+2The 2009 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to Herta Müller, a Romanian-born German novelist and poet, for her work depicting "the landscape of the dispossessed" with "the concentration of poetry and the frankness of prose". Müller's writing, including works like The Land of Green Plums and The Appointment, explored life under the repressive Ceaușescu regime in Romania, using fragmented language and powerful imagery to convey themes of oppression, silence, and survival. 柏林訪2009諾貝爾文學獎得主荷塔.慕勒文◎蔡素芬

閱 讀荷塔.慕勒(Herta Muller)的小說,不得不被她流盪於故事間的冷靜與蒼涼的敘述姿態吸引,她在文句間營造的比擬與對比式語言,常折射出生存哲學,在冷靜中帶著痛苦。我 試著從她的語言去了解極權社會下,生命面臨威脅與無望的心理狀況,也試著感受她以詩的語言營造出來的敘述能量。

她在台灣出版的第一本小說中文譯本《風中綠李》,敘述羅馬尼亞的獨裁者社會,幾個青年如何受到監視,在失去個人自由與對未來沒有展望的情況下,一一自殺或被謀殺。

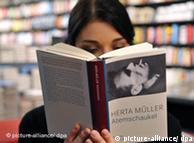

即將出版的第二本中譯本《呼吸鞦韆》即是她進入諾貝爾文學獎史冊的臨門一腳,書成於2009年,她亦於當年獲諾獎。

《呼 吸鞦韆》以1945年間俄國要求羅馬尼亞以境內17至45歲的男女德國人為勞役,遣送到俄國勞役營做為重建俄國的苦力為背景,敘述一名18歲的青年被送到 勞役營,臨去的心情是寧願被送到勞役營也不願待在每塊石頭都長著監視之眼的羅馬尼亞,但在勞役營的五年經驗,卻是人生中最悲痛、最難以忘懷的經驗,尤其他 的同志身分,在勞役營必須遮遮掩掩,一旦被識破,必定沒命。小說由此,講述了勞役營沒有人性尊嚴的勞動生活,和一名同志在感情生活上如何寂寞地活著、寂寞 地與勞役營的記憶糾纏。

小說中的主人翁取材於和她一樣從羅馬尼亞回到德國,曾獲德國最負盛名的布希納文學獎(Georg-Buchner- Preis)的詩人兼翻譯家奧斯卡.帕斯提歐爾(Oskcar Pastior),及她母親與村人等有勞役營經驗者的口述。當然,現實的故事,以文學的手法經營,就會有作者眼光的詮釋,慕勒以她反極權的正義之眼看待營 中所發生的事,反映於作品,是充滿感情與悲傷的記憶傷痕。而我在閱讀間仍不得不受她詩意的語言吸引,是詩的意境,讓所有發生的,都產生了滲入人心的力量。

6 月,在台北歌德學院的引線下,我和詩人鴻鴻有幸能於「台德文學交流計畫」執行期間,與慕勒在柏林會面,行前中譯本出版公司提供我們即將付梓的《呼吸鞦 韆》,讓我們有機會更了解慕勒的作品,我致意慕勒的德文出版連繫人,希望這場會晤可以對慕勒做些訪談,得到慕勒的同意。慕勒約我們在柏林文學館見面,17 日下午,我們在文學館花園等待她,文學館的入門處不大,一入門是庭前花園,左邊是咖啡座,已經坐了不少人,陽光閃爍的午後,離約定時間不到,慕勒邊走邊抽 菸,瀟灑地從門口走進來,嬌小的身影,造形俐落的短髮,黑洋裝加灰綠薄外套,整個人透顯出來的氣質相當獨特。

