-----

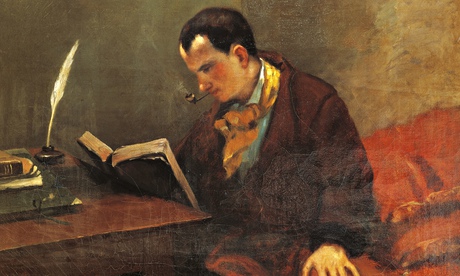

“Genius is nothing more nor less than childhood recaptured at will.”— Charles Baudelaire

Baudelaire dismissed Victor Hugo as 'an idiot' in unseen letter

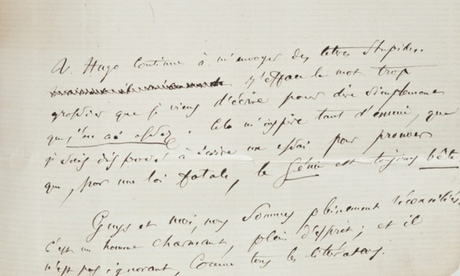

Detail from Baudelaire's letter, containing his private opinion of the 'stupid' Les Misérables author. Photograph: Christie's

Detail from Baudelaire's letter, containing his private opinion of the 'stupid' Les Misérables author. Photograph: Christie's The first edition of Les Fleurs du Mal, tooled in gold and silver, colored inlays of flowers and symbols of death and evil, similiarly tooled. Photograph: Christie's

The first edition of Les Fleurs du Mal, tooled in gold and silver, colored inlays of flowers and symbols of death and evil, similiarly tooled. Photograph: Christie's

蒂永維爾(法語:Thionville,法語發音:[tjɔ̃vil] ⓘ),法國東北部城市,大東部大區摩澤爾省的一個市鎮,同時也是該省的一個副省會,下轄蒂永維爾區[1],其市鎮面積為49.86平方公里,2022年1月1日時人口數量為42,778人[2],是摩澤爾省人口第二多的市鎮,僅次於省會梅斯,在法國城市中排名第187位。

蒂永維爾位於摩澤爾省西北部,摩澤爾河左岸,靠近盧森堡、德國以及比利時邊境,歷史上為重要的邊防城市,其市區內有多處軍事歷史遺蹟,近代則因鋼鐵和煤炭開採而獲得發展,現代為洛林歐洲城市帶上的重要節點[3]。

ictor

Hugo was excessive, in life as in literature. Cocteau said that ‘Victor Hugo was a madman who thought he was Victor Hugo.’ The critic and gardener Alphonse Karr wondered: ‘What was the point of going to all the trouble of becoming Victor Hugo?’ His English biographer, Graham Robb, wrote that Hugo’s life was ‘an inspiring lesson in the art of surviving one’s own personality’. Hugo even entered the Guinness Book of Records for having written (in Les Misérables) the longest sentence in literature before Proust came along. When Hugo indulged in table-turning, only the greatest emerged from the shadows: Dante, Napoleon, Socrates and Mozart; Hannibal spoke to him in Latin, while Shakespeare dictated a whole comedy, usefully in French. His vanity was often preposterous. In 1873 the 71-year-old genius was busy seducing his new maid, Blanche; when she touched his penis, he explained to her: ‘It’s a lyre

Astonishing Things: The Drawings of Victor Hugo review – masterpieces from a man with a heart as big as the Notre Dame

Royal Academy, London

From hanged men and inky cephalopods to shadowy gothic castles, these cosmic, horror-tinged works let the Les Misérables writer and liberal political campaigner speak directly to us

Victor Hugo is the French equivalent of Shakespeare and Dickens. The inventor of Quasimodo and Jean Valjean is so universal that we absorb his myths even if we have never picked up one of his books. Yet how much do most of us know about Hugo himself, behind the books, the films, the musicals? By dedicating an exhibition to this versatile creator’s visual art, which started with a few caricatures and developed into sublime and surreal masterpieces, the Royal Academy does something unexpectedly moving. It takes you into the secret heart of a man we tend to think of only as a classic.

For instance we discover that Hugo campaigned against the death penalty nearly two centuries ago. His 1854 drawing Ecce Lex (Behold the Law) is a macabre inky portrait of a hanged corpse, part of his doomed campaign to save a condemned murderer called John Tapner. Hugo opposed capital punishment on principle, but a few years later gave permission for this drawing to be made into a print protesting the execution of American anti-slavery activist John Brown. If there was a liberal cause, Hugo threw his huge heart into it.

