【尼采與生命:一部新的哲學史】

芭芭拉•斯蒂格勒 著

目錄

導言 電報時代的生命與生者

第一部分 現代形而上學的屏障

第一章 第一屏障:笛卡爾的自我

第二章 第二屏障:康德的先驗主體

第三章 第三屏障:叔本華的身體

第四章 最後屏障:歷史哲學中的進化論

第二部分 尼采與生物學

第五章 以生物學思考生命

第六章 從身體與生理學出發:為何?

第七章 作為生命的權力意志,即記憶

第八章 生命的偉大政治

第三部分 後尼采時代:論爭與承接

第九章 進化與民主:尼采與美國實用主義

第十章 流變與現實:尼采與柏格森主義

第十一章 健康、醫學與規範性:康吉萊姆——“無證尼采主義者”

第十二章 超越自然主義與建構主義:尼采、福柯與當代生物學

尼采與生命:一部新的哲學史

結論 尼采:後真理時代的哲學家?

——生態與衛生危機時代的生命知識、科學與真理

附錄

致謝

本書寫作緣起說明

索引

----

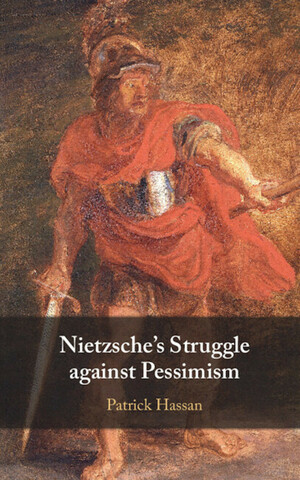

談尼采 受苦的人沒有悲觀的權利 2025漢清講堂2018 張旺山教授和我分別有影片討論《悲劇的誕生》.Nietzsche’s Struggle Against Pessimism.....。 2013《這個朝露世界》(This world of dew).小林一茶(Kobayashi Issa),達賴喇嘛及繼承人,受苦的價值 (Pico Iyer )“The Man Within My Head,”

這引申出:"外交人員沒 有悲觀的權利" 或"台灣人沒有悲觀的權利"等等說法。我74歲2025了,要探究尼采這句箴言的確切意義,

請問Google,說尼采的《悲劇的誕生》中的觀點,這很惱人,因為2018年

後來我讀了2023年劍橋大學出版社.Nietzsche’s Struggle Against Pessimism.....的書評。 知道這是19世紀德國哲學界的討論主題之一。

獨後,自己想想 我要如何處理這問題。

https://ndpr.nd.edu/reviews/nietzsches-struggle-against-pessimism/#:~:text=As%20Hassan%20puts%20it%2C%20the,Pessimism%20ceases%20to%20be%20ourproblem.

Nietzsche’s Struggle Against Pessimism

2013

觀點

生活就是受苦受難

皮柯·耶爾 2013年09月12日

Daehyun Kim

日本奈良——數百名敘利亞人看來已被化學武器殺死,保護其

他人免遭同樣厄運的嘗試則對更多人的生命構成威脅。一名8歲兒童在波士頓被炸彈炸死,一個月之後,一名兒童和她的母親在奧克拉荷馬州的颶風中喪生。失控的

火車在原本平靜的加拿大和西班牙分別奪走了數十人的生命。在巴格達,一系列以冰激凌店、公交車站和知名餐館為目標的合謀爆炸事件,至少殺死了46人。無窮

盡的苦難可曾減輕過?人們能從苦難中尋找到任何意義嗎?

每種文化傳統中的智者都對我們說,苦難會帶來領悟和啟迪;