她一看到我們就露出笑容,我們 一行包括我、鴻鴻、為我們翻譯的胡昌智先生及台德文學交流的推動人之一唐薇小姐。笑容使氣氛親切,坐定後,慕勒主動問我們在柏林好不好,她提起中國買下她 所有作品的版權,但擔心《呼吸鞦韆》裡的同志身分在中國有禁忌,若作品因此被改,將失去作品的意義。我們的話題由此開始,我問她在《風中綠李》中,女主角 與女性好友的友誼似乎也介於精神上的同志傾向,她回說,不是同志,是姊妹情誼,在極權國家,人們的相處很容易和同性走得很近,甚至可以手牽手,那是一種淳 樸的、互相取暖的友誼。

寫作是重建生活經驗的途徑

我接著 問,她的文字充滿詩的意象,常有跳接的距離美,這種文字語言風格的運用,主張的是什麼?她說,自己既非心理學家、社會學家,也非歷史學家,自然不採用紀實 的語言,她所選擇的語言,只不過是文學的語言罷了。語言對她而言,是一種途徑。而字裡行間流露的詩意,不僅是為了成就美學表現和寫作宗旨,更是文學中「事 實真相」的肌理;這所謂的「事實真相」是被創造出來的,「語言」是會創造事實真相的,它會帶領作家,前往一個前所未知的境地,創作超越其自身經驗的作品。 其實,人生並不存在於語言當中,因為生活不會撥給語言時間,像是在攸關生死時,誰也顧不了語言,能夠顧及的也只有一樣,那就是保命。由此可知,寫作是重建 生活經驗的途徑,而這個途徑則是由語言和文字精砌而成的,它是百分之百的人為創造,畢竟,人生只會義無反顧地往前走,並不會停下腳步,等待你來撰寫它。

慕 勒除了小說外,也寫詩、散文、評論,就小說中的詩語言部分,我想了解更多關於她對詩和小說的看法,因而問她,她同時寫詩和小說,這兩者有寫作目的性的區別 嗎?我指的是就表現手法和意義上,她是就功能性回答。她說,沒有真正的目的,書本都是對個別的人有影響力,讀了一本書後,我們常期待這本書能產生什麼效 果,但通常是個人讀書後都有個人的吸收。她受不了作品被做為商業產品對待,在極權政治下,文學被工具化了,他們知道文學的任務為何,在羅馬尼亞極權政府統 治時代,他們會說「我們所需要的文學」,意味禁止某些作品出版。

我順勢說在中國,作品仍需受審查,有必要還得刪改。鴻鴻也說,她的作品在台灣出版不可能被改任何一個字。

她 延伸出更多關於刪改作品的談論,她最初在羅馬尼亞出版小說,曾被刪改,現在作品集在中國出版,也擔心作品被改。她表示,中國的軍備擴張令人感到恐懼,他們 如果想控制什麼的話,完全可以全力來做,中國目前在全世界的購買力強,影響力很大,但專制體系令人覺得恐怖,中國彷彿在向世界證明,無需透過民主,便能推 行各項目標,這種思維實在很令人懼怕。而且他們漠視個人尊嚴,不尊重個人,從不以「個人」做為考量事物的準則,因此中國對待世人的態度,才會如此狂傲自 大。我因此說,中國的出版社能夠出版她的作品,也算相當有勇氣。但她不知道可能翻譯成什麼情況,擔心自己的翻譯作品失真。我強調台灣的出版社要求翻譯要忠 於原著。

故鄉是講出來的內容 不是語言本身

我說她的作品對 人際關係有很特殊的形容,帶有哲學性語言。她說,當她在思考「專政」為何能夠有效運作時,不得不關注人性百態。有人扮演見證者,大多數的人則選擇扮演制度 的追隨者。他們之所以會這麼選擇,其實也不盡然是為了謀得好處,反倒是想要避免惹禍上身。有一些人選擇沉默設法置身事外,而有些人則是堅持反抗到底,然而 角色形形色色,其中並無明確的界線和分類。每個人天生為人皆有相同的本質,生長在相同的環境下,為何有人會成為沉默者,有人會成為壓迫人的罪犯?是什麼樣 的事件,能夠造就如此懸殊的發展?她不斷地思索。她明白這一切並非源自家庭的影響,否則,出身於官宦之家的孩子,長大後不會成為異議分子;窮苦家庭的小 孩,更不會成為黨內高層,但究竟是什麼決定了這一切?她百思不得其解。而人性萬般複雜,人最看不清的就是自己,這一切是她開始觀察人性的原因,她認為最值 得討論的是人們評斷一切的「標準」:例如,你能與某人成為好友,關懷他且保護他,可是你卻偏偏受不了某人,至於原因為何,自然是無從解釋,正如極權專政為 何至今仍能存在,同樣也是無從解釋。

