Nathan Silver, Who Chronicled a Vanished New York, Dies at 89

An architect, he wrote in his book “Lost New York” about the many buildings that were destroyed before passage of the city’s landmarks preservation law.Editors’ Picks

Go Ahead, Have a ‘Fridge Cigarette’

27 No-Cook Recipes for a Heat Wave

Can Menopause Be Funny?

Image

“While cities must adapt if they are to remain responsive to the needs and wishes of their inhabitants, they need not change in a heedless and suicidal fashion,” Mr. Silver wrote in his book “Lost New York.”Weathervane

“While cities must adapt if they are to remain responsive to the needs and wishes of their inhabitants, they need not change in a heedless and suicidal fashion,” Mr. Silver wrote in his book “Lost New York.”Weathervane“Lost New York,” which Mr. Silver said sold more than 100,000 copies, was a finalist for the National Book Award in history and biography in 1968.

In 2014, when Mr. Silver made a rare trip to New York City, David Dunlap of The New York Times wrote that Mr. Silver believed landmarks “were vessels of human history,” adding, “How a building was used, and by whom, were almost as important to him as what the structure looked like.”

\\\杜邦防彈纖維之母過世 享年90歲

傅莞淇 2014年06月23日 17:40

Hao-Hsiu Chiu 新增了 2 張相片。

夜讀Cedric Price,這位幾乎無實際作品,卻在70年代以Fun Palace、Thinkbelt等紙上建築提案對於「日常」(ordinary)的關注,影響了Archigram、Rogers、Foster甚至後起的Koolhaas。本屆威尼斯雙年展瑞士館策展人Hans Ulrich Obrist再次審視Price的空間社會學立論,希望「明日學院」的各個參與團隊,回應這個西方開始偏離現代主義思維的Fundamental,對於東海建築這個東方團隊,可真是個挑戰。

----簡介 英文

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GPjlH0DEsXE

Cedric Price

Hugely creative architect ahead of his time in promoting themes of lifelong learning and brownfield regeneration

One of architecture's apparent paradoxes is that some of its most influential thinkers build very few buildings. Cedric Price, who has died aged 68, completed relatively little and never ran a large office, but his influence - through drawings, proposals, teaching and conversation - remains enormous.

It can be traced in the work of Richard Rogers and Norman Foster, Archigram (the winners of the 2002 Royal Institute of British Architects' gold medal) and even in the eastward expansion of London in the Thames Gateway. His interests anticipated the now fashionable themes of lifelong learning and brownfield regeneration.

From his 1960s designs for such structures as Joan Littlewood's Fun Palace, the Potteries Thinkbelt and Nonplan, up to and beyond Magnet in 1997, Price explored architecture's potential to nurture change, intellectual growth and social development rather than to offer a definitive aesthetic statement.

As someone particularly interested in lightweight structures and the idea that buildings should have a fixed, often short, life, it was inevitable that he would build little during a period when buildings have increasingly been seen as solid, long lasting investments. By its very nature, his work was elusive, enticing and open-ended.

Price was born in Stone, Staffordshire, the son of the architect AJ Price, who worked on some of the great cinemas of that decade. Though he died in 1953, before his son went up to St John's College, Cambridge, to read architecture, Cedric was proud of his achievements, and delighted in referring to his technical manuals, latterly at least, as much for their value as social documents as for the quality of their advice.

In 1959, while completing his studies at the Architectural Association in London, he encountered the brilliant urban theorist Arthur Korn, an Austrian émigré whose work showed how Price's interests in indeterminacy, and suspicion of formality and convention, might contribute to remaking the built environment and the social relationships it embodied.

The following year, Price established Cedric Price Architects, and soon began producing a series of unrealised projects that catapulted him to international fame. In the Fun Palace (1961) and Potteries Thinkbelt (1964), both designed to offer innovative learning and leisure opportunities, he used architecture as the catalyst to redefine the standard relationships between people and institutions. Both were essentially short-term, fixed-life structures and enclosures giving opportunities for education, delight and fulfilment in deprived areas of east London and the pottery towns.

The architecture was indeterminate, flexible and driven by what technology then existed - and some that Price anticipated - for exchanging ideas and goods, and the movement of people from place to place. Their aesthetic of frames and gantries derived from familiar industrial architecture, rather than from the forbidding monuments of public architecture. Above all, Price and Littlewood offered a focus to the optimism of the time, when it seemed possible to remake society around the potential for delight and opportunity.