對佛陀來說,苦難是人生的第一法則,至少一些苦難源於我們自己的執迷不悟(比如心懷自我),在這些情況下,消除苦難的方式也存在於我們的心靈深處。所以,

在某些情況下,苦難也許既是我們太把自己當回事兒的原因,也是其結果。我曾在日本遇到過一位90多歲的修禪畫家,他對我說,受苦是一種特權,受苦讓我們趨

向思考本質性的東西,讓我們擺脫短視的自滿情緒;他說,當他還是孩子時,人們認為一個人應該花錢買苦受,因為受苦是一種隱藏的祝福。

然而,所有這些觀點根本無法用於被毒氣殺死的兒童(或是一

出生就患有艾滋病的兒童、或是被「有限打擊」擊中的兒童)。哲學非但不能治癒牙疼,而且一個不斷嘮叨苦難的長期效益的人,可能還會引發頭疼。任何一位經歷

過愛人受抑鬱症折磨的人都知道,她病症背後的惡性怪圈意味着,抑鬱症本身就讓她聽不進邏輯,聽不進我們對她的再三寬慰;如果她能聽進去的話,她就不會受抑

鬱症的折磨了。

誠然,偶爾會有這種情況,我會遇到一個人(就把他當成我自

己吧),這個人一次次地重複同樣的錯誤,對朋友的話和常識漫不經心,他甚至不聽自己的話。於是他撞了車、或者心臟病發作了,忽然之間,災難能像警鐘那樣對

他起作用了;苦難打出的這一拳,不是更溫柔的手段所能替代的,苦難讓他警醒,促使他改變自己的行為方式。

偶爾也會有這種情況,我看到苦難可能僅存在於旁觀者的眼

中,那隻不過是我們無知的投影。四肢癱患者讓你不要對她表示同情;雖然她的痛苦比你的更顯而易見,但她很快活。印度加爾各答街頭或海地太子港街頭的人顛覆

了我們對惡劣環境與快樂和活力之間關係的認識,他問我們是不是把自己對貧窮的理解隨身帶來了?

然而,這能改變所有那種苦難嗎?那種苦難似乎未給我們帶來

一絲好處,只讓我們怨恨他人的勸告,那些人讓我們往好處想、讓我們數數遇到好運的時候,並記住時間能治癒所有創傷(其實我們知道它不能)。我們不指望生活

是容易的;約伯(Job)只想知道他為什麼始終顛沛流離。就像尼采(Nietzsche)和羅伯塔·弗蘭克(Roberta

Flack)所說的,生活就是受苦受難;生存就是搞清苦難的意義。

這是沒人能保證生存的原因。

或者,用18世紀的俳句大師小林一茶(Kobayashi

Issa)的話來說:「我知道這世界,如朝露般短暫。然而然而......」他在一首短詩里這樣寫道。儘管小林一茶以其恆久的肯定句而聞名,但他經歷了很

多死亡:兩歲時母親去世了,他的第一個兒子死了,他的父親感染上了傷寒,他的第二個兒子和另一個摯愛的女兒也死了。

他知道,苦難是人生不可避免的現實,他或許在自己的短詩里這樣說過;他知道,生命是短暫的,失去是這個世界上的法則。可是,當他一歲大的女兒感染天花死去時,他又如何能夠不期盼,不是那樣呢?