她一直在思考怎麼對抗極權,而藝術讓人有置身點,藝術也會造就態度。閱讀不一樣的書籍,便會造就不一樣 的觀點。對她而言,書籍的時代性最為重要。她讀遍所有討論國家社會主義(納粹)的著作,當中談到語言濫用的現象。然而從閱讀中,她清楚地觀察到國家社會主 義如何濫用語言,將語言變成手段,樹立了語言樣板,從中自然也形成了特定的態度。她說,語言只能尋找,運用語言便能創造一切,好壞皆然。

對 於語言的使用,她更激昂地說明自己的看法,認為語言本身不是故鄉,故鄉是你講出來的內容,語言只是工具而已。今年2月德國基民黨(CDU)和基社盟 (CSU)為響應聯合國教科文組織推廣的國際母語日,舉行了「語言(母語)即故鄉」討論會,荷塔.慕勒也受邀出席。席間她提出自己的看法,認為語言並非故 鄉,故鄉乃人們所談所指,在於談論的內容。她說,政客最擅長操作語言,一旦政治把持了語言,後果將不堪設想。她忠於自己看法和立場,講出與其他人不同的看 法,主辦單位一再說她是諾獎得主,而不談她的看法,讓她覺得很不自在;她強調德國的諾貝爾文學獎得主湯瑪斯和赫塞都是從這個國家流亡出去的,她也是從極權 國家不得已回到德國的,主辦單位應該知道語言和故鄉之間的關係。

拼貼詩是嗜好 也是創作

鴻 鴻對她的拼貼詩相當好奇,問她是否只是一種遊戲或是有意地把社會性語言拆解為個人的語言?她說拼貼詩是一個創作形式,與自己的背景有關。住在羅馬尼亞時, 只有政黨報紙,油墨都留在紙上,到了德國,發現報紙雜誌都印得很漂亮,丟掉太可惜,尤其廣告上的文詞都很有意思,她就把那些剪下來,剛開始是貼在明信片 上,再寫自己的一句話,寄給朋友。剪貼變成一種習慣後,就愈剪愈多字,後來買了一個櫃子,按字母排列,專門分放剪下的字。她出版的詩集中,有一本是羅馬尼 亞語,那是朋友寄羅馬尼亞的印刷品給她剪,她剪了兩年,才完成詩集。

剪貼房變成大工具房,她不寫長篇時,剪貼是最喜歡的嗜好,是很密集的文 字工作。作家朋友們也會從各地寄專有名詞的廣告給她,她將喜歡的排列組合成明信片大小,內容通常要思考很久,不管是顏色、形狀、圖案都要講究,一張明信片 的完成大約要一星期,可以不眠不休地做,詩的排列確定了,才貼上明信片。若一行字太多,就把介詞變小,拼字時,很注意詩的韻律,為了配合韻律,找字的過 程,常常整首詩就會走到不同方向,有時發明一些組合字,自己很喜歡,但因韻律關係而排不進詩裡,就拿掉,但又一直記得那個字,只好重頭組詩。她說做這些剪 貼工作真是欲罷不能,她還指指自己的背脊,表示因為樂在其中而坐太久,把背都坐僵了。她談論剪貼詩,不時發出笑聲,簡直是比寫小說還快樂的事。

