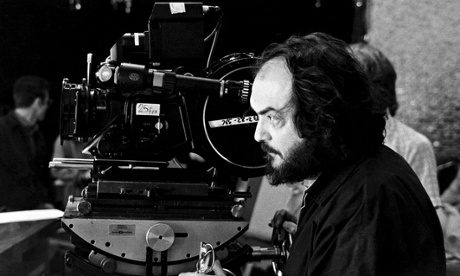

Director Stanley Kubrick—who died on this day in 1999—had a costly obsession with perfection. He once shot the closing of a car door more than 70 times before he was satisfied it looked right

Each image has its own narrative, laying down the blueprint for a technique that Kubrick described with the words: “Well, I never shoot anything I don’t want.”

Stanley Kubrick: Photos taken as a teenager

This is how the Space Odyssey director first developed the vision that set him apart.

WWW.BBC.COM

6 June 2014

Stanley Kubrick: Photos taken as a teenager

By Fiona Macdonald

In April 1945, at the age of 16, Stanley Kubrick snapped a newspaper vendor looking at headlines that shouted ‘Roosevelt Dead!’. This was no shoot-from-the-hip picture, however: the future director of 2001: A Space Odyssey and A Clockwork Orange gave the vendor careful instructions on how to pose, offering an early sign of the vision that would have him lauded as one of the most important directors of the 20th Century.

Kubrick sold that photo to New York’s Look magazine, initiating a relationship that lasted until 1950. A new show at the Kunstforum Viennareveals a selection of the 27,000 photographs he took while on assignment for the magazine, a five-year stint that served as an apprenticeship in crafting visual stories.

A shoeshine boy gazes up at a flock of birds; a besuited man stands in front of a circus balancing act; a showgirl applies lipstick in the mirror. Each image has its own narrative, laying down the blueprint for a technique that Kubrick described with the words: “Well, I never shoot anything I don’t want.”

The magazine photographs allowed Kubrick to experiment in composition, atmosphere and timing to develop his narrative style. Offering a glimpse of a lesser-known chapter of his career, they also signal his move into directing: Kubrick’s first film, a documentary made in 1951, focused on the boxer Walter Cartier – a subject he had photographed for Look.

Dangerous Minds

Stanley Kubrick shoots the N.Y.C. subway, 1946

Stanley Kubrick shoots the N.Y.C. subway, 1946

In the summer of 1945, Stanley Kubrick, many years before he was the acclaimed director of Dr. Strangelove, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and A Clockwork Orange, had a series of photographs published in LOOK...

DANGEROUSMINDS.NET

(2013 補:當時南方朔先生談到某山內部都是雷達顯示......可能是60年代著名的Dr. Stranglove電影中的War Room嗎----這電影史上最壯觀之一景. 連雷根入主白宮時都要先問:它在那? "報告總統:白宮沒這戰情室!" 據說雷根回答:"電影中不是有這嗎?")

Kubrick recalled by influential set designer Sir Ken Adam

Peter Sellers, pictured with Sterling Hayden, played three roles in Dr Strangelove

Peter Sellers, pictured with Sterling Hayden, played three roles in Dr Strangelove

Steven Spielberg told production designer Sir Ken Adam his work for Stanley Kubrick's Dr Strangelove included the best movie-set ever built. Kubrick's dark comedy is now regarded as a Cold War classic. Fifty years on, Sir Ken remembers his time working for Kubrick as a magnificent adventure - if you could take the stress.

Sir Ken Adam sits in his house in central London and summons up memories of Stanley Kubrick. His affection for the director is obvious and at times there's real emotion in his voice.

"I was incredibly close with him. It was almost like an unhealthy love affair between us. And I had a breakdown eventually."

Sir Ken was born Klaus Adam in 1921. The prosperous Jewish family fled Germany as he entered his teens but his Berlin accent remains. Even in retirement he is British cinema's doyen of production design, whose credits include most of the Bond films up to Moonraker (1979).

When summoned in 1963 to a London hotel to meet Kubrick he was aware the American director could be a demanding taskmaster. But the encounter proved unexpectedly easy.