One of the first drawings you encounter in this sensitively curated show is his sketch of the council chamber in the town hall of Thionville in the north-east of France, after it was left in ruins by the invading Prussian army in 1871. Thus, in his late 60s, he added war artist to his vocations of author and campaigner, and recorded the violence of the Franco-Prussian war. In fact, this disaster for France improved his own life. It led to the fall of the dictator Louis Napoleon, whom Hugo had defied, choosing political exile on Guernsey, where he created some of his most haunting art.

That was his public life. Hugo’s art, however, takes you under his skin, without rules or any audience except himself, absolutely free and dauntingly creative. You can feel the isolation and soul-searching in his 1850 sketch Causeway, which dwells on nothing more than a bleak rocky causeway, perhaps his road to exile. In a drawing beside it he ponders the woody morass of a soaking breakwater in Jersey – the first Channel Island to which he fled.

Sketch? Drawing? It’s hard to define exactly what these are. Hugo uses a mixture of ink, charcoal, graphite and wash to create his murky paper visions. Sometimes he works on a tiny scale: The Abandoned Park, a silhouette-like image of trees beside a mirroring lake, is just 4.4cm tall and 3.5cm across. The miniaturisation adds to the ghostliness. Yet he can also take drawing to staggering largeness, as in the final depiction of a Guernsey lighthouse with a frail staircase spiralling up to a mystical, hopeful light.

At times Hugo is just the writer doodling – using up spare ink, he said – yet his doodles develop. A symmetrical ink stain, like a Rorschach blot, has little faces drawn into it. Other frolics that Hugo called “taches”, or stains, are boldly abstract. Sometimes they form themselves into cosmic visions of planets or unreal landscapes but others remain free and formless.

Out of this wild freedom a theme emerges: architecture. This should not be a surprise because after all the real hero of his novel Notre-Dame de Paris is not Quasimodo but Notre-Dame itself – a tottering, unloved old pile of stone when Hugo wrote it. So as well as Dickens, he resembles those Victorian champions of the gothic Ruskin and Pugin. But he’s Ruskin on a lot of beaujolais, his imagination drunk on gothic turrets and spires; castles on hilltops or by lakes; fairytale castles and nightmare castles; real ones and dreamed ones.

When he visited the town of Vianden, in today’s Luxembourg, its castle fascinated him so much he lived in it for three months. He depicts it as shadowy and unreal, like a design for a 30s horror movie. In a second drawing the castle is a floating phantasm above a rickety array of wooden houses: not so much Dracula’s castle as Kafka’s.

When Hugo lived on Guernsey he turned his house into a gothic retreat with a Romantic interior full of fantastical touches. It is evoked here with spooky photographs and a battered mirror whose wooden frame he painted with colourful birds. His fireplace, which he sketched, was emblazoned with a huge H, as if he were a medieval lord.

It’s estimated that Hugo made 4000 drawings, of which about 3000 survive; 77 are shown in Astonishing Things: The Drawings of Victor Hugo (until 29 June). This is one of the brownest exhibitions I’ve ever seen: brown ink, brown wash, brown pencil, occasionally lightened by black. Even when Hugo’s own work is interrupted by the dozen albumen prints of Hauteville House (his place of exile on Guernsey), the colour remains entirely consonant with the rest of the show. Which means that when, occasionally, Hugo decides to add a patch of colour, it blazes out with twice its normal effect. Meeting Room of the Municipal Council of Thionville, after the Entry of the Prussians shows the interior of a wrecked building. Through the blown-out windows can be seen a sky which is not the usual brown but actually light blue. Somehow this registers not so much as authentic but as shockingly original. The wall labels announce the conventional media – charcoal, graphite, ink, gouache, crayon and gum – which Hugo used. But there were also some more unconventional ones, what Robb calls ‘a whole pantry of other substances: blackberry juice, caramelised onion, burned paper, soot from the lamp and toothpaste