鴻 鴻給她看他在波蘭拍到的她的拼貼詩譯本,她頗有感慨地表示,一些東歐人,比如波蘭,對美感很敏銳,但在極權下被壓抑了,她詩集的波蘭文和荷蘭文版都翻譯得 很好,也受歡迎,甚至有位據稱得癌的年輕人,趕在生命終止前翻譯她的拼貼詩集。她在二十幾年前就開始做拼貼詩,那時出版,沒人注意,現在大家注意到她的拼 貼詩了。

我問,她詩集上的圖案也是自己設計的嗎?她說也是自己從雜誌上剪下來貼出配合詩意的圖形。這樣說來,慕勒的才華又涉及美術了,她的拼圖饒富趣味,簡單的線條和顏色就蘊含了意義,我看到那些圖,直覺上和黃春明的撕紙畫聯想在一起。都是作家不可掩抑的藝術才華。

鴻鴻也有他的聯想,他因此介紹台灣詩人夏宇曾將自己的整本詩集剪開,重新拼貼,她用此方式打破自己的創作習慣,《現在詩》的詩人們也做另一個練習,就是拿份報紙或雜誌文章,把不要的字塗掉,剩下的就是一首詩,這應是另一種方式的拼貼。

題材不是作家自己選擇的 是題材主宰作家

離 約定的採訪時間逐漸靠近,我趕緊又問她,在《呼吸鞦韆》的文末寫到「自從我返鄉之後,我寶貝上的字樣不再是『我在這裡』,也不是『我到過那裡』,我寶貝上 的句子是『我離不開那裡』」,這些敘述是否也相當表示了她在羅馬尼亞的經驗,會是她持續的寫作內容?這個問題一出,她的眼裡馬上出現冷靜近乎哀傷的神色, 和剛才眉飛色舞談剪貼詩判若兩人,她以平穩的聲音回答說,有過極端經歷的人幾乎總是如此,像是經歷過戰爭的人,面臨過生命威脅的人,許多勞役營和集中營的 人變成作家,即是因為如此;深刻的內心傷害難斷,文學總會走向人生最沉重之處,文學題材不是作家選擇的,而是作家不得不處理該問題,是題材主宰作家;受傷 最重之處,反而成了寶藏/寶貝。理論上「寶藏」應是美好和極具價值的,然而文中的寶藏/寶貝,指的則是傷痕與破壞。《呼吸鞦韆》中提供寫作材料的帕斯提歐 爾,臨死前不斷夢到勞役營的經驗;很多國家現在仍有勞役營,我不敢想像那裡的狀況。寫作是一種療傷的方式,不寫作的人,一生都將抱著傷痛度過餘生。

為 了更明白作家的自我定位和想法,我提問在她得諾獎時,有報導指她是德國文學的邊緣人,她的書寫是一種邊緣文學,她如何看待這種說法。她沉默,聳聳肩,然後 說,她的題材由她自己作主,她的題材來自她的人生,德國曾有兩個極權統治經驗,一個是第三帝國,一個是東德極權,她寫的題材是極權專政,所以人們怎麼能說 她的作品是邊緣文學呢?說她是文學邊緣人的人,必然對文學缺乏概念。她的回答簡短而肯定,也一致獲得我們在場者的尊敬。

她也關心艾未未事件在台灣受注意的程度,以及中國六四之後,中國對異議分子的限制是更嚴或較鬆。

我接著問,她的文學養成是在羅馬尼亞,當時她閱讀書籍有沒有受到限制?她說她從羅馬尼亞的歌德學院取得書籍,在學院的圖書館她可以自由閱讀,或朋友從國外帶回來。

鴻鴻邀請她可不可能出席台灣的詩歌節,她說自得到諾獎以來,這一年半來,她的行程繁忙,她沒有欲望呈現自己,也無意不斷透過訪談談自己的作品,但很多出版她作品的國外出版商邀請她到該國,但她只有一個人,無法一一答應,無論如何,目前已排不出時間,也許等以後得空。

從訪談的互動中,可看出慕勒是位有原則、能堅持並主張想法的人,但她待人相當熱誠,也想滿足他人的需求,如我們的提問及邀請。在整個訪談過程,她的回答充滿表情,不吝於表現她的喜怒。

