How Much Do You Know About Your Dreams?

您對自己的夢想了解多少?

科學家們並不確定我們為什麼會做夢,但他們提出了許多理論。我們每晚的冒險可以幫助我們排練威脅情況、處理情緒和處理資訊。但是,儘管存在所有未知數,但研究人員確實知道很多事情,其中一些可能會讓您感到驚訝。

Scientists aren’t exactly sure why we dream, but they’ve put forth many theories. Our nightly adventures may help us rehearse threatening situations, work through emotions and process information. But, for all of the unknowns, there is plenty that researchers do know — and some of it may surprise you.Does Sigmund Freud still matter? (Jane Ciabattari): Mapping The Psychoanalytic Movement文學仍然受到佛洛伊德思想的強烈影響。. Anna Freud 傳記有中文版

Psychoanalytic Filiations: Mapping The Psychoanalytic Movement

How does one write the history of the psychoanalytic movement? This...

EVENTBRITE.CO.UK

google:佛洛伊德去世 75? 年來,精神分析理論發生了很大變化,但文學仍然受到佛洛伊德思想的強烈影響。

佛洛伊德的失誤。俄狄浦斯情結。自我。身分證字號。超我。西格蒙德‧佛洛伊德的著作改變了我們對人類行為的看法。這位精神分析學的創始人開創了對也許最初不可靠的敘述者——自我——的洞察,並開闢了通往日益複雜的文學人物的道路,其動機超出了顯而易見的程度。

佛洛伊德在1899 年出版的里程碑式的著作《夢的解析》中寫道:「每個夢都會以一種心理結構的形式展現出來,充滿意義,並且可以在清醒狀態的心理活動中被被分配到一個特定的位置。他借鑒索福克勒斯、歌德的《浮士德》和莎士比亞——尤其是哈姆雷特、李爾王和馬克白——來闡述他對無意識動機以及夢的複雜隱喻和位移的理解。他用詩人和小說家的語言來概述非理性行為,開創了我們認為司空見慣的概念。

要了解佛洛伊德對當今文學的持久影響,追溯他的著作與同時代文學作品之間的相似之處是很有啟發性的。

同儕壓力與讚揚

佛洛伊德在寫給阿瑟‧施尼茨勒(Arthur Schnitzler) 的信中寫道:「當我讀到你的一部優美作品時,我不斷地在小說背後找到與我自己的想法相似的命題、興趣與解決方案。施尼茨勒和佛洛伊德一樣,在維也納接受了神經科醫生訓練。他對《夢的解析》也很熟悉。施尼茲勒的小說包括夢、佛洛伊德符號(山、湖)和意識流,以佛洛伊德在癔症研究(1895)中所描述的「自由聯想」為藍本。

佛洛伊德也與奧地利小說家斯特凡‧茨威格(Stefan Zweig) 通信,茨威格在1931 年關於這位精神分析學家的傳記文章中指出,「二十年前,弗洛伊德的思想仍然被認為是褻瀆神靈和異端。如今,它們可以自由流通,並在日常語言用法中找到表達方式。

佛洛伊德的精神分析理論和對無意識的強調塑造了數十年的衝突人物。他的俄狄浦斯情結理論為許多文學作品奠定了基礎,從 DH 勞倫斯 1913 年的小說《兒子與情人》中保羅·莫雷爾和他母親之間的亂倫關係到現在.... BETWEEN THE LINES| 22 April 2014

Does Sigmund Freud still matter?

Jane Ciabattari

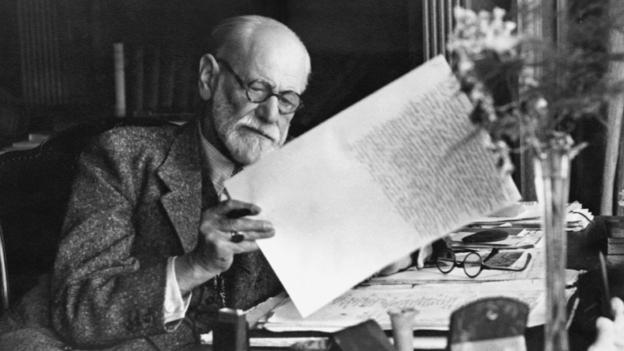

Sigmund Freud in 1920 (Corbis)

Psychoanalytic theory has changed a lot in the 75 years since his death, but literature still feels the strong influence of Freud's ideas, argues Jane Ciabattari.