While the Interaction Centre, built in London's Kentish Town in 1971, put some of these ideas into practice on a reduced scale, Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers's Pompidou Centre would have been inconceivable without the Fun Palace.

Delight was extremely important to Price, and it gave a twist to his socialist views. Anyone prepared to treat the achievement of delight seriously was a potential friend, whether it was the flamboyant Labour MP Tom Driberg, the former Tory party treasurer Alastair MacAlpine, Princess Margaret and Lord Snowdon, with whom Price and the engineer Frank Newby designed the aviary at London Zoo, or the architect David Allford, whose most famous building was Gatwick airport.

But there was always a political element to Price's work. As he wrote of the Potteries Thinkbelt: "Education, if it is to be a continuous human service run by the community must be provided with the same lack of peculiarity as the supply of drinking water or free teeth." Architecture might help to achieve that aim by uncovering and connecting latent desires.

Nonplan, produced in 1969 with the planner Sir Peter Hall and Paul Barker, of New Society magazine, challenged the established orthodoxy of planning around established uses of land. Consistent with his belief in Pop-up Parliament, a project of 1965, Price argued that unnecessary legislation was a break on social development; planning, he believed, should switch from being "curative to preventative", setting limits rather than being didactic. It lies behind much of Hall's thinking in his contribution to the Thames Gateway.

More recent projects brought these themes to specific urban contexts. A proposal for a large site on Manhattan's west side suggested making a "lung" for the city, weaving between buildings and infrastructure. "Ducklands" looked at ways of turning redundant docks in Hamburg into bird sanctuaries, and Magnet, shown at the Architecture Foundation, proposed a series of 10 reusable structures, offering "safety, access, information, view and sanctuary" in London locations chosen for their typical urban condition of major roads, railway cuttings, parks and shopping streets.

A combination of iconoclasm and mental fecundity kept Price at the forefront of architectural debate, enthusing new generations of students and architects as he had once impressed his elders at the Cambridge Society of Arts. His ways of thinking about issues we have not yet satisfactorily resolved still resonate.

He is survived by his partner, the actor Eleanor Bron.

· Cedric John Price, architect, born September 11 1934; died August 10 2003

---mages

- Cedric Price

CEDRIC PRICE & THE FUN PALACE

’Now! Now!’ cried the Queen. ‘Faster! Faster!’ … Alice looked round her in great surprise. ‘Why, I do believe we’ve been under this tree the whole time! Everything’s just as it was!’

‘Of course it is’, said the Queen. “What would you have it?’

‘Well, in our country,’ said Alice, still panting a little, ‘you’d generally get to somewhere else – if you ran very fast for a long time, as we’ve been doing.’

‘A slow sort of country!’ said the Queen. ‘Now, HERE, you see, it takes all the running YOU can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!’

‘Of course it is’, said the Queen. “What would you have it?’

‘Well, in our country,’ said Alice, still panting a little, ‘you’d generally get to somewhere else – if you ran very fast for a long time, as we’ve been doing.’

‘A slow sort of country!’ said the Queen. ‘Now, HERE, you see, it takes all the running YOU can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!’

Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking Glass

The notion of an architecture of movement has always remained problematic given the immobility of typical built environments. And yet, Cedric Price, a British architect, not only theorized that movement was integral to architecture but he reflected this in his architectural practice. From the 1960s and into the early 1970s, his visionary thinking contributed to the development of new philosophies about architecture, time, and space and within the city. It was also during this period that many younger architects saw the need for a radicalization of architecture. They began to envision a built form that was no longer merely static, but instead comprised of spaces in time that both informed and were informed by the complex social, economic and cultural changes of dynamic societies. This view also contributed to a shift in the thinking of the ‘city’ as well. It was no longer conceived as a cohesive structure but instead as an unstable series of systems, in continual transformation, constantly reorganizing and rearranging itself through processes of both expansion and retraction.

Price espoused that time was a critical yet forgotten component of architecture. Reference to movement by necessity is a reference to time. These concepts inform each other and receive expression in discussion of speed. For a building to be in constant motion it would be difficult to locate and define (on paper), because its position would be changing at the moment of its (false) definition. Price believed that this motion could be defined because we already have a ‘questionable’ language for describing speed and movement in general terms. Cedric Price in clarifying these concepts stated in an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist that “movement implies a measurable interval, always in time and frequently in distance… mobility describes the capacity for movement.”