在 訪談的前半段,除了進來時,手上已夾一支菸外,她又連抽了兩支,加上不斷講話,訪談結束時,她咳了幾聲,我問她要再加點水嗎?因為她的杯子已空了。她說不 必,倒是看到我杯中的薑汁檸檬茶還八分滿,提醒我把飲料喝完,這飲料還是她推薦我們喝的,她笑稱可預防德國正流行的腸病毒。這個提醒讓我感受到她的細心和 待人的誠懇,即便採訪對她已是一種負擔,她一旦答應便儘量地體貼採訪者。她堅持由她付飲料費,將我們當客人招待。我們有幸在占用了她一個多小時的時間裡, 感受她的談話內容與她的性情,那是文字閱讀外,更多的慕勒,更多的理解。她不再是書封上的一個名字,而是心上的一個深刻人影。(此篇訪談,現場以中英德語 進行,內文以發問順序整理,特別感謝胡昌智先生的現場德語翻譯,及全程在場的唐薇小姐對本文的校閱,由於他們,訪談內容得以精準。) ●

Yiwu Liao 分享了 1 則動態回顧。

其他 2 人。

Herta Müller Wins Nobel Prize in Literature

Herta Müller, the Romanian-born German novelist and essayist who writes of the oppression of dictatorship in her native country and the unmoored existence of the political exile, won the 2009 Nobel Prize in Literature on Thursday.

Herta Müller, 56, emigrated to Germany in 1987 from her native Romania.

Announcing the award in Stockholm, the Swedish Academy described Ms. Müller as a writer “who, with the concentration of poetry and the frankness of prose, depicts the landscape of the dispossessed.” Her award coincides with the 20th anniversary of the fall of Communism in Europe.

Ms. Müller, 56, emigrated to Germany in 1987 after years of persecution and censorship in Romania. She is the first German writer to win the Nobel in literature since Günter Grass in 1999 and the 13th winner writing in German since the prize was first given in 1901. She is the 12th woman to capture the literature prize. But unlike previous winners like Doris Lessing and V. S. Naipaul, Ms. Müller is a relative unknown outside of literary circles in Germany.

She has written some 20 books, but just 5 have been translated into English, including the novels “The Land of Green Plums” and “The Appointment.”

At a packed news conference on Thursday at the German Publishers & Booksellers Association in Berlin, where she lives, Ms. Müller, petite, wearing all black and sitting on a leopard-print chair, appeared overwhelmed by all the cameras in her face. She spoke of the 30 years she spent under a dictatorship and of friends who did not survive, describing living “every day with the fear in the morning that in the evening one would no longer exist.”

When asked what it meant that her name would now be mentioned in the same breath as German greats like Thomas Mann and Heinrich Böll, Ms. Müller remained philosophical. “I am now nothing better and I’m nothing worse,” she said, adding: “My inner thing is writing. That I can hold on to.”

Earlier in the day, at a news conference in Stockholm, Peter Englund, permanent secretary of the Swedish Academy, said Ms. Müller was honored for her “very, very distinct special language” and because “she has really a story to tell about growing up in a dictatorship ... and growing up as a stranger in your own family.”

Just two days before the announcement, Mr. Englund criticized the jury panel as being too “Eurocentric.” Europeans have won 9 of the past 10 literature prizes. On Thursday Mr. Englund told The Associated Press that it was easier for Europeans to relate to European literature. “It’s the result of psychological bias that we really try to be aware of,” he said.

Ms. Müller was born and raised in the German-speaking town of Nitzkydorf, Romania. Her father served in the Waffen-SS in World War II, and her mother was deported to a work camp in the Soviet Union in 1945. At university, Ms. Müller opposed the regime of Nicolae Ceausescu and joined Aktionsgruppe Banat, a group of dissident writers who sought freedom of speech.