在他用詩表達了不情願的悲傷之後,他目睹了另一個兒子的死

亡,也看到自己身體的癱瘓。他的妻子生另一個孩子時死了,那個孩子也死了,也許是因為助產士的粗心大意。他再次結婚,但在幾周後就分居了。他第三次結婚,

他的房子被大火燒毀。最終,他的第三任妻子給他生下一個健康的女兒,可是小林一茶卻在64歲時離世,沒來得及看到自己小女兒的出生。

三年前,我高中時最親密的好友之一理乍得

(Richard)在得到前列腺癌的診斷後,創建了一個名為《這個朝露世界》(This world of

dew)的博客。我給他發了一些和小林一茶有關的信息。小林一茶的詩作,除了表達對生命之美的感激外,幾乎不涉及其他內容,直到他去世。可是理乍得很快就

在痛苦中死去,我最後一次見到他時,他幾乎不再能走動了。

我在日本的鄰居生活在這樣一種文化中,這種文化,在某個看

不見的層面,是建立在小林一茶所了解的佛教戒律之上的,那就是苦難既現實,儘管悲傷無需是我們對苦難的回應。這就是為什麼在我們看來日本人任勞任怨辛苦工

作、堅忍,並對苦難把人團結起來的各種方式有恆久認識的原因。英國人在倫敦大轟炸時也明白這點,其他文化在面對壓力時對此也不陌生。但是在一個建立在相互

依存觀念之上、一人所受之苦就是所有人所受之苦的態度之上的文化中,人們的這種認知加倍敏銳。

「我會盡全力!」、「我會堅持到底!」,以及「沒有辦

法」,這些是在日本的每小時你都能聽到的語句;兩年前的那場海嘯奪走了東京北部的數千條生命之後,我在加利福尼亞州聽到的悲嘆和恐慌,比我從京都附近的熟

人那裡聽到的要多。雖然我的鄰居們不是有條有理的哲學家,但是,在他們習慣的生命紋理中——全國上下一起祭拜隨秋葉而飄落的東西,櫻花燦爛綻放之後的迅速

凋謝,以及他們受到的類似小林一茶風格的詩詞教育——體現着一個古老文化的訓練有素,這種訓練讓他們學會告別事務,學會把喜悅和美麗置於一種框架之中。有

時,與求其永不到來的希望相比,死亡對我們的挫敗更小點。

還是孩子時,我學到一點小知識:「苦難」

(suffering)一詞的拉丁文(或許是希臘文)的字根是passion一詞的詞源(passion在英文中最常見的意思是「激情」,但在the

Passion of

Christ這個特定詞組中的意思是「受難」——譯註)。從詞源學的角度來說,和「苦難」相對應的是「冷漠」(apathy);可以說,耶穌受難

(the Passion of

Christ)是一個提醒,甚至是一個佐證,表明苦難是一些高尚的靈魂欣然接受的東西,為的是企圖減輕他人的痛苦。對他人苦難表達激情,就是「同情」

(compassion)。

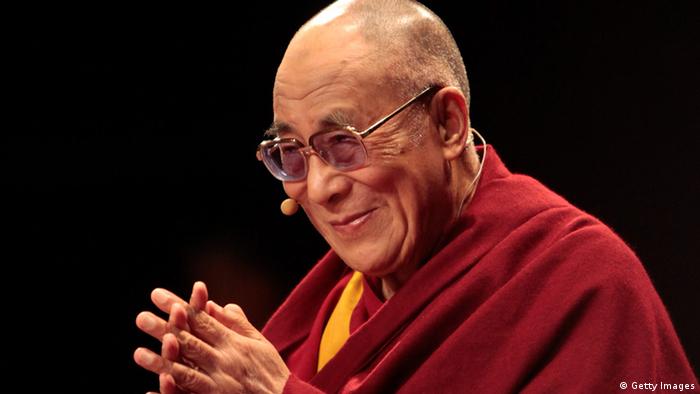

在日本海嘯發生近8個月後,我陪着達賴喇嘛來到小漁村石

卷,那個自然災難將漁村變成一片廢墟。墓碑即使沒有完全倒掉,也以亂七八糟的角度歪在那裡。一年前這裡還欣欣向榮,遍布着學校和家庭,而現在只剩下一堆破

磚爛瓦。三個剛從幼兒園升入小學的孤兒,穿着藍色校服,站在一座神奇地躲過大災難的寺廟外,歡迎達賴喇嘛的到來。在這棟木結構建築內的祭壇旁邊,放着十幾

個彩色的盒子,裡面裝着那些沒有倖存親屬認領的死者的骨灰,它們很整齊地排成一列,後面擺着鑲鏡框的照片,有老有少。

達賴喇嘛下車後,看到聚集在街上的數百名民眾,他們站在圍

繩後面,來歡迎他。他走過去,問他們現在過得怎麼樣。不少人失聲哭泣。「請改變心態,要有勇氣,」達賴喇嘛說到,便說邊擁抱一些人、給另外一些人祝福。

「請多幫助他人,加油挺過來;這是你能為逝去之人所能做的最好的事情。」然而,當他轉過身時,我看到他自己在抹眼淚。

然後他走進寺廟,向聚集在那裡坐在椅子上的人群講話。他

說,除了表示同情和前來看望,他不能指望給災民們任何其他的東西;一聽到發生了災難,他就知道自己必須到這兒來,即使他只能讓石卷的人們知道他們並不孤

單。達賴喇嘛繼續說道,對於石卷人正在感受的,他有點同感,因為當他還是一位23歲的年輕人時,一天下午,在他的老家拉薩,他被告知當晚必須離開家鄉,為

的是試圖阻止中國軍隊與他宮殿附近的藏人之間發生進一步的戰鬥。

他說,自己離開了朋友、家人,還有一隻小狗,而在接下來

52年中再也沒有回去過。離開拉薩兩天後,他聽說自己的朋友們死了。他嘗試過把失去變為機會,在流亡期間做了很多新東西,如果他留在舊西藏會很難那樣做;

他指出,對像他這樣的佛教徒而言,無法解釋的痛苦是因果報應的結果,有時是前世招致的罪孽,而對於那些信奉上帝的人來說,一切都是神的旨意。不過,他的眼

淚提醒我,我們仍活在小林一茶的「然而」世界之中。

這一大群日本人靜靜地聽着,然後,在其成員力所能及的情況

下,第二天他們開始重建家園。我想(雖然我不是佛教徒),比假設人們能戰勝苦難更糟糕的,就是想像在苦難來臨時無可作為。而我看到的眼淚讓我這樣想,你可

以足夠堅強去見證苦難,同時也可以具有足夠的人性而不假裝能夠駕馭苦難。有時,這些我們最不理解的東西,正是我們最應該信任的東西。這不就是愛和奇蹟所告

訴我們的嗎?