According to Price, time played two important roles in architecture, the potential needs of the built form must be recognised, but since an architect cannot accurately predict the uses and changes over time, the architect must “acknowledge the impossibility of totalised planning, and build in a degree of indeterminacy to allow for uncertainties in program, obsolescence and complete changes of use throughout the life of the building.” However, Price also recognised that if a building has outlive its usefulness, regardless of how well it anticipated the uncertainties, at that point it should be dismantled not retrofitted.

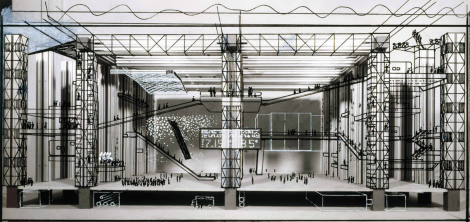

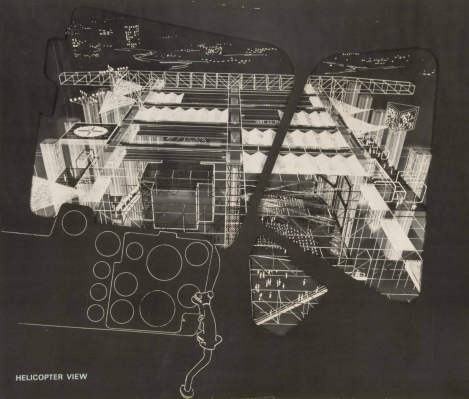

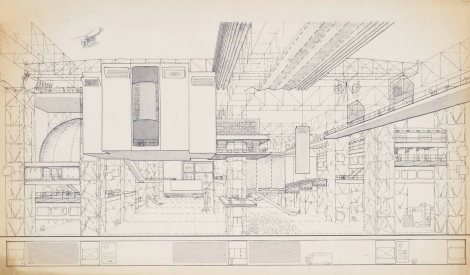

The Fun Palace was conceived by Cedric Price and Theater Director Joan Littlewood as a laboratory of fun and a university of the streets that was not driven by an economic agenda. It was to be located in the Lea Valley in London’s city core. The initial source of inspiration was to re-invent the 18th century Vauxhall Gardens under an all-weather roof. The attraction to the Vauxhall Garden was it encompassing of different social classes, where patrons enjoyed music, lights, fireworks, walking, and the gardens in an open-air atmosphere. They saw this project as an attempt to deviate from the accepted notion of a conformed environment because the individual was in control of their own “self-participation” in creating their own “physical environment.”[1] Price acknowledged that while the activities offered by Fun Palace were already available to the public, it was the ‘inter-accessibility’ of the activities and their juxtaposition to each other that would allow for the creation of new activities and experiences.

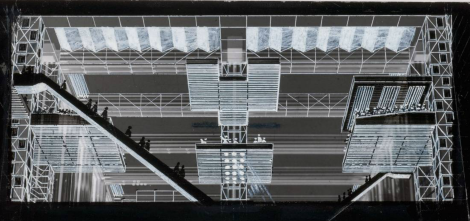

The configuration of Fun Palace was similar to a basilica with a central nave and two aisles, replacing the transept “was a moving gantry crane spanning over a system of 5 rows by 15 steel columns … The central nave [would] host the mass activities (movies, theatre and rallies) while the side aisles [would] hold “the human servicing activities” such as restaurants, bars, children areas and workshops … The adjustable sky blinds protect the palace-goers from the rain while vapor and warm air barriers eliminate the need of external walls. The resulting space modifies its shape through temporary and variable barriers: fiber panels, optical barriers, pressed aluminum curtains, audio-phonic curtains and curtains made of quilted lead foil.”[2]Also included in the plans was a high-level suspension grid, that would be the only fixed component of the structure, everything else was capable of movement. Decks and elevators would provide pedestrian movement throughout the complex. The plans deliberately did not include an entranceway which allowed individuals to walk freely without the interference of a prescribed pathway.

[1] Price, Cedric, “The Fun Palace” Cedric Price, Architectural Association works 2, Architectural Association, London, 1984. pg. 60.[2] Mongelli, Nicola, “The Fun Palace, A Curtain That Never Rose”,http://www.mongelli2000.com/nicola/xresearch.html, 2000

I thought I would highlight this apartment in Hong Kong, designed by Gary Chang an architect, which transforms into 24 different designs all by sliding panels and wall a process that Price envisioned for Fun Palace.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HV_5wwqyJiw

沒有留言:

張貼留言