She wrote her first collection of short stories in 1982 while working as a translator for a factory. The stories were censored by the Romanian authorities, and Ms. Müller was fired from the factory after refusing to work with the Securitate secret police. The uncensored manuscript of “Niederungen” — or “Nadirs” — was published in Germany two years later to critical acclaim.

“Niederungen” and other early works depicted life in a village and the repression its residents faced. Her later novels, including “The Land of Green Plums” and “The Appointment,” approach allegory in their graphic portrayals of the brutality suffered by modest people living under totalitarianism. Her most recent novel, “Atemschaukel,” is a finalist for the German Book Prize.

Even in Germany, Ms. Müller is not well known. “She’s not one of these public trumpeters — or drum-beaters, like Grass,” said Volker Weidermann, a book critic for the Frankfurter Allgemeine Sunday newspaper. “She’s more reserved.”

Ms. Müller also has a low profile in the English-speaking world, although “The Land of Green Plums” won the International Dublin Impac Literary Award in 1998.

Writing in The New York Times Book Review in 2001, Peter Filkins described “The Appointment” as using the thuggery of the government as “a backdrop to the brutality and betrayal with which people treat one another in their everyday lives.”

Lyn Marven, a lecturer in German studies at the University of Liverpool who has written about Ms. Müller, said: “It’s an odd disjunction to write about traumatic experiences living under a dictatorship in a very poetic style. It’s not what we expect, certainly.”

Michael Naumann, Germany’s former culture minister and the former head of Metropolitan Books, one of Ms. Müller’s publishers in the United States, praised her work but said she was “not a public intellectual.”

She has, however, spoken out against oppression and collaboration. In Germany, for example, she has criticized those East German writers who worked with the secret police.

A spokeswoman for Metropolitan, a unit of Macmillan that released English translations of “The Land of Green Plums” and “The Appointment” in the United States, said the publisher would reissue hardcover editions of those books. Northwestern University Press, which published the paperback version of “The Land of Green Plums,” said it was reprinting 20,000 copies.

In Germany, Ms. Müller’s publisher, Carl Hanser Verlag, was also scrambling to reprint more copies of “Atemschaukel,” as well as other titles from her backlist. Asked whether winning the prize while relatively young could hurt her work, Ms. Müller said: “I thought after every book, never again, it’s my last. Then two years pass, and I start writing again. It doesn’t feel any different after I’ve won this prize.”

The awards ceremony is planned for Dec. 10 in Stockholm. As the winner, Ms. Müller will receive 10 million Swedish kronor, or about $1.4 million.

文化社会 | 2009.10.11

赫塔·米勒和她的罗马尼亚

一个作家可以把苦难直接转化成文学作品,不加柔化,不予中和。这是赫塔·米勒每一本书都证明了的,无论是在罗马尼亚写就的,还是移民德国后 创作的。她的美学感觉具有地震仪般的准确性,她非同寻常的文学天才从一开始就有了固有的定义。赫塔·米勒的正义感,她那不可动摇的道德直线,她对一切形式 迫害与愚蠢行为的绝不宽容,使她成为共产党秘密情报机构眼里的可疑对象。

今年诺贝尔文学奖的这位女得主在大学时代就非常接近罗马尼亚德语作家行动团体Banat。理查德·瓦格纳也是这个圈子的成员。虽然这个团体刚开始时 是非政治性的,但他们的成员受到秘密情工机构的迫害,有些成员甚至被逮捕。在赫塔·米勒拒绝合作之后,罗马尼亚秘密情工机构不断地威胁着她。尽管情工机构 对她施加了种种刁难、陷害和恐吓,她始终忠于自己的原则,甚至冒着生命危险。

1987年2月赫塔·米勒移民德国,在德国继续她的文学创作。她的所有作品都能让人感觉到那未能愈合的创伤,即使有时候这种痕迹隐藏在文字的最深处。

她的长篇小说、杂文,甚至她那些在最近22年里在德国写就的拼贴诗,都以最高水平的美学素质向西方展示独裁政权下的可怕日子。赫塔·米勒与罗马尼亚 的联系不仅仅体现在那"永不消逝的过去"上,而且也铭刻在语言之中。罗马尼亚语言在她的文字里出现,并经常通过具有独特表现力的比喻和语句放射光芒。