皮柯·耶爾(Pico Iyer)是查普曼大學(Chapman University)校長學術獎金獲得者。他最新出版的書是《我頭腦中的男人》(The Man Within My Head)。翻譯:張薇、谷菁璐Opinion

The Value of Suffering

September 12, 2013

NARA, Japan — Hundreds of Syrians are apparently

killed by chemical weapons, and the attempt to protect others from that

fate threatens to kill many more. A child perishes with her mother in a

tornado in Oklahoma, the month after an 8-year-old is slain by a bomb in

Boston. Runaway trains claim dozens of lives in otherwise placid Canada

and Spain. At least 46 people are killed in a string of coordinated

bombings aimed at an ice cream shop, bus station and famous restaurant

in Baghdad. Does the torrent of suffering ever abate — and can one

possibly find any point in suffering?

Wise men in every tradition

tell us that suffering brings clarity, illumination; for the Buddha,

suffering is the first rule of life, and insofar as some of it arises

from our own wrongheadedness — our cherishing of self — we have the cure

for it within. Thus in certain cases, suffering may be an effect, as

well as a cause, of taking ourselves too seriously. I once met a

Zen-trained painter in Japan, in his 90s, who told me that suffering is a

privilege, it moves us toward thinking about essential things and

shakes us out of shortsighted complacency; when he was a boy, he said,

it was believed you should pay for suffering, it proves such a hidden

blessing.

Yet none of that begins to

apply to a child gassed to death (or born with AIDS or hit by a “limited

strike”). Philosophy cannot cure a toothache, and the person who starts

going on about its long-term benefits may induce a headache, too.

Anyone who’s been close to a loved one suffering from depression knows

that the vicious cycle behind her condition means that, by definition,

she can’t hear the logic or reassurances we extend to her; if she could,

she wouldn’t be suffering from depression.

Occasionally, it’s true,

I’ll meet someone — call him myself — who makes the same mistake again

and again, heedless of what friends and sense tell him, unable even to

listen to himself. Then he crashes his car, or suffers a heart attack,

and suddenly calamity works on him like an alarm clock; by packing a

punch that no gentler means can summon, suffering breaks him open and

moves him to change his ways.

Occasionally, too, I’ll see

that suffering can be in the eye of the beholder, our ignorant

projection. The quadriplegic asks you not to extend sympathy to her;

she’s happy, even if her form of pain is more visible than yours. The

man on the street in Calcutta, India, or Port-au-Prince, Haiti,

overturns all our simple notions about the relation of terrible

conditions to cheerfulness and energy and asks whether we haven’t just

brought our ideas of poverty with us.

But does that change all

the many times when suffering leaves us with no seeming benefit at all,

and only a resentment of those who tell us to look on the bright side

and count our blessings and recall that time heals all wounds (when we

know it doesn’t)? None of us expects life to be easy; Job merely wants

an explanation for his constant unease. To live, as Nietzsche (and

Roberta Flack) had it, is to suffer; to survive is to make sense of the

suffering.

That’s why survival is never guaranteed.

OR put it as Kobayashi

Issa, a haiku master in the 18th century, did: “This world of dew is a

world of dew,” he wrote in a short poem. “And yet, and yet. ...” Known

for his words of constant affirmation, Issa had seen his mother die when

he was 2, his first son die, his father contract typhoid fever, his

next son and a beloved daughter die.

He knew that suffering was a

fact of life, he might have been saying in his short verse; he knew

that impermanence is our home and loss the law of the world. But how

could he not wish, when his 1-year-old daughter contracted smallpox, and

expired, that it be otherwise?

After his poem of reluctant

grief, Issa saw another son die and his own body paralyzed. His wife

died, giving birth to another child, and that child died, maybe because

of a careless nurse. He married again and was separated within weeks. He

married a third time and his house was destroyed by fire. Finally, his

third wife bore him a healthy daughter — but Issa himself died, at 64,

before he could see the little girl born.

