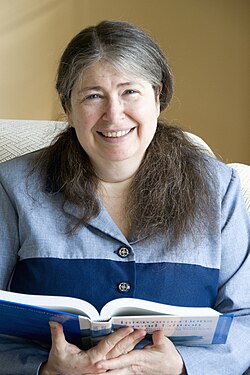

Radia Perlman | |

|---|---|

Perlman in 2009 | |

| Born | December 18, 1951 |

| Alma mater | MIT |

| Known for | Network and security protocols; computer books |

| Awards | Internet Hall of Fame National Inventors Hall of Fame |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Computer Science |

| Institutions | Intel |

| Thesis | Network layer protocols with Byzantine robustness (1988) |

| Doctoral advisor | David D. Clark |

Every time you send an email, stream a video, or load a webpage—you're using technology she invented. And you probably don't know her name.

Computer networks were growing. Companies wanted to connect hundreds, eventually thousands of computers together. But there was a fundamental issue: network loops.

Imagine data packets as cars on a road. Now imagine that road has no exit signs, no GPS, no way to know which turn leads where. Cars would just drive in circles forever, creating massive traffic jams that crash the entire system.

That's what was happening in early computer networks. Data would get trapped in loops, circling endlessly, multiplying with each pass, until the network was so overwhelmed it crashed completely. These were called "broadcast storms"—cascading failures that could take down entire corporate networks in seconds.

Engineers knew this was a problem. They'd tried various solutions. Nothing worked reliably.

Radia Perlman figured it out.

She created the Spanning Tree Protocol (STP)—an algorithm that automatically detects and prevents network loops. It does this by mathematically organizing network connections into a tree structure (no loops by definition), while maintaining backup paths in case primary connections fail.

It sounds simple when you summarize it. It wasn't.

The algorithm had to work automatically, without human intervention. It had to handle networks of any size. It had to recover instantly when connections failed. It had to be efficient enough not to slow down data transmission.

Perlman solved all of it.

STP became standardized (IEEE 802.1D) and implemented in nearly every network switch and bridge manufactured since. It's invisible to users—which means it's working perfectly. Every time your data travels across complex networks without getting stuck in loops, that's Radia Perlman's invention protecting you from chaos.

The internet, as we know it—with billions of devices connected through countless redundant paths—fundamentally relies on this technology.

Radia Perlman made it possible.

But when people talk about who "invented the internet," her name rarely comes up.

Instead, we hear about Vint Cerf and Bob Kahn—the "fathers of the internet" who developed TCP/IP, the communication protocols that let computers talk to each other. Their work was crucial. They deservedly received recognition, awards, honors.

But TCP/IP doesn't work without the underlying network architecture that STP enables. You can't have the internet without both.

Yet only the men became famous.

This pattern repeats constantly in tech history. Men who make important contributions become legends. Women who make equally important contributions become footnotes—if they're mentioned at all.

And the excuses are always the same: "Maybe she just didn't promote herself enough." "Maybe her work wasn't as significant." "Maybe it's just coincidence."

It's not coincidence.

Radia Perlman has a PhD from MIT. She's invented numerous other protocols and technologies beyond STP. She's worked at some of the most prestigious tech companies in the world. She's published over 100 papers. She literally wrote the textbook on network design—Interconnections: Bridges, Routers, Switches, and Internetworking Protocols is used in computer science programs worldwide.

She even wrote a poem about STP called "Algorhyme":

"I think that I shall never see

A graph more lovely than a tree.

A tree whose crucial property

Is loop-free connectivity..."

She's brilliant, accomplished, and foundational to modern networking.

And most people have never heard of her.

When journalists started calling her the "Mother of the Internet" in recent years, Perlman herself pushed back. She found the title reductive—as if her contribution could be summarized with a cute maternal metaphor, as if she needed a gendered counterpart to the "fathers of the internet."

She's right. The title is limiting. But the fact that we need to debate what to call her contributions shows the problem: we have no standard narrative for women's achievements in tech because we've spent decades not telling their stories.