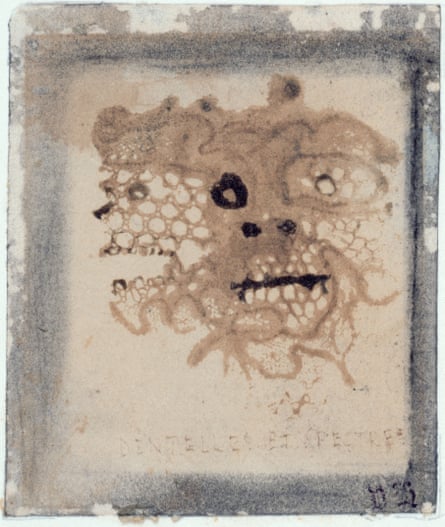

Henry James thought the weakness of Roman civilisation was that it was only good at doing large things; he judged the Pont du Gard stupid, adding: ‘The Roman rigidity was apt to overshoot the mark, and I suppose a race which could do nothing small is as defective as a race that can do nothing great.’ One of the joys of this show is that Hugo, author of vast fictions and prolonged poems, was also very good at doing small, even very small, things. He can concentrate a whole abandoned park into a space four and a half by three and a half centimetres. Lace and Spectres (c.1855-56) is almost as tiny, but its two Japanese-style death’s heads (or perhaps the same head shown in full face and profile) roar out at you like the biggest fiends from Hell. The show engulfs you in Hugo, and very rarely reminds you of other artists. Ink-blackened Page with Half-moon and Fingerprints, a view upwards from the interior of a well with human heads (made up of the artist’s fingerprints) peering down, echoes Goya. But the only time I felt the strong presence of another artist, it was not imitative but proleptic. Planet-Eye (c.1854), a vast eyeball floating in cosmic clouds, sharply anticipates Odilon Redon’s Oeil-Ballon by 25 years. Redon’s noirs were to inhabit a parallel psychic zone, full of eyes floating in monochrome skies, grinning spiders and crackly skeletons.

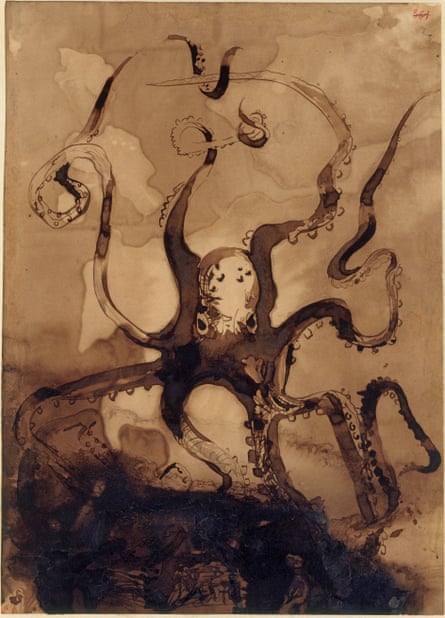

These drawings are the negative image of Hugo’s vastly populated fiction. Here human life is barely in evidence. We are presented instead with landscapes which are not topographical, seascapes where there are no calm waters, with ruined buildings, castles both fantastical and destroyed, plus menacing cliffs, towering clouds, bleak fortresses, dead cities and blasted heaths. So, as with those sparse irruptions of colour, when we come across a drawing called The Cheerful Castle it feels like a blasphemy against normality. And it is a relief to get back to The Shade of the Manchineel Tree, that infamous West Indian growth whose sap and fruit are poisonous, and whose very shade is toxic. This is a world in which terrifying serpents and octopuses writhe, while a fat spider lords it menacingly over a town; here a causeway seems to lead nowhere, there a breakwater rears in panic, while ships are broken, dismasted and adrift. The sun fails to shine on landscapes whose mood is encapsulated by the title of one: Twilight, stubborn, black, hideous. These bleak visions become the bleaker for their oppressive lack of any human presence. The boats are unmanned, the cities unpeopled, the lighthouse lacks a lighthouseman, the pastures are absent of peasants and even animals. There are only three human figures – two of them hanged men; there is a stone angel and a statue of the crucified Christ. That manchineel tree casts a shadow in the shape of a human skull, while grotesque faces loom from cliffs and from the stalk of the vast threatening fantasy of Mushroom. In The Dream a sleeper’s tortured hand reaches out fearfully to ward off a floating, indecipherable face half-hidden by clouds.

You have to wrench yourself back into remembering that ordinarily Hugo’s world view was progressive, humanistic and cheerful. He looked forward to a time of universal fraternity. ‘In the 20th century,’ he once prophesied, ‘war will be dead; the scaffold will be dead, animosity will be dead, royalty will be dead; but Man will live.’ Which scores precisely nought out of four on what George H.W. Bush famously called ‘the vision thing’.

沒有留言:

張貼留言