My friend Richard, one of

my closest pals in high school, upon receiving a diagnosis of prostate

cancer three years ago, created a blog called “This world of dew.” I

sent him some information about Issa — whose poems, till his death,

express almost nothing but gratitude for the beauties of life — but

Richard died quickly and in pain, barely able to walk the last time I

saw him.

MY neighbors in Japan live

in a culture that is based, at some invisible level, on the Buddhist

precepts that Issa knew: that suffering is reality, even if unhappiness

need not be our response to it. This makes for what comes across to us

as uncomplaining hard work, stoicism and a constant sense of the ways

difficulty binds us together — as Britain knew during the blitz, and

other cultures at moments of stress, though doubly acute in a culture

based on the idea of interdependence, whereby the suffering of one is

the suffering of everyone.

“I’ll do my best!” and

“I’ll stick it out!” and “It can’t be helped” are the phrases you hear

every hour in Japan; when a tsunami claimed thousands of lives north of

Tokyo two years ago, I heard much more lamentation and panic in

California than among the people I know around Kyoto. My neighbors

aren’t formal philosophers, but much in the texture of the lives they’re

used to — the national worship of things falling away in autumn, the

blaze of cherry blossoms followed by their very quick departure, the

Issa-like poems on which they’re schooled — speaks for an old culture’s

training in saying goodbye to things and putting delight and beauty

within a frame. Death undoes us less, sometimes, than the hope that it

will never come.

As a boy, I’d learned that

it’s the Latin, and maybe a Greek, word for “suffering” that gives rise

to our word “passion.” Etymologically, the opposite of “suffering” is,

therefore, “apathy”; the Passion of the Christ, say, is a reminder, even

a proof, that suffering is something that a few high souls embrace to

try to lessen the pains of others. Passion with the plight of others

makes for “compassion.”

Almost eight months after

the Japanese tsunami, I accompanied the Dalai Lama to a fishing village,

Ishinomaki, that had been laid waste by the natural disaster.

Gravestones lay tilted at crazy angles when they had not collapsed

altogether. What once, a year before, had been a thriving network of

schools and homes was now just rubble. Three orphans barely out of

kindergarten stood in their blue school uniforms to greet him, outside

of a temple that had miraculously survived the catastrophe. Inside the

wooden building, by its altar, were dozens of colored boxes containing

the remains of those who had no surviving relatives to claim them, all

lined up perfectly in a row, behind framed photographs, of young and

old.

As the Dalai Lama got out

of his car, he saw hundreds of citizens who had gathered on the street,

behind ropes, to greet him. He went over and asked them how they were

doing. Many collapsed into sobs. “Please change your hearts, be brave,”

he said, while holding some and blessing others. “Please help everyone

else and work hard; that is the best offering you can make to the dead.”

When he turned round, however, I saw him brush away a tear himself.

Then he went into the

temple and spoke to the crowds assembled on seats there. He couldn’t

hope to give them anything other than his sympathy and presence, he

said; as soon as he heard about the disaster, he knew he had to come

here, if only to remind the people of Ishinomaki that they were not

alone. He could understand a little of what they were feeling, he went

on, because he, as a young man of 23 in his home in Lhasa had been told,

one afternoon, to leave his homeland that evening, to try to prevent

further fighting between Chinese troops and Tibetans around his palace.

He left his friends, his

home, even one small dog, he said, and had never in 52 years been back.

Two days after his departure, he heard that his friends were dead. He

had tried to see loss as opportunity and to make many innovations in

exile that would have been harder had he still been in old Tibet; for

Buddhists like himself, he pointed out, inexplicable pains are the

result of karma, sometimes incurred in previous lives, and for those who

believe in God, everything is divinely ordained. And yet, his tear

reminded me, we still live in Issa’s world of “And yet.”

The large Japanese audience

listened silently and then turned, insofar as its members were able, to

putting things back together again the next day. The only thing worse

than assuming you could get the better of suffering, I began to think

(though I’m no Buddhist), is imagining you could do nothing in its wake.

And the tear I’d witnessed made me think that you could be strong

enough to witness suffering, and yet human enough not to pretend to be

master of it. Sometimes it’s those things we least understand that

deserve our deepest trust. Isn’t that what love and wonder tell us, too?