Perlman has never complained publicly about the lack of recognition. In interviews, she's matter-of-fact: she solved problems because they were interesting. She built systems because they needed building. Recognition wasn't the goal.

But here's what that humility has cost: generations of students studying computer science who learned about Cerf and Kahn but never heard Perlman's name. Young women entering tech fields without role models because the women who came before were written out of history. A cultural narrative that says "men invent technology" because we systematically forget the women who did.

Perlman's response to being overlooked? She kept working.

She went on to develop TRILL (TRansparent Interconnection of Lots of Links), improving on her own STP design. She made major contributions to network security and routing protocols. She kept teaching, publishing, innovating.

She didn't need fame. The work was enough.

But the rest of us needed to know about her. Because every time we tell the history of technology as if only men built it, we lie. We lie to students, we lie to young engineers, we lie to ourselves about how innovation actually happens.

The truth is messier and more interesting: technology is built by teams of people—men and women—solving complex problems together. But when history is written, women's contributions disappear.

Not because they weren't there. Not because their work wasn't crucial. But because we have a cultural habit of seeing men as creators and women as helpers, even when evidence proves otherwise.

Radia Perlman didn't help build the internet. She built fundamental pieces of it. Her protocol is running on billions of devices right now. It's in your router, your workplace network, the infrastructure connecting hospitals and banks and schools.

It just works. Quietly. Efficiently. Elegantly.

Without drama.

Maybe that's why it's easy to overlook—because it works so well we don't notice it. The best technology is invisible.

But the people who create that technology shouldn't be.

In recent years, Perlman has finally received more recognition. She was inducted into the Internet Hall of Fame in 2014, the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2016. She's received major awards from professional organizations.

But these honors came decades after her most important work. She was already in her 60s when mainstream recognition arrived.

Imagine spending your entire career making foundational contributions to one of humanity's most important technologies, watching less-accomplished men receive awards and acclaim, and just... continuing to work. Because the work mattered more than the recognition.

That's not just humility. That's dedication that borders on heroic.

And it shouldn't have been necessary.

The next time you load a webpage, send a message, stream a show—remember: you're using technology that Radia Perlman invented.

The next time someone says "the internet was invented by..." and lists only male names, correct them.

The next time a young woman says she's interested in engineering but doesn't see people like her in the history books, tell her about Radia Perlman. Tell her about the woman who made the internet work, who wrote elegant algorithms that billions of people rely on daily, who proved that brilliance has nothing to do with gender.

Tell her that women have always been there, building the future, whether or not history remembered to write them down.

Radia Perlman didn't need recognition to do great work.

But we need to recognize her—because telling the truth about who built our world matters.

Because brilliance deserves acknowledgment regardless of gender.

And because every time we forget to name women's contributions, we make it harder for the next generation to believe they belong.

Radia Perlman belongs in every textbook about internet history.

And now you know why.

每次你發送電子郵件、觀看影片或載入網頁時,你都在使用她發明的技術。而你可能並不知道她的名字。

1985年,拉迪亞·珀爾曼(Radia Perlman)在數位設備公司(Digital Equipment Corporation)工作,這家公司是20世紀80年代主要的電腦公司之一。當時,她遇到了一個令網路工程師們頭痛的問題。

電腦網路正在不斷發展。公司希望將數百台,最終數千台電腦連接起來。但存在一個根本性的問題:網路環路。

想像一下,資料包就像路上的汽車。現在想像一下,這條路沒有出口指示牌,沒有GPS,也無法知道哪個轉彎通往哪裡。汽車會一直繞圈行駛,造成大規模交通堵塞,最終導致整個系統崩潰。

這就是早期電腦網路中發生的情況。資料會被困在環路中,無限循環,每次循環都會增加資料量,直到網路不堪負荷而徹底崩潰。這被稱為「廣播風暴」——級聯故障,可以在幾秒鐘內癱瘓整個企業網路。

