| Petrushka | |

|---|---|

Nijinsky as Petrushka | |

| Choreographer | Michel Fokine |

| Music | Igor Stravinsky |

| Libretto | Igor Stravinsky Alexandre Benois |

| Based on | Russian folk material |

| Premiere | 13 June 1911 Théâtre du Châtelet Paris |

| Original ballet company | Ballets Russes |

| Characters | Petrushka The Ballerina The Moor The Charlatan |

| Design | Alexandre Benois |

| Setting | Admiralty Square Saint Petersburg Shrovetide, 1830 |

| Created for | Vaslav Nijinsky |

| Genre | Ballet burlesque |

Petrushka (French: Pétrouchka; Russian: Петрушка) is a ballet by Russian composer Igor Stravinsky. It was written for the 1911 Paris season of Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes company; the original choreography was by Michel Fokine and stage designs and costumes by Alexandre Benois, who assisted Stravinsky with the libretto. The ballet premiered at the Théâtre du Châtelet on 13 June 1911 with Vaslav Nijinsky as Petrushka, Tamara Karsavina as the lead ballerina, Alexander Orlov as the Moor, and Enrico Cecchetti the charlatan.[1]

Petrushka tells the story of the loves and jealousies of three puppets. The three are brought to life by the Charlatan during the 1830 Shrovetide Fair (Maslenitsa) in Saint Petersburg. Petrushka is in love with the Ballerina, but she rejects him as she prefers the Moor. Petrushka is angry and hurt, and curses the Charlatan for bringing him into the world with only pain and suffering in his miserable life. Because of his anger, he challenges the Moor as a result. The Moor, who is both bigger and stronger than Petrushka, kills him with his sword (scimitar). The crowd watching is horrified, and the Charlatan is called to the scene as well as a police officer. The Charlatan reminds everyone that Petrushka is nothing but a puppet made of straw and cloth, and that he has no real emotion nor 'life'. As the crowd disperses, the Charlatan is left alone on the stage. At that moment, Petrushka's ghost rises above the puppet theatre as night falls. He shakes his fist and thumbs his nose at the Charlatan, making him flee, terrified. Petrushka then collapses in a second death.

Petrushka brings music, dance, and design together in a unified whole. It is one of the most popular of the Ballets Russes productions. It is usually performed today using the original designs and choreography. Grace Robert wrote in 1946, "Although more than thirty years have elapsed since Petrushka was first performed, its position as one of the greatest ballets remains unassailed. Its perfect fusion of music, choreography, and décor and its theme—the timeless tragedy of the human spirit—unite to make its appeal universal".[2]

Russian puppets[edit]

Petrushka performance in a Russian village, 1908瓦斯拉夫‧尼金斯基 (Vaslav Nijinsky) – 俄羅斯芭蕾舞史上的主要舞者和編舞家之一瓦斯拉夫·尼金斯基(Vaslav Nijinsky)是芭蕾舞界的里程碑式人物,他不僅因其非凡的舞蹈實力而受到尊敬,還因其重新定義了藝術形式的創新編舞而受到尊敬。他出生於 19 世紀末,成為一位充滿活力的文化偶像,以超越芭蕾舞傳統界限的表演吸引了觀眾。他充滿活力的詮釋和獨特的視野在舞蹈藝術上留下了不可磨滅的印記,永遠改變了舞蹈的感知和表演方式。本文深入探討尼金斯基的生活和遺產,探討他藝術的細微差別、他面臨的壓力以及他對芭蕾舞世界的深遠影響。來源:傳統文化。

Petrushka performance in a Russian village, 1908瓦斯拉夫‧尼金斯基 (Vaslav Nijinsky) – 俄羅斯芭蕾舞史上的主要舞者和編舞家之一瓦斯拉夫·尼金斯基(Vaslav Nijinsky)是芭蕾舞界的里程碑式人物,他不僅因其非凡的舞蹈實力而受到尊敬,還因其重新定義了藝術形式的創新編舞而受到尊敬。他出生於 19 世紀末,成為一位充滿活力的文化偶像,以超越芭蕾舞傳統界限的表演吸引了觀眾。他充滿活力的詮釋和獨特的視野在舞蹈藝術上留下了不可磨滅的印記,永遠改變了舞蹈的感知和表演方式。本文深入探討尼金斯基的生活和遺產,探討他藝術的細微差別、他面臨的壓力以及他對芭蕾舞世界的深遠影響。來源:傳統文化。

