那時我家住在上海興國路的一座小樓,現在好像是家賓館。我印象中,父親很忙不太管我。我早上經常不起床,有時到中午吃飯都不起床。有一天,他不 知道因為什麼發脾氣,吃中飯時又聽說我還沒起床呢,一下就急了。他衝上樓說:“養這孩子有什麼用啊 ”抱起我,就要往樓下扔。當時不僅把秘書們都嚇壞了,也真就把我睡懶覺的毛病治好了。

我家是1955年搬到北京的,先住在東交民巷新八號,在那裏和羅榮桓、賀龍、張鼎丞住鄰居。我起初上的是北京育英學校,大家都住校。我感到和同 學們一起玩,特別痛快,特別是星期天。從星期一到星期六,都有生活老師管。父母在外地工作的同學大概十幾個人,星期天阿姨放假,他們就撒歡兒了。我小時候 雖然不願意上幼兒園,但這時我卻特別喜歡住校,星期六也不願回家,周末整個校園就成了我們這些不回家學生的天下了。

有一次,我有一個月都沒回家。母親不高興了,說:這孩子怎麼老不回家呀 這不行。在育英上了一年之後,母親就把我轉到北京第一實驗小學走讀。

在育英學校時,人家問:“你爸是幹什麼的 ”我只知道我爸叫陳毅,真不知道他幹什麼的。到了實驗一小,同學們有的說,我爸爸是司令,他爸爸是部長。在家裏,父母從不跟我們講什麼職務、級別這些事 兒。我就覺得他也是個“幹部”吧,在政府工作。後來我是從報紙上看到父親是外交部長、副總理,是個大幹部。我記得很清楚,在第一實驗小學畢業時填表,班主 任才知道我是陳毅的兒子。他說:“哎呀,我根本沒想到,你是陳老總的兒子呀!”

在中南海泳池可以見到毛澤東

1958年,我家搬到了“海里”(指中南海)。我們家是在懷仁堂西側的一個夾道內,這裏據說原來是宦官還是宮女住的,叫慶雲堂。這個夾道內有四 家:第一家是李富春,他家門的朝向和懷仁堂平行,那個院是標準的四合院,差不多有十來間房子,大約八百平方米。正房有七間,比較寬,側房也有個五間吧。他 家側面是個夾道,我們都走這個夾道。這個夾道第二家是側面開門,是譚震林家。第三家就是鄧小平家,第四家是我們家。我們這四家住得比較近。懷仁堂後邊原來 是林伯渠住,懷仁堂的東側是董必武、陳伯達家。

中南海里面分三個區,我們住的這片叫乙區,然後走西門。甲區是毛主席、楊尚昆他們住,中央辦公廳在甲區,劉少奇原來也在甲區住。甲區和乙區之間是有崗哨的,好像是甲區可以到乙區,乙區可以到丙區。乙區到甲區要經過登記手續。

中南海有兩個游泳池,據說是毛主席用《毛澤東選集》的稿費修的,一個室內的和一個室外的。丙區是國務院機關,周恩來的西花廳在丙區,還有普通幹部住在裏面,文化革命中就全給清出去了。

那時候中南海很熱鬧,夏天的環境很好,可以划船,可以游泳。一般人中午12點以後可以去游泳,游到一點半就離開,因為兩點鐘要上班。毛主席在北 京時,一點半後肯定來游泳。他有一個專用的更衣棚子。換了衣服,就下水游泳。一些小一點的孩子們一點半上來以後,換衣服的時候就故意磨蹭,這樣就可以見到 毛主席了。毛主席看到這些小孩子們,有時就會招呼:“你們都來游啊!”毛主席說了,誰還敢管 小孩們喊着,“毛爺爺好!”就紛紛跳下水。那時我年紀稍大一點了,比較自覺,不會這樣做。冬天,中海結冰了,會鋪溜冰場,有人管理,就在離北海大橋不遠的 地方,我們就在上面滑。

看電影風波與“規矩”

丙區有個紫光閣,邊上是國務院小禮堂,經常放電影。原來放電影,一是甲區有個電影廳,給主席看,有時候我們也去看。後來我們主要是在國務院小禮 堂看電影,比如像《冰山上來客》等我都是在那裏看的。當時童小鵬也住中南海,他不但愛攝影,自己還有個小的8毫米電影放映機。他有些二戰的片子,二戰那個 大海戰等,他有時也放電影。國務院小禮堂看電影要買票,一般都是外邊公演的。偶爾放一些內部電影,但不讓我們小孩看。門口會掛個小黑板,只準成年人看,小 孩不得入內,那就屬於內部電影了。我們看到那個牌子就自覺不去了。有次,童小鵬的兒子不滿意了,他就自己寫個牌子:今日電影大人不准入內。好多幹部都在 看,怎麼回事啊 就是他在那放他的小電影,不准大人入內。