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/jun/15/man-within-my-head-pico-iyer-review

中国でチベット族に警察発砲 ダライ・ラマの誕生日

【広州=小山謙太郎】中国四川省のカンゼ・チベット族自治州タウ県で6日、インドに亡命中のチベット仏教最高指導者ダライ・ラマ14世(78)の誕生日を祝おうと集まったチベット族僧侶や住民に武装警察が発砲し、少なくとも7人が負傷したと、米政府系の放送局ラジオ・フリー・アジアなどが10日までに伝えた。 1人が頭部を撃たれ、重体という。住民ら数百人は同県にある聖山に登ろうとしていたが、武装警察は催涙弾も撃って阻んだという。銃撃が実弾かは不明。

新聞報導

達賴喇嘛接受日媒採訪

藏人精神領袖達賴喇嘛對媒體說,"使用秘密、新聞管制以及打壓異議聲音"的手段,在中國必須停止。他說,即將上任的中國國家主席習近平"沒有選擇",他只能接受未來數年政治上發生的變化。

(德國之聲中文網)目前,達賴喇嘛正在日本進行為期12天的訪問。週一,他在橫濱市對媒體說,"胡錦濤開始建設和諧社會,穩定的社會。而一個穩定的社會,我想貧富之間的差距必須降低。"此外,中國"還需要獨立的司法制度,言論自由以及法治。這些都是非常非常重要的。""因此,和諧與穩定都是美妙的目標。但使用秘密手段,新聞管制以及打壓異議聲音,說明製度中有錯誤的東西。""我想,構建真正的和諧,你必須開放。"

達賴喇嘛在日本擁有大批信眾,他也經常訪問這個國家。這位現年77歲的諾貝爾和平獎得主說,他相信民主是中國能夠接受並解決問題的最好制度,包括化解同日本的領土主權爭議。他說,過分強調民族主義是產生分歧的根源之一。達賴喇嘛說,中國使用的教材"很極端,都好像在說中國的文化是最偉大的,中華民族是最偉大的。"他還說,"過多渲染情緒,就會不現實,不理智。"

達賴喇嘛說,由於缺乏資訊,中國許多人仍然將日本人同軍國主義連在一起。他說,這也導致在日本將尖閣列島部分島嶼(中國稱釣魚島)國有化後,中國的反日情緒爆發,一些商店被搶被燒。

在問到北京和東京怎樣才能擱置爭議時,達賴喇嘛說,"基本上我想,中國需要日本,日本也需要中國……應該更全盤地來思索。一些小的爭議不應發展成大的衝突。思路要更寬一些。"

來源:法新社編譯:李魚

| 媒体看中国 |

|

| 流亡藏人近日在达兰萨拉举行会议,磋商未来对中国战略。 |

|

(法新社)达赖喇嘛表示,

1954年,达赖喇嘛在北京

1954年,达赖喇嘛在北京《中英對照讀新聞》China collecting Dalai Lama blood samples:Tibet exiles 西藏流亡人士︰中國蒐集達賴喇嘛的血液樣本

Chinese agencies are secretly collecting samples of the Dalai Lama’s blood, urine and hair and are stepping up efforts to harm him, the Tibetan government in exile said.

中國機構正秘密蒐集達賴喇嘛的血液、尿液與毛髮樣本,同時加緊努力要傷害他,西藏流亡政府指出。

Citing "a variety of threats" to the spiritual leader’s life, the KASHAG or cabinet of the government in exile accused China of "making concrete plans to harm His Holiness by employing well-trained agents, particularly females".

「噶廈」亦即西藏流亡政府內閣,援引對這位精神領袖生命的「多種威脅」,指控中國「制定具體計畫,利用訓練有素的特務,尤其是女性來傷害尊者」。

"Chinese intelligence agencies have stepped up their efforts to collect intelligence on the status of His Holiness’s health, as well as collecting physical samples of his blood, urine and hair," it said in a statement.

「中國情報機關已加緊努力蒐集尊者的健康狀態,及其血、尿與毛髮的身體樣本,」該單位聲明指出。

"It is also learnt that they are exploring the possibility of harming him by using ultra-modern and highly sophisticated drugs and poisonous chemicals." Dongchung Ngodup, minister of security in the cabinet told AFP the government was informed about these threats by sources inside Tibet.

「我們也得知他們利用超現代與高度複雜的藥物及有毒化學物質,探索傷害他的可能性。」內閣安全部長忠群額珠告訴法新社說,西藏內部的消息來源告知當局有關這些威脅。

Earlier this month the Dalai Lama told Britain’s Sunday Telegraph newspaper that he had been informed of a plot to assassinate him, using Tibetan women posing as devotees seeking his blessing.