胡乃元、嚴長壽宣布「Taiwan Connection」無限期停演

‧2004年,在亞都麗緻總裁嚴長壽、雲門舞集創辦人林懷民以及新舞臺辜懷群老師的支持、鼓勵之下,久居紐約的知名小提琴家胡乃元,成立了Taiwan Connection,為旅居國外以及國內的年輕音樂家,搭建一個平台。

「Taiwan Connection」集聚臺灣海內外知名樂團音樂家,並號召眾多企業支持,把音樂帶向台灣各個角落,足跡遍及台東、花蓮、屏東、台南、彰化…,用音樂連結全台灣。在梅樹下、在操場上,為弱勢家庭的孩子、沒聽過古典樂的老人家演奏。他們用行動來回答,音樂家能對社會做什麼貢獻。

今年是「Taiwan Connection」音樂節舉辦的第11年。但經過一年長考,「Taiwan Connection」音樂節音樂總監胡乃元、發起人嚴長壽,決定「Taiwan Connection」將無限期停演。並將於11月14日出版《弓在弦上》一書,為這段精彩的音樂歷程做下紀錄,也讓更多人思索未來發展的方向,為台灣聽眾帶來新的想像。

胡乃元和嚴長壽坦言,「Taiwan Connection」成立初期十分艱難,只靠著參與者的熱情支撐,每年辦完他們甚至都不知道是否還會有下一年。幸好一路走來,接受各方支持,樂團規模逐漸擴大,去年表演「神之狂舞」曲目是TC演奏至今的高潮,不只票房亮麗,更受到業界盛譽。僅管如此,仍有許多問題等待解決。

「Taiwan Connection」成立之初,胡乃元希望拋磚引玉,邀請更多音樂家一起響應,把音樂帶到台灣各個角落。然而十一年之後,若只靠「Taiwan Connection」一年一次的巡演,推行音樂的成效難免有限。

胡乃元認為當音樂家不只是一份「工作」,而是需要付出「全部」的專注力。而對年輕的音樂學子來說,與其將夢想放在「做音樂家」,倒不如放在「做音樂」。他感謝過去參與TC的音樂家,每次上台,都想著如何為觀眾帶來感動。下台後,也能抬頭挺胸,問心無愧。他也感謝所有的聽眾及贊助者,多年來的熱情支持。嚴長壽認為政府需加強音樂推廣角色,音樂是需要廣泛推行和支持,而非只看重個別樂團成績。

「Taiwan Connection」今年將以演奏舒伯特的《偉大》,為十一年的音樂歷程暫時畫下句點。胡乃元表示《偉大》是舒伯特在知道自己得到絕症後寫下的,曲長約一小時,高低波折變化,象徵快樂傷心,寫盡人生百態。胡乃元從曲中聽見:「不管人生多辛苦,都應該抬頭挺胸面對問題」。他因此把此曲獻給「Taiwan Connection」後,那些一路相挺的無名英雄。(購票資訊:2014 Taiwan Connection 音樂節─《偉大》)

留下至少兩位故友的名字 Andrew Hu和林世煜大名...

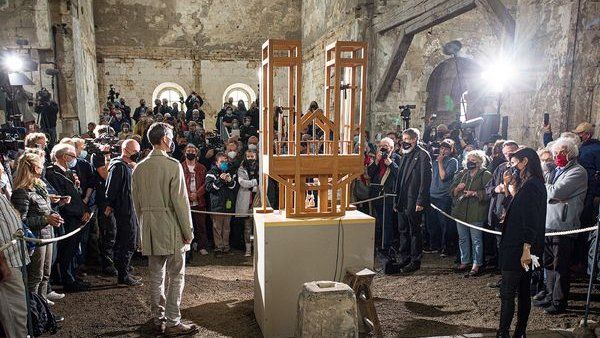

John Cage: Organ playing 639-year-long piece changes chord

The longest - and slowest - music composition in existence had a big day on Monday - it changed chord for the first time in two years.