1989年后,赫塔·米勒经常回罗马尼亚参加各种文化活动。她的长篇小说大部分现在已经译成罗马尼亚语。她从来没有停止过对公众讲真话,无论在哪个国家。

这在她最新的长篇小说《呼吸钟摆》中再次得到证实。这是一部以风格全新的、文学色彩浓郁的笔墨描述独裁政权和意识形态造成的苦难的小说。

作者:Rodica Binder / 平心

责编:达杨

德女作家慕勒 獲諾貝爾文學獎

〔編 譯張沛元/綜合八日外電報導〕向來是諾貝爾文學獎得主熱門人選的德國女作家荷塔.慕勒,八日摘下二○○九年諾貝爾文學獎桂冠,成為第十二位獲得此一殊榮的 女文豪。生於羅馬尼亞的慕勒過去批評共產政權不遺餘力,被譽為是羅馬尼亞文學良心,在柏林圍牆倒下二十週年之際,她的獲獎被視為諾貝爾獎對共產主義垮台的 肯定。

破紀錄!今年已有四女性獲獎

慕勒也是今年諾貝爾獎頒發至今第四位獲獎的女性,為該獎自一九○一年首度頒發以來、女性得獎人數最多的一年。今年的諾貝爾獎迄今已頒發醫學、物理、化學與文學獎,其中醫學獎有兩名女性獲獎,化學獎與文學獎各有一名女性得獎。

瑞典學院在頌詞讚揚慕勒的作品,「有詩歌的精練,散文的率直,描述無家可歸者之境況」。現年五十六歲的慕勒對於獲獎深表震驚,「我很驚訝,還不太敢相信,我現在不知道該說什麼。」

瑞典學院秘書長英格朗表示,慕勒的作品風格極為獨特,這一方面源自於她身為被起訴的羅馬尼亞異議人士的背景,一方面也基於她在自己的國家,對政治體制、對主流語言以及對自己的家庭的異鄉人身分。慕勒將可獲得一千萬瑞典克朗(約台幣四千五百九十四萬兩千元)的獎金。

慕 勒於一九八二年在文壇初試啼聲,發表短篇故事集「低地深淵」(Niederungen),但隨即遭當時共黨政府審查刪修。一九八四年,慕勒在德國出版完整 版,同年又在羅馬尼亞出版「受壓迫的探戈」。這兩本書都是描述一個羅馬尼亞的德語小村莊在貪瀆、偏執與壓迫下的艱苦生活,「羅馬尼亞國營媒體痛批這些作 品,但在羅馬尼亞以外,德國媒體卻對這兩本書予以好評,」瑞典學院說。

慕勒向來公開批判羅馬尼亞獨裁者西奧塞古的共產政權與秘密警察,曾因 拒絕當線民而丟了畢生第一份工作,最後被禁止在羅馬尼亞出版作品;一九八七年,慕勒與同為作家的夫婿移居德國,稍後陸續出版「狐狸當時已經是獵人」(一九 九二)、「風中綠李」(一九九四),以及「約定」(二○○一)等小說,皆詳盡刻畫在停滯腐敗的獨裁政權統治下的日常生活。慕勒的著作多以德文為主,但有部 份作品被翻譯為英文、法文與西班牙文。

慕勒的父親在二戰時曾參與納粹黨衛軍。許多德裔羅馬尼亞人在一九四五年被遣返至蘇聯,慕勒的母親也不 例外,在勞改營待了五年。多年後,慕勒在作品「Atemschaukel」中描述德裔羅馬尼亞人流亡蘇聯的故事。慕勒曾在德、英與美等地許多高等學府客座 講學,目前定居柏林。

沒有留言:

張貼留言