住到“海里”以後,有時就能見到毛主席了,但大多是離得遠遠的。因為中南海里有規矩,孩子們不能幹擾領導人的工作。當時就是遇到劉少奇、周恩來 這些領導人,這種場合我一般也都不問不說,規矩挺大的。中南海的生活環境一開始還比較寬鬆,有些院裡的孩子,可以帶同學進海里來玩,登記一下就行。但我們 家的孩子都沒有,因為父母交待了,覺得是中央重地嘛,所以我從來沒有帶任何同學進去。

當然住中南海里面各家的孩子經常是串來串去的,這個人家也不管。孩子們相處得都還可以,一般不怎麼打架,比較和諧。那裏的生活就是大人管大人,小孩自己管自己。原來呢,領導人之間也還互相往來,後來共産黨內部情況也是有點緊張,就不太往來了。

A Leader in Mao’s Cultural Revolution Faces His Past

“I

was too scared. I couldn’t stop it. I was afraid of being called a

counterrevolutionary, of having to wear a dunce’s hat.” CHEN XIAOLU

Gilles Sabrie for The New York Times

By JANE PERLEZ

December 6, 2013

BEIJING — ON the surface, at least, there is not much about Chen Xiaolu to suggest a lifetime of regret.

The son of one of Communist China’s founding generals, he enjoyed privilege at an early age and then a career as a business consultant that took him around the world. Now 67, he relaxes on golf courses in Scotland and southern France and eschews the dark suits and high-maintenance black hair of most affluent Chinese men for casual shirts and a gray buzz cut.

But beneath the genial exterior is a memory that has haunted him for nearly 50 years. There he was, back in high school, a fresh-faced member of the volleyball team and a student leader in Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution, ordering teachers to line up in the auditorium, dunce caps on their bowed heads. He stood there, excited and proud, as thousands of students howled abuse at the teachers.

Then, suddenly, a posse stormed the stage and beat them until they crumpled to the floor, blood oozing from their heads. He did not object. He simply fled. “I was too scared,” he recalled recently in one of several interviews at a restaurant near Tiananmen Square, not far from his alma mater, No. 8 Middle School, which catered to the children of the Mao elite. “I couldn’t stop it. I was afraid of being called a counterrevolutionary, of having to wear a dunce’s hat.”

A ripple of confessions about the Cultural Revolution from former Red Guards, most of them retired men of modest backgrounds, has surfaced in the last few months. But it was Mr. Chen’s decision to step forward in August with a public apology that has drawn the most attention, raising hopes that a nation so determined to define its future might finally be moving to confront the horrors of its past.

He did so, he said, not only for personal redemption but also for profound reasons to do with China’s political development that must include the rule of law.

“Many people are thinking back fondly to the good old days of the Cultural Revolution, and are saying it was just against corrupt officials,” he said in an interview. “But many things happened in the Cultural Revolution that violated people’s rights. The majority in China did not really experience the Cultural Revolution, and those of us who did have to tell people about it.”

Mr. Chen’s remorse stands out because of his stature, then and now. He is quite candid that as the son of Chen Yi, a founder of Communist China and its longtime foreign minister, he was handed the mantle of immense authority during the decisive, early days of the Cultural Revolution.

“I bear direct responsibility for the denouncing and criticism, and forced-labor re-education of school leaders, and some teachers and students,” Mr. Chen wrote in a blog post on his school alumni website in August that quickly circulated on the Internet. “I actively rebelled and organized the denouncements of school leaders. Later on when I served as the director of the school’s Revolution Committee, I wasn’t brave enough to stop the inhumane prosecutions.”

“My official apology comes too late, but for the purification of the soul, the progress of society and the future of the nation, one must make this kind of apology,” he concluded.

The apology has drawn a mixed response. Slightly more than half of the comments on the alumni website commended him. On Chinese websites, many questioned why it was necessary to pick over old wounds.

THE Cultural Revolution remains largely hidden from view in China as successive governments have discouraged discussion of the turmoil and terror that Mao orchestrated to perpetuate his rule but that almost brought the country to its knees.

Deng Xiaoping repudiated the Cultural Revolution in 1978, and the party has acknowledged it was a mistake, but a full accounting has never occurred.

A particularly delicate subject for the party has been the number of people killed.

In Beijing alone, about 1,800 people died during August and September 1966, the height of the frenzy, when Mao first deployed students as Red Guards to turn against the party, according to the historians Roderick MacFarquhar and Michael Schoenhals. Estimates range from 1.5 million to three million dead across China from 1966 to 1976.

A Chinese historian of the Cultural Revolution, Xu Youyu, described Mr. Chen’s apology as “very unusual” because former Red Guards — an entire generation of Chinese now in their 60s — generally justify their actions during the Cultural Revolution and prefer to emphasize their role as victims rather than perpetrators; they rarely apologize in private, much less in public.