"We were sitting across a table in the living room and all the time we were discussing Strangelove I was doodling. Immediately Stanley was fascinated by my doodles so we got on like a house on fire. Most days during production I drove him to the studio in my E-type Jaguar.

"I recommend this as a way to get to know your director.

"You know, in some ways Stanley was naive and we were both young and full of enthusiasm. At first I thought well this is amazing: here is a man who is supposed to be one of the most difficult directors ever and he accepts everything I've designed. All I have to do is hand it to the art department and they will get cracking. Well, little did I know."

The set everyone remembers from Dr Strangelove is the enormous war room. It is like something out of a dream - or perhaps a nightmare.

"It came as a big shock when two or three weeks into filming I realised Stanley wasn't so easy-going after all. I'd designed the war room as a split-level set with actors on each level but he came to me and said Ken what the hell am I supposed to do with 60 people on the upper level?

"They're standing around with egg on their faces doing nothing - get rid of the upper level. I said: 'Stanley, now you tell me. But of course he was right'.

"We had big rows because on other films I'd been used to telling the director where to do his establishing shot from. But Stanley said the hell with you I'm not putting my camera there - and you'll thank me in the end."

The war room is an acknowledged classic of movie design and Sir Ken can't resist quoting the biggest compliment he ever received.

"I was in the States giving a lecture to the Directors Guild when Steven Spielberg came up to me. He said 'Ken, that War Room set for Strangelove is the best set you ever designed'. Five minutes later he came back and said 'no it's the best set that's ever been designed'."

Sir Ken Adam designed the sets for seven James Bond films

Sir Ken Adam designed the sets for seven James Bond films

But by the end of the Strangelove shoot Sir Ken had resolved never to do another Kubrick film: the process had been too exhausting. "We agreed to part as friends and I was so relieved."

But there was to be a second and more difficult chapter in the men's relationship.

"In 1972 he approached me about designing Barry Lyndon but I think he decided I was too expensive and he employed someone else. Three weeks later I was in the south of France doing a film and the phone went.

"It was Stanley sounding like a little New York boy: he said the designer hadn't worked out and he needed me. He schmoozed me into doing the film and I was never happy about it."

Barry Lyndon was an ambitious historical epic to be shot on location. But there was a problem: Kubrick wanted to find locations while barely leaving his family home in Elstree, north of London.

"So we set up in his garage a little war room, with Ordnance Survey maps on the walls and pins everywhere. We had an army of young photographers to go looking at buildings and possible locations and every evening we looked at what they'd done.

"He would be enthusiastic about a particular bed or whatever in a slightly voyeuristic way.

"But we'd have big arguments because I would say: 'No that's Victorian but the film is set in Georgian times'. Well Stanley was so competitive that he bought almost every book available on Georgian architecture so he could argue with me. But none of this was getting the movie made because the buildings and peaceful locations he wanted just don't exist anymore near London.

"It was nerve-destroying. But after five months I got Stanley to switch production to the Republic of Ireland - which I thought was my masterstroke."

Stanley Kubrick had a reputation as a demanding director

Stanley Kubrick had a reputation as a demanding director

As Sir Ken recalls it, once in Ireland Kubrick changed totally. "He saw himself as General Rommel, who he admired greatly. He equipped all of us with Volkswagens so we became a complete mobile unit driving around Ireland finding locations.

"I spent weeks being chased through fields by bloody bulls. I was going crazy but this was Stanley's character - with all his fears and anxieties he was relentless. "

When Letizia, Sir Ken's Italian-born wife, came out to Ireland she was shocked at his state of mind. She persuaded him to return to England and see a doctor for the sake of his health.

"So now I was in hospital in England with a breakdown. Stanley rang the hospital every day to see how I was doing and if I was still alive. The day I left he phoned me at home.

"He said: 'Ken you were right: we're going to change the way we're making the film and you'll love it. I'm sending a second unit to Potsdam in Germany to pick up extra material and I want you to direct it."