Crowds gathered at a church in Germany to witness the rare moment, which is part of an artistic feat by avant-garde composer, John Cage.

The experimental piece, entitled As Slow as Possible, began in 2001.

Being played on a specially-built organ, it is not set to finish playing until the year 2640.

That's 616 years away. Looking at that period of time in the other direction - the Renaissance was starting to rumble into existence in Europe.

The composition, which in full is entitled Organ²/ASLSP (As Slow as Possible), has now had 16 chord changes.

Volunteers added another pipe into the mechanical organ to create the new sound, at the Burchardi Church in the German town of Halberstadt.

While the composition officially started in 2001 - it began with 18 months of silence, and the first notes only rang out in 2003.

Some people reportedly booked tickets years in advance to experience Monday's chord change.

The score is made up of eight pages of music, designed to be played on either the piano or organ. Though the instruction in its title - for the piece to be played as slowly as possible - was clear, no exact tempo was ever specified.

The last timethe chord was changed was exactly two years ago - on 5 February 2022. The next scheduled change will be on 5 August 2026, according to the project's website.

In contrast to this current performance of epic proportions, the piece's premiere in 1987 lasted just shy of 30 minutes. But subsequent performances, including a 2009 rendition by organist Diane Luchese, lasted 14 hours and 56 minutes.

This current, much longer rendition was born out of a meeting of musicians and philosophers following Cage's death.

For practical reasons, the mechanical organ was designed, using an electronic wind machine to push air into the pipes, while sand bags press down the keys to create the drone-like sound.

American composer John Cage, who died in 1992, was at the forefront of experimental and avant-garde music in the 20th Century.

His most famous piece, 4'33", is designed to be played by any combination of instruments - but musicians are instructed not to play them.

Instead, listeners hear the sound of their surrounding environment during the four minutes and 33 seconds the work lasts.

Born in Los Angeles in 1912, composer John Cage turned the world of music

on its head. He sought to free his work from the influence of his will,

opening it to randomness. And he proved that silence can also be music.

The www.dw.de Article

http://nl.dw.de/DTS?url=http%

A Musical (a) Anarchist or (b) Liberator Is Turning 80

By ALLAN KOZINN

Published: July 2, 1992

John Cage moments / 百歲

John Cage, 79, a Minimalist Enchanted With Sound, Dies

He died of a stroke, a hospital spokesman said.

The influence of Mr. Cage, who was also a writer and philosopher, spread far beyond the musical world.

He was a central influence on the work of the choreography of Merce Cunningham, whom he had known since they were students at the Cornish School of the Arts in Seattle more than 50 years ago. It was Mr. Cage who persuaded Mr. Cunningham to start his own dance company, with which Mr. Cage toured as composer, accompanist and music director. He was also an influence on the artists Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, who were his friends, and on several generations of performance artists.

With Three in One

In 1989, when the Anthony d'Offay Gallery in London brought together pages from Mr. Cage's 1958 "Concert for Piano and Orchestra," videotape of Mr. Cunningham's choreography and a collection of Mr. Johns's works in a show called "Dancers on a Plane: Cage, Cunningham, Johns," John Russell wrote in The New York Times about Mr. Cage's centrality in this constellation: "There was never a manifesto, a statement of position, a 'momentous' interview. He just does it, and the others do what they do, and in ways that everybody can sense and nobody can quite explain, the interaction of these three has consistently brought about astonishing results."

"Perhaps no one living artist has such a great influence over such a diverse lot of important people," Richard Kostelanetz, a writer who edited several books about Mr. Cage, wrote in a New York Times Magazine article in 1967. "Nowadays, even those critics who disagree with him respect his willingness to pursue his ideas to their 'mad' conclusions, and he was impoverished for too many years for anyone seriously to doubt his integrity."

In a career that began in the 1930's, Mr. Cage composed hundreds of works, ranging from early pieces that were organized according to the conventional rules of harmony and thematic development, to late pieces that defied those rules and were composed using what he called "chance" processes.

He composed for every imaginable kind of instrument, from standard orchestral strings to "prepared" pianos, altered by putting nails, paper, wood, rubber bands or other objects between their strings to make them sound percussive and otherworldly. He wrote electronic and tape works, and works that involved only spoken texts. His often impish scoring, in fact, might include radios, toys, the sounds of water being sipped or vegetables being chopped.