Freudian slips. The Oedipus complex. The ego. The id. The superego. Sigmund Freud’s writings changed how we perceive human behaviour. The founder of psychoanalysis pioneered insights into perhaps the original unreliable narrator – the self – and opened the pathway toward increasingly complex literary characters with motives beyond the obvious.

“Every dream will reveal itself as a psychological structure, full of significance, and one which may be assigned to a specific place in the psychic activities of the waking state,” Freud wrote in his landmark book, The Interpretation of Dreams, published in 1899. From the beginning, his work was intertwined with the canonical literature of his time. He drew upon Sophocles, Goethe’s Faust and Shakespeare – especially Hamlet, King Lear and Macbeth – to explicate his understanding of unconscious motivations and the complex metaphors and displacements of dreams. He used the language of poets and novelists to outline irrational behaviour, pioneering concepts we have come to think of as commonplace.

To begin to understand Freud’s enduring impact on literature today, it is illuminating to trace the parallels between his writings and the work of his literary contemporaries.

Peer pressure and praise

“When I read one of your beautiful works I keep finding, behind the fiction, the same propositions, interests and solutions that are familiar to me from my own thoughts,” Freud wrote to Arthur Schnitzler, whose sexually explicit work, including the 1897 play Reigen (best known as La Ronde) was banned in Austria for nearly a quarter century. Schnitzler was, like Freud, trained as a neurologist in Vienna. And he was familiar with The Interpretation of Dreams. Schnitzler’s fiction includes dreams, Freudian symbols (mountains, lakes) and stream-of-consciousness, modelled on the “free association” Freud describes in Studies on Hysteria (1895).

Freud also corresponded with Austrian novelist Stefan Zweig, who noted in his 1931 biographical essay about the psychoanalyst, “Twenty years ago, Freud’s ideas were still thought of as blasphemous and heretical. Today they circulate freely and find expression in ordinary linguistic usage.”

Freud’s psychoanalytic theories and emphasis on the unconscious have shaped decades of conflicted characters. His theory of the Oedipus complex underpins many a literary work, from the incestuous relationship between Paul Morel and his mother in DH Lawrence’s 1913 novel Sons and Lovers to the present.

Freud’s work with traumatised World War I soldiers led to Beyond the Pleasure Principle, which fed into the character of Septimus Smith in Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway (1925). The modernist poet HD sought out Freud in 1933 when she was suffering from writer’s block, triggered in part by her dread of another devastating world war. Her 1956 book, Tribute to Freud, is a memoir of her psychoanalytic treatment.

Critical analysis

Freud’s theories also have inspired literary critics for more than a century.

In the 1940s, Lionel Trilling noted the “poetic quality” of Freud’s principles, which, he wrote, descended from “classic tragic realism… a view which does not narrow and simplify the human world for the artist, but, on the contrary, opens and complicates it”.

Postmodernism, Structuralism and Post-Structuralism – including the work of French theorists Claude Levi-Strauss, Roland Barthes, Jacques Lacan, Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Gilles Deleuze and Julia Kristeva – all have roots in Freud’s thinking.

Susan Sontag argued against Freud and for an “erotics of art” in her 1964 essay Against Interpretation. Harold Bloom applied Freud’s Oedipus complex to rivalries among poets and their precursors in his The Anxiety of Influence (1973), an approach given a feminist slant by Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar in Forward into the Past: The Complex Female Affiliation Complex (1985). Peter Brooks mined Freud’s dream-work for ideas of how novels are plotted in Reading for the Plot (1992).