Sir Ken laughs. "Well I found that idea such a huge shock I had to go straight back to the clinic and check in again."

After Barry Lyndon, Sir Ken decided this time, whatever his admiration for Kubrick, the two would never work together again. It was a vow he adhered to with one brief and slightly bizarre exception.

In 1977, designing the Bond film The Spy Who Loved Me, Sir Ken had built a vast set at Pinewood studios. It included a supertanker which was proving hard to light.

"So I called Stanley up and asked him down to Pinewood to give me ideas. At first he said I was out of my mind but eventually he agreed to come on a Sunday when only security were around.

"He spent three or four hours with me telling me how he would light the stage. And of course the whole thing being in secret appealed to Stanley's sense of drama. But I knew we would never work together again. And Stanley didn't ask - he'd been so scared when he saw what happened to me half way through Barry Lyndon."

In 2003, Ken Adam received a knighthood - the first for a film production designer. Kubrick died in 1999 at the age of 70, one of the world's most admired and most demanding directors.

Scenic design (also known as scenography, stage design, set design or production design) is the creation of theatrical, as well as film or televisionscenery. Scenic designers have traditionally come from a variety of artistic backgrounds, but nowadays, generally speaking, they are trained professionals, often self taught with a M.F.A. degrees in theatre arts. The beauty of a scenic design can produce the most unforgettable memories of life. Scenic art should provide an experience that engages your heart and mind. It takes you to a person, place or thing that can cause us to value it.廖祥雄

2006出版個人自傳『電影導演‧電影官』,篇幅長達五十數萬字,詳述個人生平、工作經歷。

廖祥雄 - 財團法人國家電影資料館/ 台灣電影數位典藏中心Chinese ...

www.ctfa.org.tw › 影人目錄 › 導演 - Cached - Translate this page1933年出生於台中,因父親是公務人員,所以自小接受的是日式教育,直至抗戰勝利後,才開始接觸中文。大學時期曾修讀「視聽教育」課程,又於畢業後任職於師大視聽 ...

------

Diane Arbus

Diane Arbus

Born: March 14, 1923, New York City, New York, United States

Died: July 26, 1971, Greenwich Village, New York City, New York, United States

Spouse: Allan Arbus (m. 1941–1969)

Happy birthday to Diane Arbus, one of the most influential and provocative artists of the 20th century. An iconic image that embodies the awkward tension between childhood tomfoolery and primal violence, this has become one of the most celebrated photographs in the history of the medium.

This photograph will be on view in “diane arbus: in the beginning” opening at The #MetBreuer on July 12.

Museum Associates/LACMAA “Shining” moment from “Stanley Kubrick,” on view at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

“Stanley Kubrick,” a sprawling exhibition devoted to the director’s oeuvre, opens at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art on Nov. 1. The museum’s director, Michael Govan, explained that “While it’s impossible to screen a filmmaker’s career all at once in an exhibition, the nature of a museum’s gallery spaces gives the viewer the unique opportunity to wander through the filmmaker’s mind, his creative process and the meaning of his work, and to make comparisons and contrasts between the works.”

“Kubrick” was originally organized (in collaboration with the director’s estate) by the Deutsches Filmmuseum in Frankfurt, Germany, but when Govan decided to bring it to L.A., he asked the production designer Patti Podesta to reframe the show for LACMA. Podesta (a trained artist who has worked in the film industry for many years, on films including “Memento,” “Recount,” “Bobby” and “Love and Other Drugs”) has designed a stunning installation for the more than 600 objects (scripts, sketches, costumes, cameras, props, still photos, posters and film clips) that make up the exhibition. Podesta created a series of striking visual tableaus, pulling together the various physical artifacts surrounding each film and putting them together in a new and meaningful way. “I wanted to represent all parts of filmmaking in the exhibition,” she says. “Kubrick controlled everything. He thought everything through. With each of his films, he reworked the material so that each one is a whole, a complete environment. For the exhibition, it was important to create an atmosphere for his work, something that people would feel like a sensation.”