On the Nature Of Sound

His "Europera 5" -- sections of which are to be performed this weekend and next as part of a Museum of Modern Art Summergarden series in midtown Manhattan devoted to Mr. Cage's work -- juxtaposes 19th-century operatic arias, instrumental music by Mr. Cage, radio broadcasts and silent television pictures. And one of his most famous and provocative pieces, "4'33"," is 4 minutes and 33 seconds of silence, divided into three movements. Indeed, Mr. Cage considered virtually every kind of sound potentially musical.

"I think it is true that sounds are, of their nature, harmonious," he told an interviewer last month, "and I would extend that to noise. There is no noise, only sound. I haven't heard any sounds that I consider something I don't want to hear again, with the exception of sounds that frighten us or make us aware of pain. I don't like meaningful sound. If sound is meaningless, I'm all for it."

Not surprisingly, Mr. Cage, his music and his theories of composition have always inspired debate. Traditionalists have dismissed him as a prankster, a charlatan or an anarchist, and although performances of his music take place uneventfully today, there were times in the 1960's when his works evoked angry responses. At a New York Philharmonic performance of "Eclipticalis With Winter Music," in 1964, for example, a third of the audience walked out and members of the orchestra hissed the composer.

"I do what I feel it is necessary to do," he told an interviewer. "My necessity comes from my sense of invention, and I try not to repeat the things I already know about."

Mr. Cage was, in fact, the son of an inventor, and if there is a single thread running through his compositions and books, it is a sense of constant innovation, improvisation and exploration. Arnold Schoenberg, with whom he studied and whose rigorous 12-tone style inhabits an end of the contemporary music continuum opposite the place occupied by Mr. Cage, once described him as "not a composer but an inventor of genius," a quotation that Mr. Cage always said pleased him.

John Milton Cage Jr. was born on Sept. 5, 1912, in Los Angeles, and spent part of his childhood in Detroit and Ann Arbor, Mich., before moving back to California. An entrepreneur from the start, he had his own weekly radio show on KNX in Los Angeles when he was 12 years old. He had started to study the piano by then, and his programs featured his own performances and those by other musicians in his Boy Scout troop. He graduated from Los Angeles High School as class valedictorian.

He was ambivalent about his musical studies at first. He did not regard himself as a virtuoso pianist, and throughout his life he frankly spoke and wrote of his lack of traditional musical skills, going as far as proclaiming, in his book "A Year From Monday": "I can't keep a tune. In fact I have no talent for music."

In 1930, after two years at Pomona College, Mr. Cage went to Paris where he briefly worked for Erno Goldfinger, an architect with ties to Marcel Duschamp and other Dadaists whose work would later influence him. He also threw himself into the study of contemporary piano works he had heard at a performance by the American pianist John Kirkpatrick. He painted and wrote poetry, and it was during a visit to Majorca during this first European sojourn that he composed his first piano pieces.

Working as a Cook And Gardener

The European trip was followed in 1931 by a drive across the United States. When he returned to California, he took jobs as a cook and gardener. He also began giving lectures on modern art, keeping a step ahead of his subject by doing research at the Los Angeles Public Library.

At around this time, he also was becoming increasingly interested in the music of Schoenberg, who had jettisoned the hierarchical system of tonal harmony that had prevailed in Western music, and replaced it with a system in which the 12 tones of the scale were given equal weight. This notion appealed to Mr. Cage, and in 1933, after reading that the pianist Richard Buhlig performed some of Schoenberg's music, he sought Buhlig out and began to study with him. He also developed a harmonic system of his own, distinct from Schoenberg's, but similar in spirit, and used it to compose a Sonata for Two Voices and a Sonata for Clarinet.

Later in 1933, Mr. Cage traveled to New York City to study harmony and composition with Adolph Weiss. He also studied Oriental and folk music at the New School for Social Research with the iconoclastic composer Henry Cowell.

By the time Mr. Cage returned to California, late in 1934, Schoenberg had left Europe, where the Nazis had declared his music decadent, and had accepted a teaching post at the University of Southern California at Los Angeles. Schoenberg agreed to teach Mr. Cage counterpoint, harmony and analysis free of charge, as long as Mr. Cage promised to consecrate himself to music.