Freud’s influence continues in the 21st Century. But today he is as likely to turn up as a character as a theoretical catalyst. Recently we’ve seen postmodern feminist novels such as the European Union Award-winningFreud’s Sister by Goce Smilevski, translated from the Macedonian by Christina E Kramer (2012). This novel fictionalises the melancholy tale of Freud’s youngest sister Adolfina, who perished in the Theresienstadt concentration camp (four of Freud’s five younger sisters died in the Nazi death camps). Karen Mack and Jennifer Kaufman’s historical romance Freud’s Mistress (2013) spins a tale out of Freud’s alleged affair with Minna, his wife Martha’s younger sister. The producers of Downton Abbey have a TV series in the works called Freud: The Secret Casebook, set in fin de siècle Vienna, positing Freud as the first “profiler”, and delving into his own “tangled and provocative personal life”, Variety reported April 16.

Mental detective

Freud’s case studies, crafted as stories or novellas, have yielded endless bounty for fiction writers. The studies are rich texts to be questioned, critiqued, studied, imitated, modified and fictionalised.

One of Freud’s best known case studies, described in his 1905 Dora: An Analysis of a Case of Hysteria, involves a young woman with limb pains and a hysterical loss of voice, whose symptoms Freud sees as displacements of sexual feelings rooted in childhood memories. Lidia Yuknavitch’s edgy 2012 novel Dora: A Headcase, places Dora – whose real name was Ida Bauer – in contemporary Seattle with an analyst she calls Siggy. “I first read Freud’s famous case study on hysteria based on his client Ida Bauer when I was in my 20s,” Yuknavitch told The Rumpus. “It pissed me off so badly it haunted me for 25 years. But I had to wait to be a good enough writer to give Ida her voice back.”

The Dora case is also the basis of Sheila Kohler’s new novel Dreaming for Freud. A beautiful 17-year-old patient is taken to Freud by her father. “He wants her to be more reasonable,” says Kohler. “He wants her to have an affair with his mistress’s husband, but not to speak of it. She protests and she says the man has been after her since she was thirteen.” The girl finds Interpretation of Dreams in her father’s library and decides to invent dreams to bring to Freud, feeding him fabrications in their sessions that appear in his later case study.

“Freud’s case studies are all written as mysteries, like Conan Doyle,” says Kohler, who has been teaching a class called Reading Freud's Great Case Histories as Short Stories at Princeton University this spring. “Each case study is a mystery. Each one he solves. Is he right? It doesn’t really matter.”

This mystery may, in the end, be the point.

From his first publications, Freud’s ideas were revolutionary and controversial. His followers – Carl Jung, Otto Rank, Alfred Adler, Karen Horney, Anna Freud, Melanie Klein and Erik Erikson among them – diverged from his original blueprint, extending and modifying psychoanalytic thought and practice to this day.

Freud the author, awarded the 1930 Goethe prize for literature for his “clear and impeccable style”, catalyst for innumerable other writers, may be as important as Freud the scientist. The highest measure of his meaning may derive from the echoes of his voice in artistic work.

---

Anna Freud was the youngest of Sigmund Freud's children, and grew up to be a founding legend in the field of Child psychoanalysis.

As a child, Anna was relentlessly competitive with her siblings, most especially her sister Sophie Freud. Anna had the brains, but Sophie had the beauty, and therefore Anna had an "age-old jealousy of Sophie." Anna was frequently sent to health farms for much-needed rest, calm walks and proper eating to fill in her slender frame.

Although Anna's relationship with her siblings was difficult, she and her father were very close. She later claimed that she learned more from her father and his friends than she ever did through formal schooling. In fact, this is how Anna learned Hebrew, French, German, English and Italian. She was only 15 years old when she first read her father's work, which would be instrumental in her career.

Ever the proud father, it is said that Sigmund Freud wrote more of Anna in his diaries than any other member of the family.

沒有留言:

張貼留言