*主管半導體部門的副總裁道森被調到公司總部管理「行政」(總公司人事、新工程、庶務等),這是另一個不重要的職務,明顯的貶職,當天道森就打包走人。

*彪希晉陞為集團副總裁,原來主管行銷的助理副總裁,被換下來,但無別的職務給他,等於要他走人,他也完全瞭解這個訊息,也立刻辭職。

這是職場文化的一部分,美國社會有,台灣社會也有同樣的現象,最大的不同是當事人的反應。美國人往往會馬上走人了事,彼此不必勉強在一起;台灣人通常逆來順受,隱忍為五斗米折腰。

柳宗悅的民藝觀

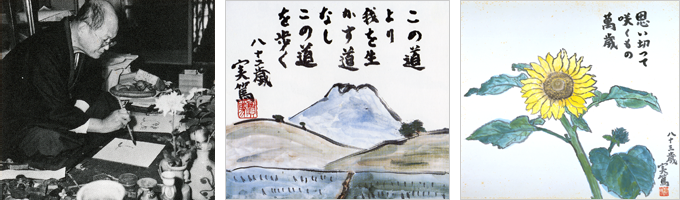

武者小路 実篤:実篤の生涯;森 木;《維摩經》/『梵漢和対照・現代語訳 「維摩経」』一步一步 情人節巧克力禮盒This year, the creations of chocolatiers are inspired by the timeless elegance of Art Deco, an artistic movement that emerged in the 1920s, ...

| 梵漢和対照・現代語訳 維摩経 販売元:岩波書店 Amazon.co.jpで詳細を確認する |

Mexico had an extended deadline for a trade deal.Credit...Sandy Huffaker/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

Mexico had an extended deadline for a trade deal.Credit...Sandy Huffaker/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

人工智慧研究人員的就業市場長期以來與職業運動市場相似。 2012年,多倫多大學的三位學者發表了一篇研究論文,描述了一個能夠識別花朵和汽車等物體的開創性人工智慧系統。之後,他們以4400萬美元的價格將自己拍賣給了出價最高的企業——Google。

這引發了整個科技業的人才爭奪戰。到2014年,微軟研究主管彼得李(Peter Lee)將這個市場比作新興職業橄欖球運動員的市場,其中許多人的年薪約為100萬美元。

A.I. Researchers Are Negotiating $250 Million Pay Packages. Just Like N.B.A. Stars.

A.I. technologists are approaching the job market as if they were Steph Curry or LeBron James, seeking advice from their entourages and playing hardball with the highest bidders.

紀念安迪・葛洛夫(Andrew Grove) 鍾漢清 2016-03-27

中國沙漠中建DATA CENTERS 202507

紐約不完全攻略手冊 2024.12

紐約時報 訃聞版,科學版……

data centers, museums 董 書法, galleries,

----

2025年特朗普就職典禮的籌款有望創造歷史紀錄。包括高盛、

TI

華盛頓州馬拉加的住宅和農田景觀,微軟正在那裡開發一個資料中心。

Wenatchee | |

|---|---|

| City of Wenatchee | |

View over the city in 2009 | |

| Nickname: Apple Capital of the World | |

| |

Coordinates:  47°28′24″N 120°19′20″W 47°28′24″N 120°19′20″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Washington |

| County | Chelan |

| Established | 1892 |

| Incorporated | February 29, 1892 |

| Named for | Wenatchi tribe |

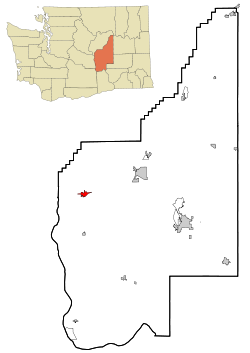

Malaga, Washington | |

|---|---|

Malaga

山谷景觀,河流和兩條鐵軌穿過中心。

華盛頓州馬拉加的住宅和農田景觀,微軟正在那裡開發一個資料中心。

人工智慧、電工和華盛頓中部的新興城鎮

隨著來自全國各地的電工將科技業新的巨型資料中心連接到其充足的電力供應,農村地區正在迅速變化。

華盛頓州馬拉加的住宅和農田景觀,微軟正在那裡開發一個資料中心。

The rural region is changing fast as electricians from around the country plug the tech industry’s new, giant data centers into its ample power supply.

A view of homes and farmland in Malaga, Wash., where Microsoft is developing a data center.

Quincy, Washington | |

|---|---|

| |

| Motto(s): Where Agriculture Meets Technology Motto: Opportunities Unlimited | |

Location of Quincy, Washington | |

Coordinates:  47°14′1″N 119°51′8″W 47°14′1″N 119°51′8″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Washington |

| County | Grant |

Quincy High School is a public high school serving 770 students in grades 9–12 located in Quincy, Washington, United States.