本月初,達賴喇嘛告訴英國週日電訊報,他被知會刺殺他的陰謀,該計謀利用藏族女性喬裝成尋求他祝福的虔誠信徒。

In the interview, the Dalai Lama said he was told the Tibetan women would be wearing poisonous scarves and have poisonous hair. "They were supposed to seek blessing from me, and my hand touch," he said. But he added that there was "no possibility to cross-check, so I don’t know". (AFP)

在專訪中,達賴喇嘛說,他被告知這些藏族婦女將圍著有毒的哈達,同時有著一頭毒髮。「她們理當尋求我的祝福以及我的手觸摸,」他說。不過他補充,「沒有多方查證的可能性,所以真偽我不知道。」(法新社)

新聞辭典

step up︰片語,加快、增加。例句︰"Step it up a little more," he said to the driver.(「請再快點,」他對司機說。)

well-trained︰形容詞,訓練有素的。例句︰She is a well-trained nanny.(她是受過良好訓練的保母。)

cross-check︰動詞或名詞,多方核實。例句︰We must cross-check the data.(我們必須查核這個數據。)

BBC

西藏流亡精神領袖達賴喇嘛在印度達蘭薩拉接受台灣媒體采訪時表示,鑒于台灣與中國的關系正趨于和緩,希望明年第三度訪問台灣。

達賴喇嘛在接受台灣《愛爾達》頻道專訪時表示,“台灣與中國間的關系正往和緩方向發展,此刻或許是訪問台灣的好時機。”

達賴喇嘛還說,“我已多年未再造訪台灣,但我并未忘記台灣!”

此前,達賴喇嘛也記者們做過類似的表示。他表示,“為了跟華人兄弟姊妹建立友好關系,以及為了佛法交流能使更多信教同修探討佛法,如果未來有機會,非常樂意再次前往台灣訪問。”

1997、2001年,達賴喇嘛曾經兩度訪問台灣,并會見了當時的台灣總統李登輝和陳水扁。如今,他再次表達訪台意愿,分析人士說,一旦成行,很可能對台灣現任總統馬英九的大陸政策形成沖擊。

據路透社報道,西藏流亡政府議員凱度頓珠在台灣表示,達賴喇嘛在台灣有很多朋友,這些朋友都在等待他再來訪問。凱度頓珠也非常希望除了北京,沒有其它方面反對達賴的訪問。

中國剛剛因為法國總統薩爾科齊即將同達賴見面而推遲了例行的中國歐盟峰會。

流亡藏人近日在达兰萨拉举行会议,磋商未来对中国战略。这是达赖喇嘛辞去政治职务以来流亡藏人的最大规模会议。《南德意志报》指出,鉴于同北京的和平对话毫无进展,年轻一代藏人对非暴力抗争的意义越来越持怀疑态度。

(德国之声中文网)《南德意志报》写道:

“洛桑森格(Lobsang Sangay)知道寄托在他身上的、现在还无法满足的那种希望。中国在西藏问题上毫厘未动。洛桑森格是流亡藏人的噶伦赤巴(Kalon Tripa),相当于政府总理。去年,达赖喇嘛大大增加了这一职务的份量,并以自己未来将只从事宗教事务的表态使追随者大吃一惊。在流亡藏人社区历史上首 次民主选举了政治领袖,胜出的是洛桑森格。他在境外出生,还从未去过西藏。......担任了一年的噶伦赤巴后,他尚未极度绝望,虽然在同北京的政治较量 中他还拿不出任何可以量度的成绩。......尽管在最重要的问题上迄无进展,在达兰萨拉的医院、市场、饭馆里,流亡藏人们依然赞扬这位总理的勤勉、努力 和改革意愿。与此同时,噶伦赤巴因其所持的温和立场受到批评。而这一立场正是他从达赖喇嘛那里继承下来的:在中国框架内争取更多西藏自主权,仅此而已。”

《南德意志报》指出,在年轻一代的流亡藏人中间,已出现对这一温和立场越来越多的怀疑,甚至不满:

《南德意志报》指出,在年轻一代的流亡藏人中间,已出现对这一温和立场越来越多的怀疑,甚至不满:

“对西藏青年大会主席次旺仁增(Tsewang Rigzin)而言,这一立场过于温和。......他的办公室距位于达兰萨拉谷底的噶伦赤巴官邸不过数公里,但在观点上,两人之间则明显不同。这位西藏 最大流亡组织的负责人表示,‘如果藏人要在这个星球上存活,独立于中国是唯一的解决办法’。......次旺仁增指出,不断增加的(藏人)自焚数字是绝望 的反应,这一绝望情绪在西藏年轻一代中日益普遍。西藏青年大会明确反对自焚,但‘这种为自由西藏而战的斗争中所作出的最大牺牲对我们是一种激励’。现年 41岁的次旺仁增表示,为西藏进行非暴力抗争是达赖喇嘛提出的要求,他的支持者遵从这一要求。但‘未来会是何种路线,现在还无法预计’。”

中国首艘航母本周正式交付海军入役,引起外界对中国大力增强武装力量的强烈关注。

中国首艘航母本周正式交付海军入役,引起外界对中国大力增强武装力量的强烈关注。

国力大增的后果?

《明星》周刊就中日岛屿主权之争新近加剧指出,中日争执并非孤立现象,而是中国经济成功、国力增强的后果之一,可以解释中国何以也同其他周边国家发生主权争议:

“依靠其经济力量,中国在亚洲也实施起一种帝国主义的战略。他的外汇储备增加到了3.2万亿美元。中国将昔日的强国日本排挤到第三经济大国的位置,并成为 地区各国最重要的贸易伙伴。......(不过)北京知道,有些问题是无法用金钱和礼物解决的。为对付这些问题,人民解放军在过去数年里进行了彻底的现代 化改造和装备。它未来应能在全球范围内投入战斗,该国军队规模为220万人。”

摘编:凝炼

责编:叶宣

[摘编自其它媒体,不代表德国之声观点]

“洛桑森格(Lobsang Sangay)知道寄托在他身上的、现在还无法满足的那种希望。中国在西藏问题上毫厘未动。洛桑森格是流亡藏人的噶伦赤巴(Kalon Tripa),相当于政府总理。去年,达赖喇嘛大大增加了这一职务的份量,并以自己未来将只从事宗教事务的表态使追随者大吃一惊。在流亡藏人社区历史上首 次民主选举了政治领袖,胜出的是洛桑森格。他在境外出生,还从未去过西藏。......担任了一年的噶伦赤巴后,他尚未极度绝望,虽然在同北京的政治较量 中他还拿不出任何可以量度的成绩。......尽管在最重要的问题上迄无进展,在达兰萨拉的医院、市场、饭馆里,流亡藏人们依然赞扬这位总理的勤勉、努力 和改革意愿。与此同时,噶伦赤巴因其所持的温和立场受到批评。而这一立场正是他从达赖喇嘛那里继承下来的:在中国框架内争取更多西藏自主权,仅此而已。”

“对西藏青年大会主席次旺仁增(Tsewang Rigzin)而言,这一立场过于温和。......他的办公室距位于达兰萨拉谷底的噶伦赤巴官邸不过数公里,但在观点上,两人之间则明显不同。这位西藏 最大流亡组织的负责人表示,‘如果藏人要在这个星球上存活,独立于中国是唯一的解决办法’。......次旺仁增指出,不断增加的(藏人)自焚数字是绝望 的反应,这一绝望情绪在西藏年轻一代中日益普遍。西藏青年大会明确反对自焚,但‘这种为自由西藏而战的斗争中所作出的最大牺牲对我们是一种激励’。现年 41岁的次旺仁增表示,为西藏进行非暴力抗争是达赖喇嘛提出的要求,他的支持者遵从这一要求。但‘未来会是何种路线,现在还无法预计’。”

中国首艘航母本周正式交付海军入役,引起外界对中国大力增强武装力量的强烈关注。

中国首艘航母本周正式交付海军入役,引起外界对中国大力增强武装力量的强烈关注。《明星》周刊就中日岛屿主权之争新近加剧指出,中日争执并非孤立现象,而是中国经济成功、国力增强的后果之一,可以解释中国何以也同其他周边国家发生主权争议:

“依靠其经济力量,中国在亚洲也实施起一种帝国主义的战略。他的外汇储备增加到了3.2万亿美元。中国将昔日的强国日本排挤到第三经济大国的位置,并成为 地区各国最重要的贸易伙伴。......(不过)北京知道,有些问题是无法用金钱和礼物解决的。为对付这些问题,人民解放军在过去数年里进行了彻底的现代 化改造和装备。它未来应能在全球范围内投入战斗,该国军队规模为220万人。”

摘编:凝炼

责编:叶宣

[摘编自其它媒体,不代表德国之声观点]

沒有留言:

張貼留言