The fateful criticism ceremony of teachers at the Zhongshan Concert Hall, near the Forbidden City, that Mr. Chen organized was brutal even before it began, said Huang Jian, the chairman of the alumni group.

On the way to the auditorium, students “wielded whips,” lashing at the school principal, Wen Hanjiang, as they frog-marched him, Mr. Huang said. Mr. Wen, now 89 and living in Beijing, where Mr. Chen recently visited him, was beaten on the stage, too.

Back at the school, the atmosphere darkened. The school’s senior party official, Hua Jia, committed suicide. She took her life after two weeks of beatings and being fed only bits of food in a storeroom where she was imprisoned, Mr. Chen said.

Someone told him of the suicide, and he rushed to the room to find the body on the floor.

“She used a string tied to the windowsill, put her head through the noose and then knelt down to hang herself,” he said. Mr. Chen offered the details quickly and quietly, a tinge of embarrassment in his words. It turned out, he said, she had been a loyal member of the Communist Party for 30 years.

During the early turmoil, Mr. Chen lived at home with his parents at Zhongnanhai, the sprawling compound in the center of Beijing where senior party officials were assigned traditional courtyard-style houses and luxuries existed unknown beyond the high walls.

His father insisted that the family could not discuss the Cultural Revolution at home, he said. “To put it simply, my father said you must participate in the Cultural Revolution but be careful and prudent.”

They maintained a “Chinese screen” of silence about the violence, he said. “I never told my father anything about the suicide” of Ms. Hua, he said. “My father knew someone could use me to target him.”

LIFE was easy at Zhongnanhai. The children were often summoned to watch Mao swim in one of two 50-meter pools — outdoors in summer, indoors in winter. There were basketball games, rowing on a lake and weekend movies.

But soon, trouble struck at the heart of the Chen family. In a speech in early 1967, Chen Yi dared to criticize the Cultural Revolution. Mao sidelined him, and the man who had greeted every foreign leader to the new China was subjected to a humiliating self-criticism session and ordered to stay at home.

After his father was disgraced, Mr. Chen stopped living at home “to keep more distance.” In the summer of 1968, Mao dispersed the students to the countryside. Prime Minister Zhou Enlai spared Mr. Chen that fate by sending him to the army.

In 1972, Chen Yi died of colon cancer, a broken man. Chen Xiaolu came home from the army for the funeral. Out of the blue, he said, Mao turned up dressed in pajamas and a winter topcoat to pay respects to his father. In front of the Chen family, Mao reinstated Chen Yi in the pantheon of revolutionary greats by calling him a “good comrade.”

That afternoon, Mr. Chen drank beer with a school friend, Ji Sanmeng, and shared a poem, Mr. Ji recalled, about how his father, a hero, had endured ill treatment for the past five years at the hands of Mao and his men.

By then, Mr. Chen’s faith in Mao had evaporated, although he never said so publicly.

Bree Feng contributed research.

The son of one of Communist China’s founding generals, he enjoyed privilege at an early age and then a career as a business consultant that took him around the world. Now 67, he relaxes on golf courses in Scotland and southern France and eschews the dark suits and high-maintenance black hair of most affluent Chinese men for casual shirts and a gray buzz cut.

But beneath the genial exterior is a memory that has haunted him for nearly 50 years. There he was, back in high school, a fresh-faced member of the volleyball team and a student leader in Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution, ordering teachers to line up in the auditorium, dunce caps on their bowed heads. He stood there, excited and proud, as thousands of students howled abuse at the teachers.

Then, suddenly, a posse stormed the stage and beat them until they crumpled to the floor, blood oozing from their heads. He did not object. He simply fled. “I was too scared,” he recalled recently in one of several interviews at a restaurant near Tiananmen Square, not far from his alma mater, No. 8 Middle School, which catered to the children of the Mao elite. “I couldn’t stop it. I was afraid of being called a counterrevolutionary, of having to wear a dunce’s hat.”

A ripple of confessions about the Cultural Revolution from former Red Guards, most of them retired men of modest backgrounds, has surfaced in the last few months. But it was Mr. Chen’s decision to step forward in August with a public apology that has drawn the most attention, raising hopes that a nation so determined to define its future might finally be moving to confront the horrors of its past.

He did so, he said, not only for personal redemption but also for profound reasons to do with China’s political development that must include the rule of law.

“Many people are thinking back fondly to the good old days of the Cultural Revolution, and are saying it was just against corrupt officials,” he said in an interview. “But many things happened in the Cultural Revolution that violated people’s rights. The majority in China did not really experience the Cultural Revolution, and those of us who did have to tell people about it.”