Quincy High School is ranked 230-308th within Washington. The total minority enrollment is 89%, and 87% of students are economically disadvantaged.

Quincy High is known for its Career and Technical Education programs that include:

Quincy High was recognized in 2012, by the Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, for efforts that have significantly reduced the achievement gap[4] in test scores for underserved populations.

昆西高中以其職業和技術教育課程而聞名,其中包括:

商業與行銷

烹飪藝術

紡織藝術

美國手語

影片製作

預工程

建造

消防科學

2012 年,昆西高中因大幅縮小服務不足人口的考試成績差距[4]而受到華盛頓州公共教育總監辦公室的認可。

Over time, Mr. Nickell found his way, and community. He went to his first brotherhood night at a bar in Indiana, and learned the rules of the road: Put in eight hours of work for eight hours of pay, no more, no less. Do not be a pushover on safety, and do not do more than you’re paid for, lest you be considered “wormy.”

隨著時間的推移,尼克爾先生找到了自己的道路和社區。他在印第安納州的一家酒吧參加了他的第一個兄弟會之夜,並了解了交通規則:工作八小時,拿八小時工資,不多也不少。不要在安全問題上屈服,也不要做超出報酬的事情,以免被認為是「蠕蟲」。

著名的小說就叫"Howard's End"(中文譯本叫做《綠苑春濃》,聯經,1992;

《此情可問天》,業強,1992),書名中的Howard是姓氏,End是宅第的名稱,通常位置在一條街道的盡頭, ...

Hub & Store. William S. Burroughs. I am a snake and a tiptoe feather at opposite ends of the scales as they balance themselves against each other.

William Seward Burroughs II (/ˈbʌroʊz/; February 5, 1914 – August 2, 1997) was an American writer and visual artist. He is widely considered a primary figure of the Beat Generation and a major postmodern author who influenced popular culture and literature.[2][3][4] Burroughs wrote 18 novels and novellas, six collections of short stories, and four collections of essays. Five books of his interviews and correspondences have also been published. He was initially briefly known by the pen name William Lee. He also collaborated on projects and recordings with numerous performers and musicians, made many appearances in films, and created and exhibited thousands of visual artworks, including his celebrated "shotgun art".[5]

Burroughs was born into a wealthy family in St. Louis, Missouri. He was a grandson of inventor William Seward Burroughs I, who founded the Burroughs Corporation, and a nephew of public relations manager Ivy Lee.

Burroughs attended Harvard University, where he studied English, then anthropology as a postgraduate, and went on to medical school in Vienna. In 1942, he enlisted in the U.S. Army to serve during World War II. After being turned down by both the Office of Strategic Services and the Navy, he veered into substance abuse, beginning with morphine and developing a heroin addiction that would affect him for the rest of his life.

In 1943, while living in New York City, he befriended Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac. This liaison would become the foundation of the Beat Generation, later a defining influence on the 1960s counterculture.

Burroughs found success with his confessional first novel, Junkie (1953), but is perhaps best known for his third novel, Naked Lunch (1959). It became the subject of one of the last major literary censorship cases in the United States after its US publisher, Grove Press, was sued for violating a Massachusetts obscenity statute.

Burroughs is believed to have killed his second wife, Joan Vollmer, in 1951 in Mexico City. He initially claimed that he had accidentally shot her while drunkenly attempting a "William Tell" stunt.[6] He later told investigators that he had been showing his pistol to friends when it fell and hit the table, firing the bullet that killed Vollmer.[7] After he fled Mexico back to the United States, he was convicted of manslaughter in absentia and received a two-year suspended sentence.

Much of Burroughs' work is highly experimental and features unreliable narrators, but it is also semi-autobiographical, often drawing from his experiences as a heroin addict. He lived at various times in Mexico City, London, Paris, and the Tangier International Zone in Morocco, and traveled in the Amazon rainforest — and featured these places in many of his novels and stories. With Brion Gysin, Burroughs popularized the cut-up, an aleatory literary technique, featuring heavily in such works of his as The Nova Trilogy (1961–1964). His writing also engages frequent mystical, occult, or otherwise magical themes, constant preoccupations in both his fiction and real life.[4][8]

In 1983, Burroughs was elected to the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters. In 1984, he was awarded the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by France.[9] Jack Kerouac called Burroughs the "greatest satirical writer since Jonathan Swift";[10] he owed this reputation to his "lifelong subversion"[11] of the moral, political, and economic systems of modern American society, articulated in often darkly humorous sardonicism. J. G. Ballard considered Burroughs to be "the most important writer to emerge since the Second World War," while Norman Mailer declared him "the only American writer who may be conceivably possessed by genius."[10]

wormy

(一個人)軟弱、卑鄙或令人厭惡的。

“你這個黏蟲蟲!”