"Schoenberg was a marvelous person," Mr. Cage said last month. "He gave his students little comfort. When we followed the rules in writing counterpoint, he would say, 'Why don't you take a little liberty?' And when we took liberties, he would say, 'Don't you know the rules?' "

But Schoenberg showed little interest in Mr. Cage's own work. He declined to look at his pieces, even such formal exercises as fugues. And when Mr. Cage's early percussion works were performed, Schoenberg invariably said he was not able to attend.

Eventually, Mr. Cage drifted toward the world of dance. In 1937, he joined the modern dance ensemble at the University of California at Los Angeles as an accompanist and composer, and he formed his own ensemble to play his early percussion works. In 1937, he moved to Seattle, where he worked as composer and accompanist for Bonnie Baird's dance classes at the Cornish School. While in Seattle, he organized another percussion band, collected unusual instruments and toured the Northwest. It was also at this time that he met and began his lifelong collaboration with Merce Cunningham.

He returned to California in 1938 to join the faculty of Mills College. His works of this period were still fairly conventional, at least by his later standards. His "Music for Wind Instruments" and "Metamorphosis" (both 1938) showed a continuing allegiance to Schoenberg's 12-tone system, and his "First Construction" (1939), for a percussion ensemble that used sleigh bells, thunder sheets and brake drums, explored layers of interlocking rhythms.

But Mr. Cage was also beginning to explore new territory. His "Imaginary Landscape No. 1," composed in 1939, used variable-speed turntables, a muted piano and a cymbal. The next year he wrote his first piece for prepared piano, "Bacchanale."

In 1942, after brief stays in San Francisco and Chicago, Mr. Cage moved to New York City, which remained his home base thereafter. He again assembled a percussion group, which gave its first New York performance at the Museum of Modern Art in February 1943. The concert received a great deal of attention, not all of it favorable. Among the listeners who objected to Mr. Cage's eclectic instrumental arsenal, which included flower pots, cow bells and frequency oscillators, was Noel Straus, whose review in The New York Times said Mr. Cage's music "had an inescapable resemblance to the meaningless sounds made by children amusing themselves by banging on tin pans and other resonant kitchen utensils."

Soon after he arrived in New York, Mr. Cage undertook his first collaboration with Mr. Cunningham, "Credo in Us," and in the mid-1940's they toured extensively together. In 1947, Mr. Cage was commissioned to write "The Seasons" for the Ballet Society. A graceful, consonant work with a pronounced Indian influence that reflected Mr. Cage's growing interest in Eastern philosophy, "The Seasons" is one of his few scores for traditional symphony orchestra.

Mr. Cage's attraction to Eastern philosophy began around 1945, when he began an extensive study of Zen Buddhism at Columbia University. This interest had a profound and lasting effect on his work. "The Seasons" was an attempt to express the Indian view of the seasons as quiescence (winter), creation (spring), preservation (summer) and destruction (autumn). The Sonatas and Interludes for Prepared Piano, an exhaustive, hourlong study of the instrument's capabilities, is the Indian concept of "permanent emotions," including the heroic, erotic, wondrous, mirthful and sorrowful.

A Discovery Of 'I Ching'

In 1950, after returning to the United States from a tour of Europe with Mr. Cunningham, Mr. Cage discovered the "I Ching," the Chinese "book of changes" that one consults after tossing a set of coins. This method gave Mr. Cage the idea that lies at the heart of his "chance" compositions. If readings in the "I Ching" could be governed by the chance toss of a coin, why couldn't musical composition? Indeed, why couldn't musical works be created using chance processes with the audience looking on, so that the composition and the performance were one and the same?

Among Mr. Cage's earliest works using this principle was "Music of Changes" (1951). The musical elements of the piece -- pitch, duration, timbre, dynamics -- were determined by the performers using charts based on the "I Ching" and by tossing coins. "Imaginary Landscape 4" (1951) explored chance procedures in a different way: The work is scored for 12 radios, operated by two performers. One performer changed stations, the other worked the volume control. The dial turning was precisely notated, but what was heard depended on what was being broadcast during the performance. "Europera 5" (1991) works similarly.