Massive backlit transparencies are like signposts in the exhibition, leading viewers through the director’s films. Kubrick’s many camera lenses — he was obsessed with technology — are displayed like jewels in cases near the beginning of the exhibition. To tell the story of the range and depth of his vision, each of the films is connected to a theme. In the “Noir” section, Podesta commissioned the scenic painter Gary Lloyd to paint gradated gray-to-black walls, and in the gallery devoted to “Barry Lyndon,” Lloyd painted a bucolic background of blue sky and clouds. Podesta also included works by a number of artists to reinforce the connection between art and film. Kubrick was a voracious consumer of all things visual and constantly looked at art and art books. A black plank sculpture by the artist John McCracken alludes to the omnipresent monolith in “2001,” while the wall-size blow up of the twins from “The Shining” twins conjures Diane Arbus’s famous photograph, and a prop table holds art books opened to the pages from which Kubrick quoted, literally, in “Barry Lyndon.”

Govan says that “Stanley Kubrick,” which is presented in L.A. with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences, is a taste of things to come for a city where art and film are powerful forces, but which have long occupied separate arenas. In 2016, the Academy will open its own museum in the historic May Company building next door to LACMA. A series of screenings offered by both LACMA (this fall) and the Academy (next spring) will give viewers another opportunity to immerse themselves in the haunting, compelling worlds of Stanley Kubrick.

“Stanley Kubrick” is on view at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art through June 30, 2013.

The Shining: the film that frightened me most

It wasn’t so much the axe-wielding maniac, the twins or the corridor of blood that left Peter Kimpton sleepless, but that he began to doubt his own eyes on first view of Kubrick’s classic

• More from The film that frightened me most

Share 1146

inShare

2

Axe scene from The Shining with Shelley Duvall.

A rather anxious moment during the door scene from The Shining with Shelley Duvall. Photograph: Ronald Grant Archive

No matter how hard things might become, you can always trust your own perceptions. It’s the bottom line, the safety net, the final refuge. It’s sanity. Well, that’s what I’d always told myself. But when I first saw The Shining on TV as a teenager, I felt like I’d been hit by a bus. Or possibly a snow cat. And Jack Nicholson was probably waiting for me behind a door - with an axe.

Admittedly I was going through a bad patch. I’d just had an angry falling out with my best friend. And a girl I really liked was blowing hot and cold. It was really upsetting me. I was having rows with my family, and there were always fights, not only at home, but at school, and the night before I’d seen someone getting knifed outside a club in central Manchester. I can still picture the blood on the pavement. The whole world is going mad, I said to myself. But it’s still OK, I know what I see, and I know who I am. But then, in this very challenged state of teenage alienation, I was suddenly at home, alone, on Saturday night, and with the perfect storm in film experience, about to break.

2330 0829 2014 五

.庫伯力克的"鬼店(SHINING)"

公視 復刻經典影展 鬼店電影完整劇情介紹及精彩對白

電影完整劇情介紹及精彩對白

The Shining: the film that frightened me most

It wasn’t so much the axe-wielding maniac, the twins or the corridor of blood that left Peter Kimpton sleepless, but that he began to doubt his own eyes on first view of Kubrick’s classic

All at once I am flying across a Colorado lake and mountains, with a yellow VW Beetle down below, heading towards the vast, bleak, Overlook hotel. Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) is calmly agreeing to be caretaker with wife Wendy and son Danny over the winter period, but everybody else is heading in the other direction. He’s grinning, and says he hopes to get some writing done. In my experience that’s already a bad sign. And alongside the splendour of the setting, there’s a blandness about the packing away, the end-of-season closing down. It’s a normality, with aura of something not right. This, and the early part of the score, really gets under your skin. There’s a powerful sense of foreboding. The combination is dream-like, inexorable, and as Stanley Kubrick undoubtedly planned, makes you feel vulnerable.