工程師早就知道這是個問題。他們嘗試過各種解決方案,但都無濟於事。

拉迪亞·珀爾曼找到了解決辦法。

她創建了生成樹協定 (STP)——一種能夠自動偵測並防止網路環路的演算法。它透過將網路連接以數學方式組織成樹狀結構(根據定義,樹狀結構中不存在環路)來實現這一點,同時在主連接發生故障時維護備用路徑。

聽起來很簡單,但實際操作起來卻不然。

該演算法必須能夠自動運行,無需人工干預。它必須能夠處理任何規模的網路。它必須在連線發生故障時立即恢復。它必須足夠高效,不會降低資料傳輸速度。

珀爾曼解決了所有這些問題。

STP 被標準化(IEEE 802.1D),並被應用於此後生產的幾乎所有網路交換器和網橋。它對用戶來說是透明的——這意味著它運行完美。每次您的資料在複雜的網路中傳輸而不會陷入環路時,都是拉迪亞·珀爾曼的發明在保護您免受網路混亂的困擾。

我們所熟知的互聯網——數十億台設備透過無數冗餘路徑連接——從根本上依賴這項技術。

拉迪亞·珀爾曼(Radia Perlman)使這一切成為可能。

但當人們談論誰「發明了網路」時,她的名字卻鮮少被提及。

相反,我們聽到的往往是文特·瑟夫(Vint Cerf)和鮑勃·卡恩(Bob Kahn)——這兩位“互聯網之父”開發了TCP/IP協議,使計算機之間能夠相互通信。他們的工作至關重要,理應獲得認可、獎項和榮譽。

但如果沒有STP所支援的底層網路架構,TCP/IP就無法運作。沒有這兩者,就沒有網路。

然而,只有男性名聲大噪。

這種模式在科技史上不斷重演。做出重要貢獻的男性成為傳奇人物,而做出同樣重要貢獻的女性卻淪為腳註——即便她們的名字被提及,也往往被忽略。

而人們給出的理由總是千篇一律:“也許她只是沒有充分宣傳自己。”“也許她的工作沒有那麼重要。”“也許這只是巧合。”

這並非巧合。

拉迪亞·珀爾曼擁有麻省理工學院的博士學位。除了STP之外,她還發明了許多其他協定和技術。她曾在世界上一些最負盛名的科技公司工作。她發表了100多篇論文。她撰寫了網路設計領域的教科書——《互連:網橋、路由器、交換器和網路互聯協議》,該書被世界各地的電腦科學課程廣泛採用。

她甚至還寫了一首關於STP的詩,名為《算法韻律》:

“我想我永遠不會看到

比樹更美的圖。

一棵關鍵屬性

是無環連通性的樹…”

她才華洋溢、成就卓著,是現代網路的基礎。

然而,大多數人卻從未聽過她。

近年來,當記者開始稱她為「網路之母」時,珀爾曼本人卻提出了異議。她認為這個頭銜過於簡單化——彷彿她的貢獻可以用一個可愛的母性比喻來概括,彷彿她需要一個與「網路之父」相對應的性別角色。

她說得對。這個頭銜確實有其限制。但我們竟然需要討論如何稱呼她的貢獻,這本身就說明了問題所在:我們沒有一個統一的敘事框架來講述女性在科技領域的成就,因為幾十年來,我們一直刻意忽略了她們的故事。

珀爾曼從未公開抱怨自己缺乏認可。在訪談中,她總是實事求是:她解決問題是因為這些問題很有趣;她建構系統是因為這些系統需要建構。獲得認可並非她的目標。

但這種謙遜也帶來了代價:一代又一代學習電腦科學的學生,他們了解瑟夫和卡恩,卻從未聽過珀爾曼的名字。年輕女性進入科技領域時,因為前輩女性被歷史遺忘,而缺乏榜樣。一種「男性發明科技」的文化敘事,正是因為我們系統性地遺忘了那些真正做出貢獻的女性。

面對被忽視,珀爾曼的回應是什麼?她繼續努力。

她最終開發出了 TRILL(TR)。

沒有留言:

張貼留言