As he continued writing chance works, Mr. Cage developed a novel view of composition, in which he came to regard composing not as a way of imposing order on nature, but as a way of creating the circumstances in which art could adapt itself to its surroundings. Probably the purest example of this philosophy is Mr. Cage's "4'33"" (1952), in which a performer stands silently on stage. Inevitably, listeners were forced to focus on nonmusical sounds, or in the case of an unusually quite audience, on the quality of silence itself.

Mr. Cage's explorations repelled listeners and composers committed to music's traditional qualities, but attracted experimenters like Earle Brown, Christian Wolff, Morton Feldman and David Tudor, with whom he collaborated on the Project of Music for Magnetic Tape. Mr. Cage's first tape work was "Imaginary Landscape No. 5" (1952), composed for a dance piece by Jean Erdman. Mr. Cage's method here was to tape 42 phonograph records, chop the tapes into short pieces, and to use chance operations to determine how the pieces of tape should be reassembled. Pieces like "Williams Mix" (1952) and "Fontana Mix" (1958) used tape in even more complex and convoluted ways.

But Mr. Cage did not abandon acoustical music, nor did he run out of unusual ways to write pieces. In "Water Music" (1952), almost as much a Cageian classic as "4'33"," he had a pianist pour water from one pot into another, and perform various other actions using a radio, a whistle and a deck of cards.

As his works, and the varied reactions to it, brought him increasing notoreity, Mr. Cage came to be increasingly in demand as a lecturer, teacher and performer. He undertook tours of Europe and Japan with Mr. Tudor, one of his electronic music collaborators, and he continued to tour with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. He taught classes in experimental music in Darmstadt, Germany, and lectured on his theories of indeterminate composition at the Brussels Worlds Fair in 1958. And at the New School, in New York, he taught classes on mushroom identification, another of his lifelong interests. Of Experiments In Later Works

Mr. Cage's major works since the late 1960's include "Hpschd" (1969), a collaboration with Lejaren Hiller for 7 harpsichords, 51 tapes, films, slides and colored lights; "Cheap Imitation" (1969, orchestrated 1972), based on a piece by Satie, which keeps the original rhythmic patterns but replaces this French composer's pitches with notes selected through chance procedures; "Etudes Australes" (1974-5), a virtuoso piano work with a score based on astronomical charts; "Roaratorio" (1979), an electronic piece containing thousands of sounds mentioned in James Joyce's novel "Finnegans Wake," and the five "Europera" works, composed from 1987 to 1991.

Mr. Cage's books include "Virgil Thomson: His Life and Music" (1959), written in collaboration with Kathleen O'Donnell Hoover; "Silence" (1961); "A Year From Monday" (1967); "M" (1973); "Empty Words" (1979), which he also regarded as a performance piece, and read from at this year's Summergarden concerts; "Theme and Variations" (1982); "X" (1983), and "I-IV," a collection of the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures he delivered at Harvard in 1988-89.

He also amassed a sizable catalogue of visual works -- photography, monotypes, prints, etchings, paintings and some of his more graphic scores -- from 1969 to this year.

In his later years, Mr. Cage was the recipient of many honors. His 60th, 70th and 75th birthdays were celebrated with extensive concert series and tributes around the world, and this year's celebrations anticipating his 80th birthday are well under way. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1978. He received the New York Mayor's Award of Honor for Arts and Culture in 1981 and, in 1982, the French Government awarded Mr. Cage its highest honor for distinguished contribution to cultural life, Commandeur de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres.

Mr. Cage was a soft-spoken, mercurial man who remained keenly interested in new music. He made himself easily accessible to young composers and critics, and was often seen at concerts in downtown Manhattan.

Mr. Cage's marriage to Xenia Andreyevna Kashevaroff ended in divorce in 1945. From 1970 until his death, he lived with Mr. Cunningham.

There are no immediate survivors.

The obituary also rendered the titles of two of Mr. Cage's works incorrectly. The book in which his Norton Lectures were collected was "I-VI"; the work performed by the New York Philharmonic in 1964 was "Atlas Eclipticalis With Winter Music."

沒有留言:

張貼留言