Rebel architects: building a better world

Working on the fringes of the law, rebel architects are trying to improve people’s lives in tough areas. From floating homes to disaster-proof houses and bamboo domes, Aaron Millar meets the men and women building for their communities

Buildings affect us. They reflect our cultural values and mould our behaviour. “We shape our dwellings,” Winston Churchill said, “and afterwards our dwellings shape us.” Yet in recent times appearance has been admired over purpose, aesthetics over social need.

That may be set to change. Santiago Cirugeda, a subversive architect from Seville, has shunned the glamour, and financial security, of luxury office space for the architecture of activism. In austerity-hit Spain, 500,000 new buildings lie derelict, unemployment is high and funding for community initiatives is minimal. Pulling these threads together, Cirugeda and his team – often working on the fringes of the law – use rapid building techniques, recycled materials and volunteer labour on abandoned municipal land for projects that people need.

In the waterside slums of Port Harcourt, Nigeria, 480,000 residents face the threat of displacement as the government seeks to redevelop their land, claiming urban renewal is necessary for economic development. But Kunlé Adeyemi has an alternative solution. He envisages a city of floating homes that would allow residents to remain within their community, and safe from rising tides, while at the same time improving the quality of their lives.

In Pakistan, Yasmeen Lari is applying skills learned building vast commercial structures and restoring historic national monuments to help communities at risk from flood and earthquake damage. She has built more than 36,000 safe homes and won the UN Recognition Award in the process.

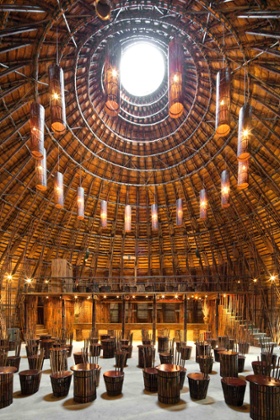

But perhaps most striking of all are the buildings of the Vietnamese architect Vo Trong Nghia. Since the economic boom of the 2000s, population – and pollution – in the country has soared. Only 2.5% of Ho Chi Minh City is “green space” and nine in 10 children under five suffer respiratory illness. Nghia is combatting these problems with green architecture: buildings infused with living plants and trees. “Vietnamese cities have lost their tropical beauty,” he says. “For a modern architect the most important mission is to bring green spaces back.”

Rebel Architects, a six-part series, premieres on Al Jazeera on 18 August (aljazeera.com/rebelarchitects)

沒有留言:

張貼留言