There are many terrifying things in Kubrick’s horror masterpiece. There’s the rattling, stabbing, jagged violins at key moments using music from Krzysztof Penderecki’s Polymorphia. Then there’s little Danny’s imaginary friend, Tony, who lives in his finger, or mouth or wherever, and speaks in Exorcist-type robotic tones, climaxing in the REDRUM /MURDER mantra written on the bedroom door. There’s the horrible death of amiable head chef Mr Halloran, Danny’s psychic shine friend, chopped down when all he does is to drive through the snow to see if they’re alright. No! He killed Scatman Crothers, the voice of Hong Kong Fooey and occasionally on Scooby Doo. Then there’s the woman in room 237, who commits the mortal sin of turning old and rotting very quickly in the middle of a naked snog. Urrgh. Shiver! And then, after the brilliantly innovative floor-level Steadicam footage of Danny tricycling through the corridors, there’s the terrible twins. OK, Let’s play it.

Yet the scariest thing about The Shining is how it always plays with your perceptions. The most shocking revelation comes in the typewriter scene, where Wendy, played by Shelley Duvall, who does frightened like nobody else and is film’s answer to Edvard Munch’s The Scream, discovers that her husband has typed, over and over, nothing but reams of the same phrase: “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.” As she glances through, the typing also contains fleeting glimpses of the phrase mutate into “dolt boy” to “adult boy”.

But even before this catastrophic moment, Kubrick seems to have been playing subliminal games. I did not notice this until years later, but in a precursor scene in the same Colorado lounge, when Jack tells Wendy not to disturb him when he is writing, the typewriter changes from a small white model to a large grey one, and a chair in in the background disappears, reappears and disappears. The film is full of other object and hotel layout anomalies which subconsciously cause us disquiet. They simply cannot be continuity errors from a director so well known to be painstakingly meticulous. So, after Wendy’s discovery, a central scene unfurls in which Jack explains his “obligations”.

Although there’s nothing friendly about a river of blood in a corridor, mental breakdown can be just as frightening as physical horror. Much has been said about the hidden messages in the film, that it plausibly refers to the killing of native Americans, or more obscurely the Holocaust, or perhaps even less likely, clues that Kubrick helped create false footage of the Apollo 11 moon landing. Much of this is discussed in the Rodney Ascher’s interesting 2012 documentary, Room 237.

But the dialogue in the bat-swinging scene for me hits the heart of the horror, the centre of this maze of corridors, hedges and carpet patterns, and Jack’s so-called minotaur within it. Jack seems to turn on his family not because of visions or demons, but because he cannot find a proper job, a role, an identity, and balance this with ordinary family life, and adulthood. He has driven himself mad from an obsession with his contractual obligation at the Overlook hotel. The feeling is shaped by his offbeat, surreal encounters in the dining room with the ghosts of barman Lloyd and caretaker Grady. He tells his wife “I gave my word’ - and that she doesn’t understand his “responsibilities”. Here is the banality of evil from everyday life, out of drudgery, and that is key to why it’s all so frightening.

But that doesn’t deny me being absolutely terrified by such scenes as when Wendy glimpses a man dressed as a rabbit appearing to give another man a blowjob in the 1920s. The scariness, the first time, came because it happens quickly, the camera zooms as they look back at you, and because you’re not really sure what you’re seeing. I found myself doubting my own perceptions.

While it isn’t the actual plot climax to the film, the absolutely most chilling moment is also the funniest. I’m referring, of course, to the door-chopping scene, with Nicholson’s twisting nursery rhymes and where he improvised a phrase from the Johnny Carson show. Kubrick, living in the UK at the time, didn’t get the reference at first, and nearly cut it. It still makes me jump, even though I know what’s coming up.

The film ended. And as Jack sat frozen in the maze, I sat frozen in a cold sweat to the sofa. I didn’t sleep at all that night. My parents came home and I locked my bedroom door, but that wouldn’t have stopped Jack. And when I eventually did sleep the next night, it was far from restful then, or for several weeks. Why? Not so much due to scenes of bloody horror, but more because I wasn’t really sure what I was seeing, and it several years for me to understand why. Is this a shared experience, or was I going slightly mad?

沒有留言:

張貼留言