Mr. Chen’s remorse stands out because of his stature, then and now. He is quite candid that as the son of Chen Yi, a founder of Communist China and its longtime foreign minister, he was handed the mantle of immense authority during the decisive, early days of the Cultural Revolution.

“I bear direct responsibility for the denouncing and criticism, and forced-labor re-education of school leaders, and some teachers and students,” Mr. Chen wrote in a blog post on his school alumni website in August that quickly circulated on the Internet. “I actively rebelled and organized the denouncements of school leaders. Later on when I served as the director of the school’s Revolution Committee, I wasn’t brave enough to stop the inhumane prosecutions.”

“My official apology comes too late, but for the purification of the soul, the progress of society and the future of the nation, one must make this kind of apology,” he concluded.

The apology has drawn a mixed response. Slightly more than half of the comments on the alumni website commended him. On Chinese websites, many questioned why it was necessary to pick over old wounds.

THE Cultural Revolution remains largely hidden from view in China as successive governments have discouraged discussion of the turmoil and terror that Mao orchestrated to perpetuate his rule but that almost brought the country to its knees.

Deng Xiaoping repudiated the Cultural Revolution in 1978, and the party has acknowledged it was a mistake, but a full accounting has never occurred.

A particularly delicate subject for the party has been the number of people killed.

In Beijing alone, about 1,800 people died during August and September 1966, the height of the frenzy, when Mao first deployed students as Red Guards to turn against the party, according to the historians Roderick MacFarquhar and Michael Schoenhals. Estimates range from 1.5 million to three million dead across China from 1966 to 1976.

A Chinese historian of the Cultural Revolution, Xu Youyu, described Mr. Chen’s apology as “very unusual” because former Red Guards — an entire generation of Chinese now in their 60s — generally justify their actions during the Cultural Revolution and prefer to emphasize their role as victims rather than perpetrators; they rarely apologize in private, much less in public.

The fateful criticism ceremony of teachers at the Zhongshan Concert Hall, near the Forbidden City, that Mr. Chen organized was brutal even before it began, said Huang Jian, the chairman of the alumni group.

On the way to the auditorium, students “wielded whips,” lashing at the school principal, Wen Hanjiang, as they frog-marched him, Mr. Huang said. Mr. Wen, now 89 and living in Beijing, where Mr. Chen recently visited him, was beaten on the stage, too.

Back at the school, the atmosphere darkened. The school’s senior party official, Hua Jia, committed suicide. She took her life after two weeks of beatings and being fed only bits of food in a storeroom where she was imprisoned, Mr. Chen said.

Someone told him of the suicide, and he rushed to the room to find the body on the floor.

“She used a string tied to the windowsill, put her head through the noose and then knelt down to hang herself,” he said. Mr. Chen offered the details quickly and quietly, a tinge of embarrassment in his words. It turned out, he said, she had been a loyal member of the Communist Party for 30 years.

During the early turmoil, Mr. Chen lived at home with his parents at Zhongnanhai, the sprawling compound in the center of Beijing where senior party officials were assigned traditional courtyard-style houses and luxuries existed unknown beyond the high walls.

His father insisted that the family could not discuss the Cultural Revolution at home, he said. “To put it simply, my father said you must participate in the Cultural Revolution but be careful and prudent.”

They maintained a “Chinese screen” of silence about the violence, he said. “I never told my father anything about the suicide” of Ms. Hua, he said. “My father knew someone could use me to target him.”

LIFE was easy at Zhongnanhai. The children were often summoned to watch Mao swim in one of two 50-meter pools — outdoors in summer, indoors in winter. There were basketball games, rowing on a lake and weekend movies.

But soon, trouble struck at the heart of the Chen family. In a speech in early 1967, Chen Yi dared to criticize the Cultural Revolution. Mao sidelined him, and the man who had greeted every foreign leader to the new China was subjected to a humiliating self-criticism session and ordered to stay at home.

After his father was disgraced, Mr. Chen stopped living at home “to keep more distance.” In the summer of 1968, Mao dispersed the students to the countryside. Prime Minister Zhou Enlai spared Mr. Chen that fate by sending him to the army.

In 1972, Chen Yi died of colon cancer, a broken man. Chen Xiaolu came home from the army for the funeral. Out of the blue, he said, Mao turned up dressed in pajamas and a winter topcoat to pay respects to his father. In front of the Chen family, Mao reinstated Chen Yi in the pantheon of revolutionary greats by calling him a “good comrade.”

That afternoon, Mr. Chen drank beer with a school friend, Ji Sanmeng, and shared a poem, Mr. Ji recalled, about how his father, a hero, had endured ill treatment for the past five years at the hands of Mao and his men.

By then, Mr. Chen’s faith in Mao had evaporated, although he never said so publicly.

Bree Feng contributed research.

沒有留言:

張貼留言